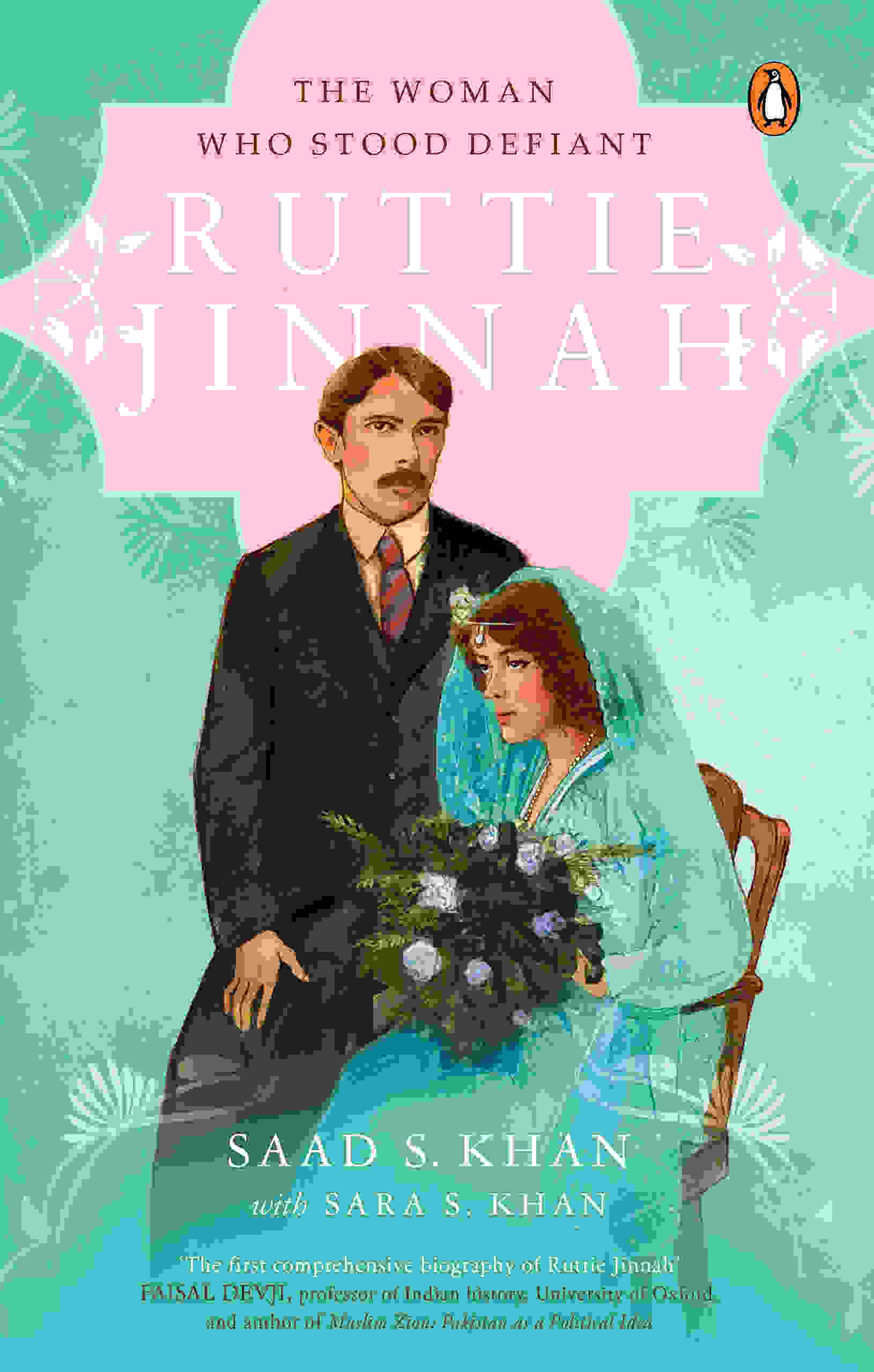

Book: Ruttie Jinnah: The Woman Who Stood Defiant

Authors: Saad S. Khan and Sara S. Khan

Publisher: Ebury

Price: Rs 599

Cocooned from the bustling chaos of the encircling metropolis, in the quiet stillness of the Khoja Ithna Asheri Jamaat cemetery in Mazagaon, Central Mumbai, lies the grave of Rattanbai Maryam Jinnah (1900-1929). Dusty and forsaken, it stands as a silent testament to the neglect and collective historical amnesia that were destined to be her lot after death. For the uninitiated, Rattanbai, or Ruttie as she was also fondly called, was the wife of Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the architect of Pakistan, and her new biography co-authored by Saad S. Khan and Sara S. Khan sets out to unravel the mystery surrounding this enigmatic woman who may have had a significant, although hitherto unacknowledged, role in the shaping of the geopolitical landscape of contemporary South Asia.

The few existing accounts that do mention Ruttie Jinnah (sympathetic or otherwise) are unanimous in their perception of her as a woman of exquisite beauty, charm, and talent, vivacious and impetuous in spirit — traits that earned her the enviable sobriquet, ‘The Flower of Bombay’, from Sarojini Naidu. Her father, Sir Dinshaw Petit II, a rich and influential Parsi business magnate, ensured that his daughter had the privilege of receiving Western education, the luxury of spending summer holidays in England or at the French Riviera or indulging in shopping for expensive clothes, books, and pets. The social eminence of the Petit family among the crème de la crème of Bombay exposed young Ruttie to a liberal and cosmopolitan environment and it also brought her in close contact with Jinnah, nearly 24 years her senior. By this time, Jinnah had established himself as a legal practitioner of repute after his return from England in 1896 and was also a leading member of the Home Rule League that was demanding autonomy for India. If Jinnah’s handsome reticence and political idealism captivated the teenaged Ruttie, her mesmerizing beauty and intelligence caught the former off-guard. Their marriage stunned the nation not least because Ruttie defied both faith and family for her ‘Jay’, but also because Jinnah’s rising political capital as a nationalist leader, especially in the wake of the Lucknow Pact of 1916, guaranteed front-page headlines. They made a striking couple but, unfortunately, the routine practicalities of everyday life soon wore off the romantic sheen from their relationship, causing them to drift apart. Despite their mutual love and respect, differences and misunderstandings kept straining at the last few years of their marriage until Ruttie passed away prematurely of illness at the age of 29. Never a man to display emotions publicly, Jinnah is said to have cried uncontrollably like a child as her body was lowered into the grave.

Ruttie Jinnah: The Woman Who Stood Defiant by Saad S. Khan and Sara S. Khan, Ebury, Rs 599 Amazon

Women-centric biographies offer an interesting intervention in the gender-skewed realm of popular history that still remains a fundamentally male preserve, both in terms of authorship and subject matter. The accommodation of women into a cultural form that documents public lives and reputations is not always a happy one since the need to explore personal and emotional conflicts in a woman’s life has to be entrenched within a larger social network. The present work is no exception, for the historical curiosity surrounding Ruttie and her relevance as a biographical subject are made contingent upon revealing how her forceful and fiery personality influenced Jinnah’s career and political beliefs, especially his commitment to the two-nation policy. The authors cite instances of Ruttie’s anti-colonial demonstrations, displayed in her efforts to stop a memorial to Lord Willingdon, the governor of the Bombay Presidency, or her protest against the deportation of Benjamin Horniman, the editor of The Bombay Chronicle, for the conjecture on her probable role in determining her husband’s subsequent turn into agitational politics. Yet to place the posthumous burden of the Partition on Ruttie’s young shoulders would be to contradict the dense turn of events that transpired after Jinnah returned from his voluntary political hiatus in England in 1934 and assumed nominal leadership of the Muslim community. Moreover, despite its impressive start, the work soon strays into being an oblique account of Jinnah’s political trajectory and the possible private motivations behind his later secessionist sympathies. In hindsight, this is not an entirely unexpected approach to take given the traditional invisibility of women in biographies but, thankfully, the work’s attempt to grant contemporary relevance to Ruttie within the larger socio-political imaginary never comes at the expense of erasing the painful loneliness and frustration of her personal life.

To meticulously piece together and recreate the narrative of a life that has been lost in time is a commendable task in itself, its difficulty underlined by the fact that the book took 12 years to be completed. Whatever shortcomings it may suffer from ultimately are those of history and not of authorship.