Book name: Fragments Against My Ruin: a life

Author: Farrukh Dhondy

Publisher: Context

Price: Rs 699

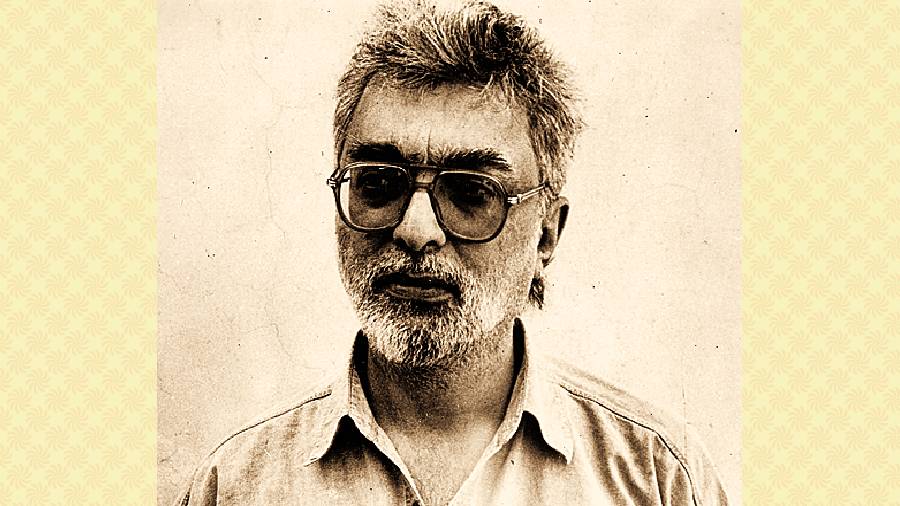

Fragments Against My Ruin shores itself against time, with a historical sense of belonging that a young Farrukh Dhondy hoped one day he would be remembered for: an expat Indian student in London who once turned radical, rebelling against what C.L.R. James identified in history as the “cruelties of property and privilege”. The cover photograph shows a youthful Farrukh sometime in March 1972, then a Cambridge dropout and a part-time school teacher, also a member of the British Black Panther Movement. Farrukh had escaped a racist firebomb attack on a BPM building. The look on his face is defiant. He holds a newspaper like a political placard. The headline reads, “Fire Bomb Attack on Black People.”

Within the span of a few brief chapters, a maturer Dhondy offers his version of the history of BPM. Operating under a broad leftist, albeit diffused, understanding of the term, ‘black’, the BPM fought to unite all black immigrants and non-white working-class people against a racist State. The British Black Panther found greater recognition in 1972 when the art critic and novelist, John Berger, donated to their cause half of his Booker Prize money — it bought them a house prior to the firebomb attack. Dhondy quit soon after.

Black leaders of the BPM like Altheia Jones-LeCointe and Darcus Howe make brief appearances in this telling. They disappear under the rubric of Dhondy’s greater understanding of politics (which remains unstated). However, when the political gets uncomfortably close and personal — as in the case of Mala Sen, the idealistic girl who ran away with Farrukh to England and emerged as one of the prominent leaders of the Indian Workers’ Association and the BPM — Dhondy decides on telling why he mattered. Sen broke up with Dhondy a little before the firebomb attack and went on to become a radical feminist, environmentalist, and anti-rape crusader in India: she was the person who brought to light Phoolan Devi’s ordeals before they were scripted. Here, Sen appears as a nondescript sidekick to Dhondy, the ideologue. At times, Dhondy appears almost paternalistic, insisting that he had been doing good, without exactly spelling out what he was doing or why. And that's all that is told of his political activism.

Following a grand old tradition of autobiographical tub-thumping by leftist intellectuals — Dhondy prefers the term, ‘leftish’ — there is necessary self-aggrandizement and persistent scorn for others who won’t share his vision of the world. From the 1980s, he is quids in with British television though, an opportunity that benefits him creatively, as he remodels his future through Tandoori Nights. But the battle continues on the ideological terrain. Dhondy continues to scoff at people he identifies as “champagne socialists” (who, through implication or conceit, are identifiable as Anand Patwardhan, Arundhati Roy and some unnamed Indian friends of Tariq Ali). Understandably, in the course of the book’s twenty-seven chapters, Margaret Thatcher gets mentioned only once.

The greater part of the book details the actions of an older (which is the polite way of saying grumpier) Farrukh Dhondy: one of the longest-serving commissioning editors in the history of State-funded British television; Charles Sobhraj’s confidante and author of Bikini Murders; the asli scriptwriter of Bandit Queen and Jinnah; a true-blue friend to V.S. Naipaul and defender of his ahistorical rants about Indian Muslims on television. As they say it in Britain, everything appears tickety-boo after this.

Another of his friends, the Trinidadian historian and philosopher, C.L.R. James, plays a cameo in Dhondy’s reminiscences. Here Dhondy approaches James to seek advice about his new television job. (This seeking of advice seems pointless for Dhondy had decided on it already — he couldn’t resist chronicling the ‘equal opportunity’ shortlisting process, the process of pulling strings at various levels, and an on-the-spot manipulation of one of his interviewers.) James, reportedly, was reading Thackeray’s Vanity Fair. He pointed one finger at the book he was reading, “shook his finger from side to side to indicate some form of negativity”, and then pointed at the television set that kept playing on in silence in the background. For Dhondy, it was a moment of epiphany: he thought that James was “indicating that it was the future”. This incident sits big on the book’s dust-jacket.