According to James T. Kirk, space is the final frontier. Tim Marshall seems to agree with Kirk and argues in this book that space is rapidly being invaded by everyone who wants a stake: rich nation-states and private companies with deep pockets, along with poor nation-states aided by rich private firms. From difficult discussions about the privatisation of space — Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin spacecraft which carried William Shatner, the man who played Kirk, past the Kármán line certainly falls within this territory — to an analysis of the 21st-century space race, The Future of Geography has it all.

The book starts off by recounting the short history of astronomical study since ancient times. Once this foundation has been laid, the various categories into which humankind has divided outer space are explained. For example, low earth orbit is where satellite imaging takes place, while the geosynchronous sphere is the domain of telecommunications satellites. As the biggest piece of prime real estate in outer space at the moment, the moon is placed at the centre of a new space race — which nation will develop technologies capable of “setting up shop” on the moon first? Which company will be able to mine an asteroid for rare metals? Your mind jumped to Elon Musk’s SpaceX on that last question, I know.

Marshall uses global political relations on terra firma as a springboard to dive into the world of “astropolitics”. And as below; so above: the astropolitical landscape is dominated by the three big powers: Russia, China and the United States of America.

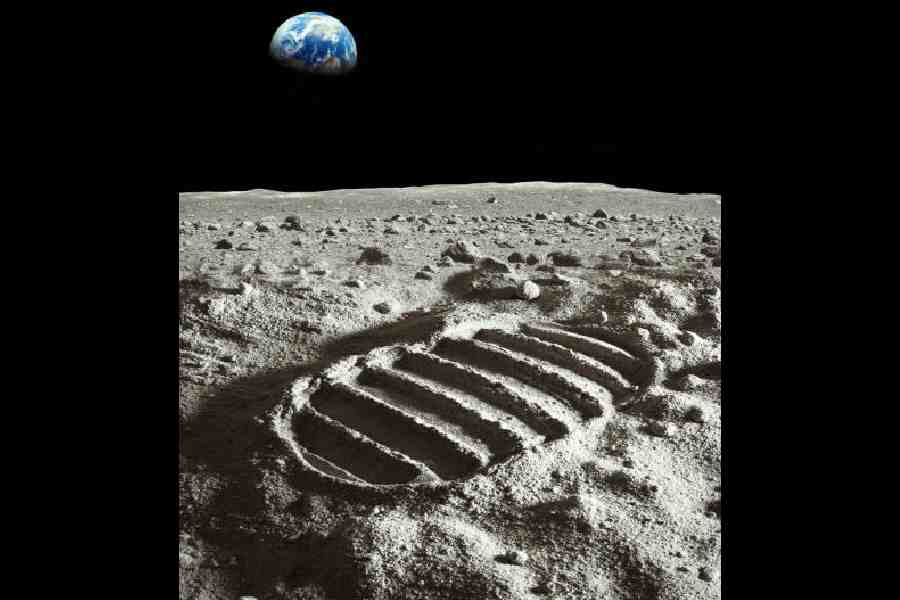

Marshall does not tell us anything new about the history of space exploration; we are already aware that Russia had been at the vanguard, but the US got to the moon first with ‘one giant leap’. It is in its scrutiny of the growing divide between civilian and military expansion in space that the book shines. Washington is as heavily invested in its Tracking Layer, a group of satellites meant to act as a defensive shield, as it is in the Artemis programme. Russia is arguably more concerned about Kalina, a defensive laser technology, than it is about its cosmonauts. In the civilian sector, China’s recent advancements have been stupendous; it became the second country to land a rover on Mars and the first to land an unmanned spacecraft on the far side of the moon. India, of course, has not been left behind; Chandrayaan-1 found evidence of water on the moon and in 2019, we tested an anti-satellite weapon under Mission Shakti.

The book ends with ominous warnings about how human beings are taking their predilection for war into space — the newly formed Space Force in the US armed forces' arsenal is an example. Emphasising that the “necessity of cooperation is what kept the airlocks open,” Marshall advocates the use of space’s resources in order to build a more equitable future.