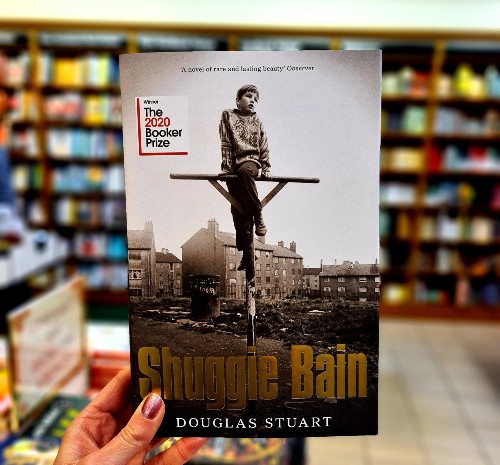

Book: Shuggie Bain

Author: Douglas Stuart

Publisher, Price: Picador, Rs 499

The wonder is not that Shuggie Bain won the Booker Prize this year, but that no less than thirty firms turned it down before Douglas Stuart’s debut novel was picked up by publishers in the United States of America and the United Kingdom. From the opening chapter, set in the south side of Glasgow in 1992, where the fifteen-pretending-to-be-sixteen-year-old Hugh “Shuggie” Bain’s body moves “listlessly through its routine, pale and vacant-eyed under the fluorescent strip lights, as his soul floated above the aisles and thought only of tomorrow” till the final lines which see Shuggie run “a few paces ahead” before “he nodded, all gallus [i.e. stylish, self-confident], and spun, just the once, on his polished heels”, this is a book that grabs the reader by the throat and doesn’t let go until it has wrung out all the wildly oscillating emotions — joy, sorrow, anger, disenchantment, passion, desire, envy, hate, disappointment, and a strange, luminous love — that make up the exhilarating, if sometimes exhausting, experience of reading this dizzying rollercoaster of a novel.

Commentators have made much of the bond that exists between Shuggie, struggling to come to terms with his “unacceptable” sexuality, and his glamorous, broken, violent, tempestuous, alcohol-addicted mother, Agnes, but the novel is much more than a filial love story. Populated with a cast of characters who are as loveable as they are — sometimes — despicable, covering a span of a little over a decade, and set among several generations of the labouring poor of Glasgow, Shuggie Bain casts an unremitting light on those who exist on, or, all too often, under, the fringes of society. Women, men, and children who make the news only when their lives of quiet desperation spill over into something terrible or terrifying — like the 2017 fire that broke out in London’s Grenfell Tower, killing 72 individuals — essentially because of the way in which the poor are “socially murdered” by a largely callous and uncaring government that overwhelmingly privileges the haves over the have-nots.

Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart at Rs 499 Twitter/@Doug_D_Stuart

But to imagine that a novel dealing with lives that are often solitary, inevitably poor, frequently nasty, intermittently brutish, and all-too-often short, is bound to make for grim reading will be to do Shuggie Bain wrong, for one of the wondrous things about Stuart is his ability to show not just the humour that lies beneath the grimness of existence, but also the kindness, empathy, and grace that illumine lives lived on the edge. In large part this has to do with the way in which the city of Glasgow comes alive in Stuart’s supple, sudden, evocative prose, throwing up the contradictions of a city reeling under the onslaught of Margaret Thatcher’s Tory abandonment of the urban underclass (“Thatcher didn’t want honest workers any more; her future was technology and nuclear power and private health.”). As Big Shug Bain, Shuggie’s taxi-driver father, meanders around the city at night, he realizes how “The closer you got to the river, the lowest part of the city, the more the real Glasgow opened up to you. There were hidden nightclubs tucked under shadowy railway arches, and blacked-out windowless pubs where old men and women sat on sunny days in a sweaty, pungent purgatory. It was down near the river that the skinny, nervous-faced women sold themselves to men in polished estate cars, and sometimes it was here that the polis would later find chopped up bits of them in black bin bags. The north bank of the Clyde housed the city mortuary, and it seemed fitting that all the lost souls were floating in that direction, so as to be no trouble when their time blessedly came.”

Yet, there is nothing deterministic about the way in which Stuart goes about framing his tale — people are not doomed only because they have been condemned to poverty by an uncaring government and society, but also because they make choices that are clearly mistaken, un-thought through, and self-destructive — in other words, wholly human and, therefore, wholly believable. It is this that makes his characters come to life: in Shuggie Bain people live, and love, and sometimes die, in ways that — for all their distance and strangeness from us — we can all-too-readily identify with. Who amongst us has not loved a sibling, or a parent, or a spouse, or a friend, even when that love is either clearly misplaced, or unreciprocated, or self-harming, or all of the above? And surely we all know of individuals who have tried to break an addiction and come so close only to slide into failure?

This may be a tale set in a strange city, in times that are receding from memory, but in its humour, its pathos, its depiction of love in all its weird and wonderful avatars and, above all, in its assertion of the essential humanity that resides within every single one of us, no matter how flawed or damaged we may be, Shuggie Bain speaks straight to the heart.