Book: Silverview

Author: John le Carré

Publisher: Viking

Price: Rs 699

While reviewing a posthumous novel by one of the great Europeanists of our times, it is difficult not to think of another cosmopolitan thinker who has left us betimes, much like, in his own words, “the escape artist, who looks down from a higher point in space at his own absence in time.” This review is dedicated to Aveek Sen, editor, critic, reviewer, essayist, who wrote that sentence in an email to me as we debated the possibility of arbitrating a conflict in which one is trapped in real life: the role that literature or art, I had suggested, plays in the world. In John le Carré’s fictional universe, that rôle is not infrequently given to the elderly, superannuated spy, dragged out of retirement to investigate long-past betrayals and deceits, as if the interval of past time allows for perspectival judgment on his part, when in reality he is as deeply implicated as those he is called upon to question.

Le Carré’s admirers will have picked up Silverview in trepidation, hoping to hear the master’s voice in a book with an unlikely title (supposedly named after Nietzsche’s villa in Weimar, Silberblick, but in English, more apt for something in the thriller category), yet dreading they might find a pale shadow, perhaps a pastiche of the author himself. So the most immediate response of a legion of devoted readers to this novel will be relief: unmistakably, what we have here is le Carré’s voice and accent in a book that summons up the familiar ghosts of Cold War spycraft, fast-forwarded to the bloody ethnic and religious conflicts of 1990s Bosnia, and conjured up in twenty-first century London and the English countryside. In a wind-swept seaside town in coastal East Anglia, a young former-banker-turned-bookseller, Julian Lawndsley, is rather egregiously befriended by a typical specimen of yesterday’s spy (a breed well-represented in the novels of le Carré’s late period) who claims to have been at school with his father. This figure, a multi-lingual East European who now goes by the name of Edward Avon, lives with his dying wife, daughter and grandchild in the local manor house that he has renamed Silverview. It is no surprise to be told (no spoilers here) that the careers of both husband and wife have been passed in the service of MI6, though Edward, recruited in the last decade of the Cold War to be posted in Warsaw, and re-inducted to run British intelligence operations in Zagreb during the Bosnian war, now constitutes a threat needing to be investigated. Enter (though, in fact, he enters in the very first chapter, so is actually first on the fictional scene) a present-day Secret Service agent named Stewart Proctor, who tracks Edward’s and his wife Deborah’s clandestine footprints backwards through a history of affiliation, surveillance and betrayal — in love and marriage, as well as in politics.

As Proctor progresses through the stages of his investigation, there are brilliant reminders of le Carré’s genius: the interview with Edward Avon’s former handlers, former Service top dogs now retired to a ghastly villa in Somerset, and the visit to a Cold War-era US-UK nuclear facility (for storing, delivering and taking hits from devices) located 300 feet under the ground at some unnamed airstrip, whose chain of classified information had ended with Deborah Avon. Equally memorable are an excruciating family dinner at Silverview attended by Julian, and the marvellous, richly detailed comedy of a Service funeral, from which he is abducted to be interrogated. There are typical character vignettes populating the novel’s hinterland — renegade fathers, close but slightly off-kilter marriages, Julian’s fellow-shopkeeper, Celia Merridew of Celia’s Bygones, the Avons’ daughter, Lily, a reluctant go-between in the deteriorating relationship of her parents and the Service. Yet despite all this, the novel remains curiously bare and undocumented, as though it is the groundplan for something that would have been far more layered and intricate when finished.

Early in the novel, Edward Avon introduces Julian to the work of W.G. Sebald, “formerly professor of European literature at the University of East Anglia and now, alas, dead.” Sebald’s Rings of Saturn, a narrative meditation on time, memory and identity that commences in the marches of East Anglia and goes on to embrace “the entire cultural heritage of Europe, even unto death”, is clearly a book that shadows le Carré’s plan for Silverview. Yet this plan remains unrealized, just as lesser questions, too, remain unanswered. Why has Julian given up his high-flying career in the City to reinvent himself as a provincial bookseller, given that he sadly lacks “a basic literary education” and struggles to read Sebald? What makes him yield so readily to Edward Avon’s proposal of setting up a secondhand book club, a “Republic of Literature” (clearly a cover for clandestine activities) in his basement? As so often in late le Carré, our curiosity is less focused on the details of Edward Avon’s treasonable activities as on the secrets of dysfunctional marriages, the clash of principles and loyalties, the progressive futility of Proctor’s quest.

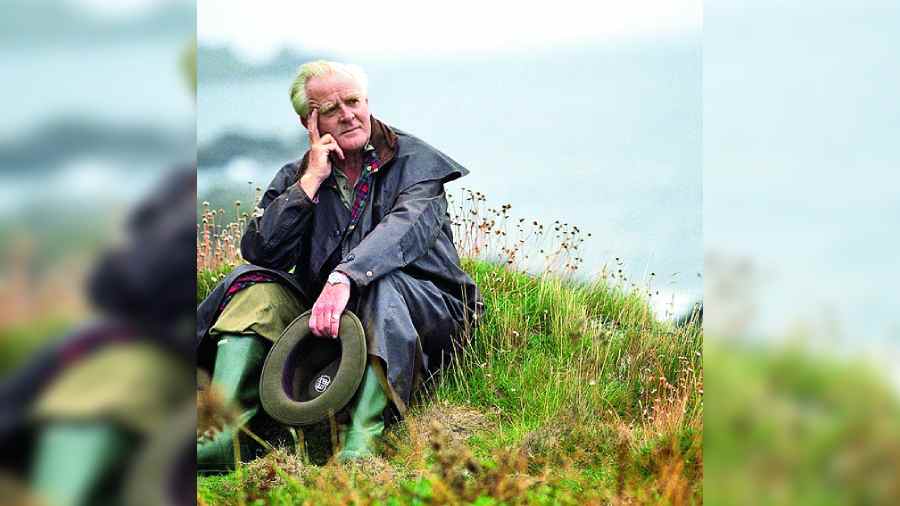

David Cornwell, who wrote under the name John le Carré, died a little over a year ago, on December 12, 2020. His wife, Jane, ill with terminal cancer (like Deborah Avon in this novel), passed away three months later, on February 27 last year. Throughout their working lives, they had collaborated in the writing process, Jane acting as the first reader and editor for all David’s work. When he died rather suddenly, Jane was left casting about, as it were, for the missing material that completed her life and his. Perhaps the somewhat sparse, almost unfinished state of this final novel stands witness to an interrupted collaboration, just as Aveek Sen’s departure interrupts, for me, my reading of Sebald, whom we read together.