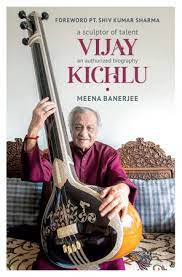

Book: A Sculptor of Talent: Vijay Kichlu — An Authorized Biography

Author: Meena Banerjee,

Publisher: Roli

Price: Rs 595

A Sculptor of Talent: Vijay Kichlu is an authorized biography of Vijay Kichlu, doyen of Hindustani classical music and executive director of the well-known ITC SRA or Sangeet Research Academy.

As expected, the author dedicates a large part of the text to the founding and the earlier years of the SRA. However, the text pays equal attention to Kichlu’s projects and commitments throughout his life, namely, being the founder-director of SRA, the organization of numerous concerts, the 52-episode project of DD Bharati on appreciation of Indian classical music, the founding of Sangeet Ashram and so on. The text does focus more on Kichlu the business head, the organizer, the passionate musician; it paints Kichlu as a man with a mission, eager to guide and mentor. But the text also does not shy away from the image of Kichlu as the dutiful son, the perfect sibling, the loving husband, the doting father, and the ideal friend. It attempts to provide as complete a character sketch as possible of the multifaceted and multitalented personality.

Founding the SRA laid much emphasis on the traditional guru-shishya parampara, so revered in Hindustani classical music as the most effective, supremely spiritual and, often, the only way to get trained in music. Kichlu’s novel venture in 2002 came in the shape of the Sangeet Ashram, where he took up the unique responsibility of generating interest in a lay audience — an audience that was uninitiated in Hindustani classical music. In a way, this was more significant than producing competent performers because a knowledgeable and appreciative audience is hard to come by in any genre of performance arts. More than the making of the listener, or the producing of the performer, Kichlu was clearly bent on creating the figure of a true teacher of music, or a guru. As he himself said in an interview, “[M]ost of the institutions have done nothing to create able gurus but it is they who keep the flame burning. Unfortunately not even SRA-products, who are technically extremely proficient, can claim to be great gurus.” Overall, the emphasis has always been on authenticity and purity, as Kichlu himself has declared on occasions. The book does not dare to deviate from this self-proclaimed vision, staying true to its claim of being an authorized biography.

A Sculptor of Talent: Vijay Kichlu — An Authorized Biography by Meena Banerjee, Roli , Rs 595 Amazon

The most interesting part of the biography is the episode about the founding of ITC SRA — the way A.N. Haksar, the first Indian chairman of the Imperial Tobacco Company, later renamed as the Indian Tobacco Company or simply ITC, has an inspired business idea that also created a credible image of social responsibility and how his proposal wins Kichlu over. The narrative is also strewn with interesting anecdotes from the world of Hindustani classical music. The anecdotes recount events taking place over a long period of time, thereby illuminating the changing structures and conditions of the classical music scenario, both gharana-based and individualistic.

The sudden homily in the middle of the book on the definition, history and evolution of Hindustani classical music, although couched in the guise of the curiosity of Kichlu’s wife, Kunti, feels like a harangue right in the middle of the smooth telling, as does the sudden inclusion of what reads like the shortened version of an SRA report. These interrupt the otherwise even flow of the biography.

While receiving the prestigious Sangeet Natak Akademi Fellowship in 2014, Kichlu’s first reaction was to declare the news as “a great surprise”, an honour which made him feel elated yet weighed down. Kichlu further said, “I consider that the SRA-products, which I gifted to the music world, are my best awards and I wish I could produce some more worthy musicians.” Yet, elsewhere, Kichlu says, “Our classical music is one subject which cannot be taught in a group; which cannot produce top performers en masse.” Together, the statements appear to display a covert duality of attitude where, on one hand, there is an urge to not let the various gharanas of Hindustani classical music dwindle and die out and, on the other, a tendency to manufacture performers out of a production line. The biography does not try to synthesize the perceptibly dissimilar points of view, but leaves it open-ended for the reader to figure out.