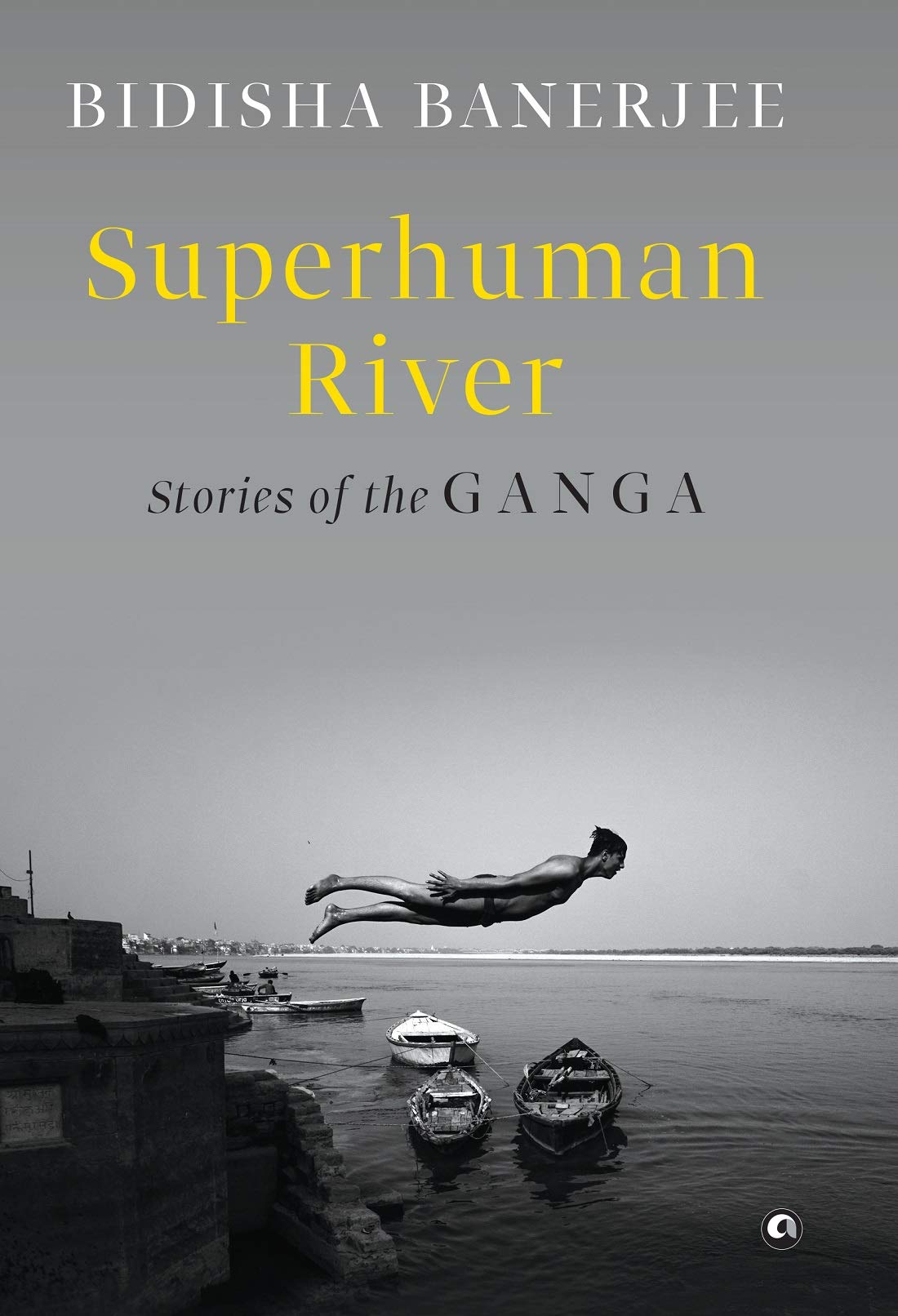

BOOK: Superhuman River: Stories of the Ganga by Bidisha Banerjee

AUTHOR: Bidisha Banerjee

PUBLISHER: Aleph

PRICE: Rs 499

Superhuman River: Stories of the Ganga by Bidisha Banerjee is a deeply personal account of her experiences with India’s national river. She keeps returning to the concept of Gangahriday — the Ganga-hearted — which implies both the ancient territory of southern Bengal and the idea that the Ganga exists within the soul of all Indians and to which they feel a spiritual, umbilical pull; it is after all their pehchaan. Indeed, two things drive Banerjee to pen this book in the first place — her childhood memory of splashing about in a bucket and imagining the bathwater as the Ganga itself and the sharp dissonance she felt on learning that the river could dry up and disappear imminently.

Written as part travelogue, Superhuman River enmeshes myths, religious fervour, history, geography, politics and ecologies surrounding the Ganga. These are not presented in isolation, within delineated chapters, but merged together in a lucid narrative, allowing a deeper understanding of the existing societal and riverine links along the lifeblood of the Indian subcontinent. The different points of Banerjee’s journey downstream from the river’s source become the settings for investigating larger questions about the river’s meaning, ownership and sustainability. The titular ‘Superhuman’ denotes both the Ganga — which the author contends must have powers far greater than that of mere mortals in being able to sustain such teeming millions in spite of the pressures exerted on it — and also the human race — which, in the Anthropocene, has the ability to decisively alter any natural process through technological implements and environmental excesses.

Banerjee’s writing is candid and creates landscapes that are easily envisioned. Her thoughts are expressed with clarity and humour, be it the uplifting taste of fresh glacial melt at Gomukh or the lingering queasiness after a sip of Gangajal from its polluted Kanpur stretch. The concept of penance through pilgrimage and the deeply imbedded Indian belief that the Ganga shall self-sustain through all ills are examined deftly. Feelings of communion and community lace her accounts of the Kumbh at Allahabad and of watching a total solar eclipse alongside the thousands thronging the ghats of Varanasi. She also sharply underlines the fallacies in the National Mission for Clean Ganga plans and the general apathy to tackling pollution, be it the inaction over the chromium contamination around Kanpur or the Uttar Pradesh government machinery effectively mobilizing to conduct a successful Kumbh Mela but doing little to ensure reduced pollution levels in the Ganga.

Superhuman River: Stories of the Ganga by Bidisha Banerjee, Aleph, Rs 499. Amazon

Crossing over into Bihar, Banerjee recounts her visit to the Vikramshila Gangetic Dolphin Sanctuary near Bhagalpur and a sense of wonderment is evident in her sighting of the endangered Ganges River Dolphin (shushuk) — India’s national aquatic animal. The almost pristine riverscape and tales of myriad creatures in their natural habitats lends this chapter a refreshing, idyllic feel. Yet, as she succinctly documents, the failure of societal governance measures in the aftermath of the Ganga Mukti Andolan undertaken by the local community of fishermen against a feudal water tax in the 1980s has given rise to the mafia who control the monsoon inundated diaras and the adjacent riparian tracts. Their exploitative practices and the ineptness of the local administration have further sharpened the man-animal conflict within the sanctuary, and can push the shushuk further towards extinction.

A cartographic disagreement spurs Banerjee’s visit to Bangladesh. This invokes ancestral reconnections; Banerjee also sees through the “post-Partition amnesia” that has engulfed West Bengal and Bangladesh — both residents of the Ganga-Padma delta but divided by imposed borders and disagreements over river-diversion projects like the Farakka Barrage, which has done much harm on both sides. Back across the border, at Gaur, Banerjee shows how the river’s changing meanders have altered history’s course — birthing, enabling and desolating settlements and civilizations. Her journeys end first at Sagar Island where the Ganga indistinguishably merges with the sea and then at Satjelia Island in the Sundarbans, where, regaled by tales of Bonbibi and Dokkhin Rai, she highlights how different communities must reach a consensus on a shared, sustainable use of the Commons, freeing the river from the yoke of the large-scale public works that encumber it. This is prescient given the likely environmental effects that the National Waterways Act will have on the Ganga by morphing it into a mere conduit for barges by repeated dredging.

Distinct from a travel book and containing more than just historical accounts, Superhuman River continues a familial trend of writing about the Ganga — the author’s grandfather, Manik Bandhopadhyay, wrote the classic Bengali novel, Padma Nadir Majhi. In her turn, Banerjee uses erudite arguments, in-depth research and multiple interviews and first-person accounts to highlight why the river’s degradation must be urgently tackled. She juxtaposes the valiant efforts of individuals and groups that continually try to mobilize legal and popular opinion on the Ganga’s behalf with the general disconnect that has led to scale models of the river for simulating tests lying unused, mooted sewage management interventions remaining untested and the local knowledge of those living by the Ganga often going unheard. The demystified, materialistic and technological view of the river from the British era, seeking to channelize it to meet greedy ends has progressively led to its disregard and fostered socioeconomic disparity. She repeatedly warns of the mistakes committed by overexploiting the river’s flow, leaving little discharge to sustain the natural aquatic environment, and of the ravenous extraction of the groundwater beneath its floodplains to meet the requirements of the Green Revolution leading to large-scale agrarian changes. Such alterations have induced arsenic contamination in both India and Bangladesh and resulted in the largest case of mass poisoning in history.

A re-enchantment with the Ganga is thus required — so that the reverence with which it is held translates into impactful endeavours to sustain it by providing the desirable e-flow to preserve this lotic realm, recognize its interconnectedness and re-accord its human rights status. Cleaning the Ganga, Banerjee stresses, is not just a technological challenge but requires greater adaptive steps and mindset changes at the community level, with accountability being key. Only then can the Ganga truly flow in a nirmal (pure) and aviral (unhindered) form — an avowed aim of the present prime minister, which remains far from being achieved.