Book: On Citizenship

Authors: Romila Thapar, N. Ram, Gautam Bhatia and Gautam Patel

Publisher: Aleph

Price: Rs 499

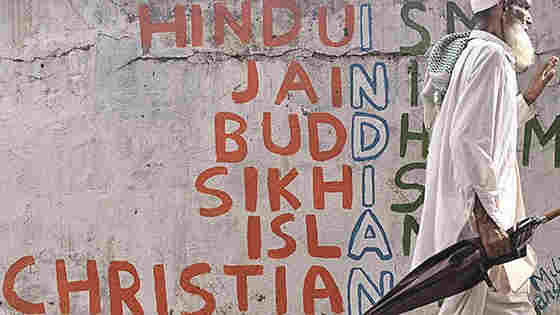

What does it mean to be a citizen of India today? What rights and privileges adhere to the notion of citizenship, and what duties and responsibilities must a citizen discharge in order to qualify as a responsible member of the family of Indians? These questions, which seldom cross the horizon of our consciousness, have taken on renewed importance in the wake of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, especially when considered together with the proposed National Population Register and the National Register of Citizens.

In the opening essay of On Citizenship, “Citizenship: The Right to be a Citizen”, Romila Thapar gives a quick overview of the development of the concept of citizenship in both West and East (including its complicated relationship with race and ethnicity), before going on to assert how, in an independent, democratic country like India, “The state is no longer the patron since the citizen is the one who has established the state.” Relating the idea of citizenship to that of being civilized, Thapar ends her essay with the reminder that “Being civilized also means having institutions that protect each one of us and allow us to both live and die with dignity.”

The next chapter, N. Ram’s “The Evolving Politics of Citizenship in Republican India”, narrows down Thapar’s broad focus to look at citizenship in the context of India, drawing upon the Constituent Assembly debates, the specific and peculiar case of Assam, the controversies engendered by CAA-NPR-NRC and other social and political landmarks to examine how the notion of an inclusive citizenship that gives every adult citizen of the country voting rights — something that is taken for granted by most of us — is both

contingent and presently under threat. He reminds us that the Constituent Assembly debates “make it clear that provision for citizenship [was made] in the specific context of Partition and the coming into being of the Indian nation state with newly drawn boundaries”; something that needs to be taken into account when we seek to better understand the “huge democratic and governance deficits in handling citizenship aspirations and dreams that have been articulated, and contentious issues over the right to citizenship that have cropped up, across a vast and diverse land.”

On Citizenship by Romila Thapar, N. Ram, Gautam Bhatia and Gautam Patel, Aleph, Rs 499 Amazon

Gautam Bhatia examines “Citizenship and the Constitution” in the following chapter, closely analysing the “extraordinary circumstances” in which the Constitution of independent India was framed, and how, despite Partition and the call for a religious basis for Indian citizenship, the framers of the Constitution established a “clear and unambiguous link between the secular character of the Indian polity, and the rejection of racial or religious criteria as grounds for citizenship.” This is the reason why, for example, Part II of the Constitution (“Citizenship”) or, indeed, the provisions of the first Citizenship Act of 1955 cannot be read in isolation but need to be seen as forming “one strand in a web of harmonious and mutually reinforcing principles, which woven together, [make] up the Constitution.” As Bhatia puts it, the framers of the Constitution were “faced with a stark choice: an inclusive and universal vision of Indian citizenship, or a narrow vision that privileged ascriptive identities in prioritizing claims to Indianness. Even before Independence, the Constituent Assembly was clear in its choice: it chose the former.”

In the final chapter, “Past Imperfect, Future Tense”, Gautam Patel brings his considerable legal acumen, many years of experience as lawyer and judge, and an enviable ability to make complex matters of constitutional analysis and legal interpretation accessible to the interested layperson to lay out what he calls the “trifecta” of our Constitution that moves from the general to the specific — “from the Union and its territory in Part I, to citizenship in Part II, fundamental rights in Part III, and so on”, which, he asserts “is not just as it should be, but is the only logically consistent and sure-footed structure”. In keeping with this structure, Patel’s essay moves from an examination of the “relationship or link between citizenship and fundamental rights” to “the attempts in statutes to limit or undermine our basic rights” to “the consequences of very recent political and legislative actions; specifically, some contours of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, or CAA, when set against the Constitution, and issues that have arisen... due to the [ongoing] global COVID-19 pandemic.” By citing landmark cases and judgments from the United States of America, the United Kingdom and India, focussing on those which have subsequently been “consigned to judicial oblivion” due to their wrong-headedness, but where there were dissenting opinions (which have since been recognized for their courage in championing the rights of the individual in a modern State), Justice Patel alerts us to the fact that both the law and its interpretation are dynamic, evolving processes, subject to human fancies and desires; to the pull of power, and the exigencies of party politics.

This slim volume, with its subtly acute analyses of the notion and the operation of the idea of citizenship in the Indian context, is a superb introduction to this fundamental, yet often misunderstood, concept; one that has taken on a renewed, perhaps even desperate, urgency in recent years. It should be essential reading for every concerned Indian, for, in Gautam Patel’s words, “We look back in anger. We look forward in trepidation. For we have faltered before. We cannot afford another misstep.”