Book: Caste: The lies that divide us

Author: Isabel Wilkerson,

Publisher: Allen Lane

Price: Rs 999

One of the many prerequisites of efforts to create a casteless society is one’s perceptual clarity about how lies divide peoples in a way which, among other immoral consequences, dehumanize the subject castes and the dominant caste. Many cultural devices collaborate among themselves to induce and institutionalize misrecognition of deception that secures morally impermissible inequities. Rarefied philosophies, mystifying religions, engaging myths and local tales of spoilt identity work together in the construction and the persistent circulation of a sense of normality to social differentiation, leading to discrimination in the distribution of socially-valued resources like money or its analogues, power and esteem. The founding lie — with its derivatives — is obviously the one on natural hierarchy in every society. However, from time to time, the undying “human pathogens of hatred and tribalism” break out of the “permafrost”, as is the case in contemporary United States of America and India, and the lies lose their wrap. The lies cannot prevent the backlash or the emergent, awakening human goodness forever. Like a “house inspector” looking at “the misshapen ceiling... [with] infrared camera”, Isabel Wilkerson had to write Caste in such a moment: she had to understand caste in the US and beyond and envisage the conditions under which it can be challenged comprehensively.

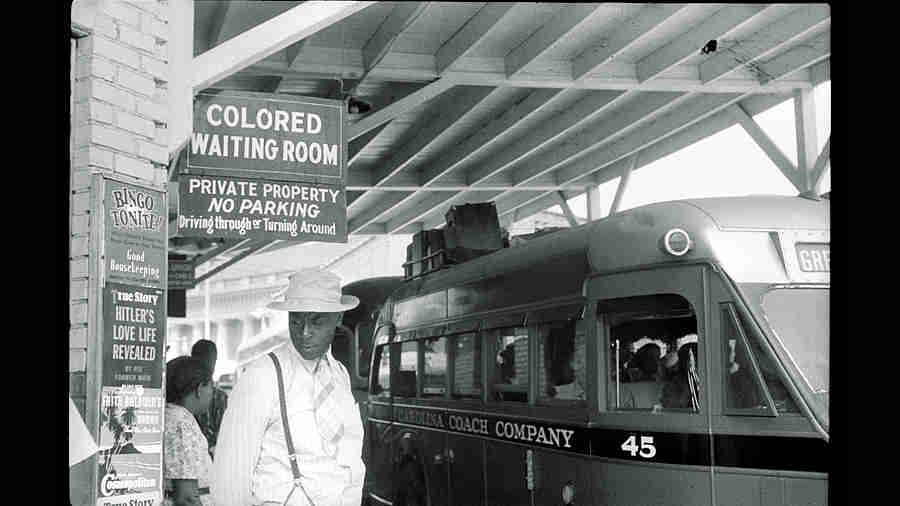

True, her point of departure is race in America, particularly its southern part. But she prefers caste, which directs her analysis of morally impermissible social divisions to their elaborate institutional foundation, to race — “the visible agent of the unseen force of caste”. She takes over from B.R. Ambedkar the conception of caste as a notion; a state of the mind. On it, she rests her thesis that the moral transformation of the individual in both the dominant and the subjectified caste is vital for making caste redundant. Although she is inquisitive about “the shape-shifting, unspoken, race-based caste pyramid” in the US, for a deeper understanding of the American caste inequity, she compares it with the “lingering millennia-long caste system of India” and with the “tragically accelerated, chilling and officially vanquished” Nazi caste. In her comparison with the Hindu caste order, she deploys powerful metaphors to analyse caste’s stranglehold over the two stratified societies — India and the US — such as the architectural metaphor of pillars, a set of untested and unverifiable assumptions about people, both the superiors and the outcasts; or the zoological metaphor of tentacles to explain how the hierarchy is protected in the face of inner anxieties; or the biological metaphor of toxin to bring out its psychopathology like hate and narcissism. The comparison with the Nazis reveals the dark side of the US republic. In the early 1930s, while pondering the way of creating a legal framework for an Aryan nation, the Nazis wanted to know how the white-dominated US “protected racial purity from the taint of the disfavored”. But even the Nazis considered the one-drop rule (of Negro blood) to be too harsh (even) for them. They adopted only the slur word, Untermensch — under-man — from the American eugenicist, Lothrop Stoddard, to dehumanize the Jews. Apparently some German people, not always Nazis, “ingested the lies of an inherent Untermenschen”. How to behave with their Other became a part of muscle memory.

Caste: The lies that divide us by Isabel Wilkerson, Allen Lane, Rs 999 Amazon

Wilkerson’s disturbing micro-narratives of the dominant caste’s arrogant claims of entitlement with disregard for others, its scattered sentinels in anxious surveillance of the slightest sign of difference and transgression from below, ‘Stockholm Syndrome’ of people bonding with their abusers, and rewards for snitches and sellouts among the lowest caste are more or less true about all closed, stratificatory societies that deny legitimate opportunities for upward mobility to the repressed castes.

For Wilkerson, the key agent of transformation in any society divided on ascriptive identity must be radicalized individuals courageous enough to cope with the costs of engaging with the people in the dominant caste and their cultural and political apparatus; like August Landmesser, a shipyard worker, who refused to salute the Führer in 1936. He knew that the Nazis were administering intravenous drips of lies about the Jews. However, the number of such persons with radical empathy and personal experience of dehumanization must be very large so that “the flap of a butterfly wing” can build “a hurricane across an ocean”. Wilkerson is obviously interested in the end of caste in the US but she is wise enough to acknowledge the imperative of simultaneous global transformation. Even though the author perceives caste hierarchy in terms of power-holding rather than of feelings or morality, she writes with a moral commitment to the vision of a “world without caste [that] would set everyone free”. What we have to do is to exercise our choice: “We can be born to the dominant caste but choose not to dominate. We can be born to a subordinated caste but resist the box others force upon us.” The lies must be unmasked.