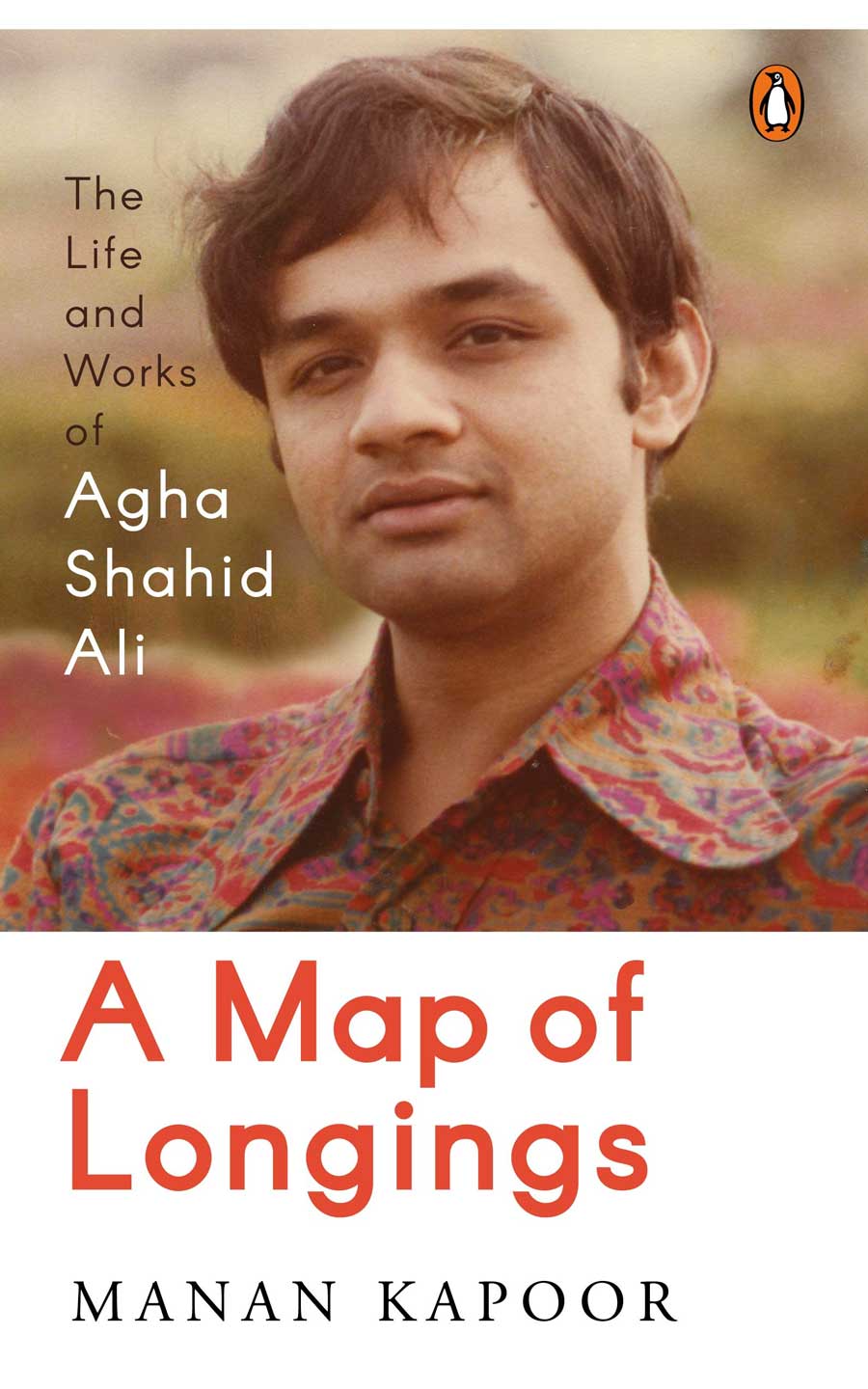

Book: A Map of Longings: Life and Works of Agha Shahid Ali

Author: Manan Kapoor

Publisher: Viking

Price: Rs 499

Agha Shahid Ali created “another country/ where the sea is the most expansive blue,” and gave us the exquisite The Half-Inch Himalayas, intricate paisleys and Dacca gauzes in his resplendent and resonant body of poetry on Kashmir, America, love, loss, nostalgia, (in)justice, and more. Manan Kapoor has swum in the seas of Shahid’s creations, climbed their summits, and traversed their recesses. If you are interested in South Asian English poetry (or even South Asia), you must read Agha Shahid Ali. If you are interested in Shahid, you shouldn’t miss Manan Kapoor’s A Map of Longings, a lush new biography of the poet.

Kapoor has built on the growing biographical and critical literature on Shahid’s life and writing that has mushroomed in the two decades since his demise in 2001. He has conducted extensive interviews with the surviving protagonists from Shahid’s life and collected material from anecdotal and published testimonies, interviews, letters, and critical essays to reflect on Shahid’s poetry. The various stages of his poetic life under their different influences are charted for the reader with great élan.

What struck me most strongly about Shahid from the biography was the early access he had to a surfeit of culture from northern South Asia. With an educator father close to Sheikh Abdullah and Zakir Hussain, the young Shahid had the privilege of interacting with the cultured elite of the subcontinent, such as the Indian president and the prime ministers of India and Jammu and Kashmir. The undeclared poet laureate of the north, Faiz Ahmad Faiz, was a visitor to the Agha household as was, later, the queen of ghazal, Begum Akhtar. Shahid would, of course, write about Begum Akhtar and her loss in his poetry, just as he would translate Faiz’s poems and go on to write masterful ghazals in English, righting the English ghazal tradition.

A Map of Longings: Life and Works of Agha Shahid Ali by Manan Kapoor, Viking, Rs 499 Amazon

Shahid wrote his PhD dissertation on T.S. Eliot, and Kapoor traces his strong influence on the former. Eliot’s work allowed Shahid to remove himself from his personal experience to write from that emotion. This also explains his motivation to not write of his homosexuality as the centre of his writing. Love, longing, and loss were important, but not necessarily their manifestation. Shahid’s exposure to London, Delhi, Kashmir and America, particularly the role of their landscapes as influence on Shahid’s poetry, is also well mapped out. The poet, James Merrill, is identified as another major influence for Shahid’s turn to formalism, which led to his prolonged and career-defining engagement with the ghazal and forms such as the ‘villanelle’. Kapoor makes other astute observations on Shahid, such as his verse always having the sense of being in translation, like Paul Celan’s. He also brings alive Shahid’s personal wit and charm.

Kapoor is evidently a fan, and admits as much in the Introduction. I too am a fan of Shahid and wrote much of my first collection of poems, Ghazalnama, under the influence of his verse. Still, I remain alert to his errors and foibles, such as his calling the continuous ghazal or ghazal-e-musalsal a qata, or four-line verse, comprising two shers in his Introduction to Ravishing DisUnities, to name but one. Kapoor has dived deep into Shahid’s “most expansive blue” sea of poetry, and his biography rekindled my interest in Shahid, leading me to write poetry, once again, under his influence after a long hiatus. For this, I thank Kapoor. Still, I must point out that he runs the risk of drowning in Shahid’s own self-fashioning when commenting from the inside. While reading a poet on his or her terms is desirable to an extent, as biographer and critic, one should not lose one’s own criticality and become a cheerleader. If Shahid admits to learning from Eliot the critical emotional distance from the autobiographic in his verse, the influence of similar non-autobiographic, yet emotional, affectations of Urdu poetry on Shahid should have also been evident to the biographer. If Shahid, with a lack of criticality, claims to be the product of the imprecise and unequal “Hindu, Muslim, and Western” cultures, Kapoor could have exercised more caution while using the quotation just as Daniel Hall did in his introduction to Shahid’s The Veiled Suite. There are conceptual imprecisions, such as calling Shahid “completely South Asian and completely cosmopolitan”, as if these

are mutually exclusive categories despite the multilingual, multireligious, multi-ethnic nature of South Asia. There also lie other errors, such as India’s “300 years of colonial rule”.

Nonetheless, these minor failings arise from the same love, if not obsession, that has brought to us this richest of witnessings of the beloved Agha Shahid Ali in his full poetic glory. Shahid had asked: “... how could someone like you not live forever?” Kapoor has shown that Shahid lives on robustly.