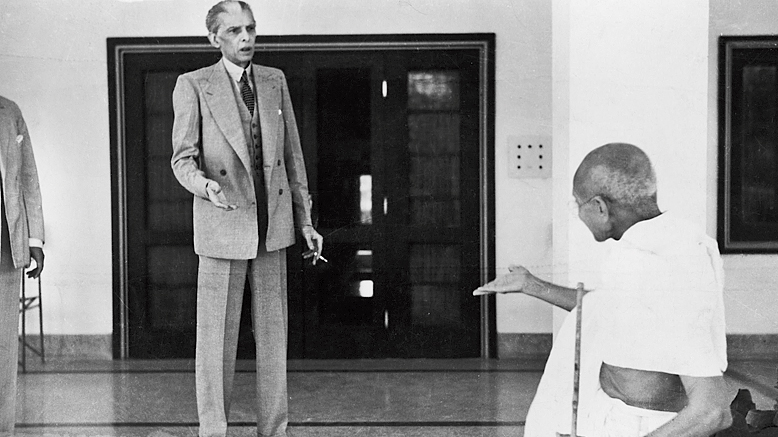

What happened when an unstoppable force met with an immovable object? Gandhi’s epic, but ultimately futile, confrontation with Jinnah — the subject matter of M.J. Akbar’s unexceptional enquiry — is perhaps best expressed in such metaphorical terms. The outcome, unfortunately, was the sundering of the subcontinent into two distinct political entities.

Akbar chooses to explore the dynamics of the Gandhi-Jinnah relationship through the ebb and flow of a choppy political tide. To be fair to the author, a holistic assessment of their engagement is impossible without locating it in its context. But Akbar’s problem is one of control — the lack of it rather — over scale. The attention on the rivalry between the principal protagonists is inevitably diluted as the narrative begins to accommodate other players in the saga. This is not to suggest that Akbar’s broader analysis lacks depth. The differences between Viceroy Wavell and Premier Churchill on the Bengal famine or, later, the barely-concealed antagonism between Mountbatten and Cripps are engrossing. But Gandhi and Jinnah get lost in the crowd on such and other occasions.

Gandhi’s Hinduism, The Struggle Against Jinnah’s Islam by M.J. Akbar, Bloomsbury, Rs 699 Amazon

The fleshing out of the two adversaries is uneven too. Gandhi, understandably, dominates, with Akbar tracing his political journey ably, even though the trajectory of this journey would be familiar to the serious scholar. One inference about the Mahatma, however, does strike a chord. Could the horror of Partition have been avoided had Gandhi, as Akbar suggests pointedly, not “sought to reach Indian Muslims through Jinnah...?” The Jinnah that Akbar portrays is consistent with the prevailing stereotype: ambitious, unbending, tactical and myopic. But what is expected from such an analysis are answers to enduring riddles. Could egotism alone explain the shocking transformation of Jinnah the Constitutionalist? Akbar ticks off Jinnah’s singular speech in the Pakistan Constituent Assembly, calling to bury division among communities, as a subversion of his earlier inflammatory prejudice. Could it be that Jinnah’s obduracy was as much the result of his political aspirations, imperial chicanery as the Congress’s — Gandhi’s? — failure to take advantage of his limitations? Punjab’s Unionist Party, a coalition of Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs, provided the Congress with a formidable alternative to Jinnah’s sectarian model. Yet, Punjab — and Bengal — were bled dry by Partition.

Jawaharlal Nehru — in a sign of the times — comes out as poorly as Jinnah in this interpretation of the tumultuous events with Akbar blaming Nehru for lighting the fire that singed the Cabinet Mission Plan. The shadow of the present on the past seems to be lengthening.