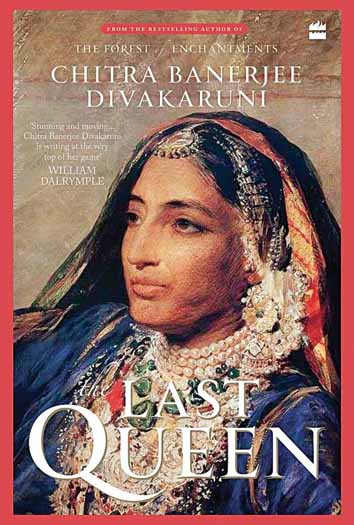

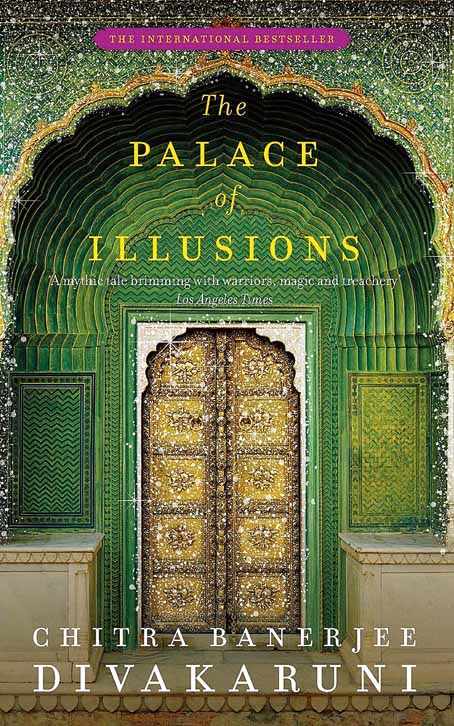

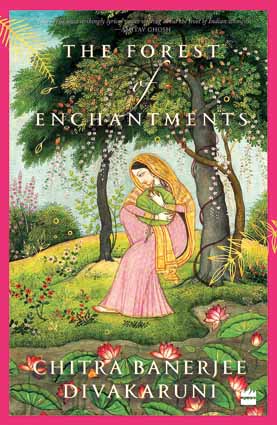

There is laughter in her voice when she speaks and that makes one feel like life is to be experienced with unbridled joy, even in the face of extreme pathos. That’s Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni for you, a rush of fresh air on a weary day. She has previously written about Draupadi and Sita in a retelling of the epics that are so unique that they won the hearts of fans worldwide. Her books Palace of Illusions, Mistress of Spices and Forest of Enchantments have legions of women drawing strength from the protagonists. And now that she is ready with her latest book, all set to the release on January 20, The Last Queen (HarperCollins India; Rs 599) is her foray into historical fiction. Writing about an elusive queen of Punjab, Rani Jindan, whom history has often ignored, The Last Queen is a different flavour of the author we have all grown to love, the author who gives agency to women from the greatest of epics.

Speaking to t2oS from Houston, the author’s voice is like a balm of positivity in the face of extreme drudgery. She talks about what drew her to the character of Rani Jindan and how learning to take online classes in her university was a challenge in this lockdown. Excerpts.

How has the lockdown treated you?

Oh my! It’s been quite a year for all of us, hasn’t it? It’s been unlike anything I have experienced in my entire life. Teaching online has been a task and we got crash courses from the university on online teaching. There are so many new software! I am blessed because I teach senior students and they are very motivated. They are all working on books themselves and they want my feedback and find ways to better themselves. They were so enthusiastic and that’s what saved me.

Since you are surrounded by aspiring authors, do you think the lockdown has impacted their want to write?

I think people have really focussed. I saw that for myself too. When the pandemic broke out, we were all so concerned. But once we figured out how to live our daily lives, order groceries and do our jobs, I felt like the pandemic took away a lot of distractions for me as well as my students. All the time they would have spent socialising with people or even getting dressed for a party, was gone. We had the opportunity to focus on our work and our art. I saw this for The Last Queen, where I found myself going to my desk every time I would feel overwhelmed by the happenings of the world. Here in the US, there have been political upheaval aside from the pandemic — things that I would be really concerned about and would want to help with but was unable to. So, I would say that my work really saved me. Of course, we want to be caring and responsible citizens but there are a lot of things that we can’t do anything about. However, what we can do is focus on our art. We all got a lot done and I finished this book in the pandemic.

So why Rani Jindan?

I had been thinking about her ever since I came across a story, interestingly at the Kolkata Literary Meet! William Dalrymple and Anita Anand were doing a presentation on Kohinoor. The Kohinoor and Rani Jindan’s story intersects for a little bit but they talked about it and how it was taken away from her son Maharaja Dalip Singh.

She was in prison and he was exiled in England. She escapes to Nepal and meets her son after he carefully orchestrates a meet. Just her story really touched my heart. As a mother, I could feel her pain. And I felt that what was done to her by the British was so wrong and yet she didn’t lose her spirit and was so courageous.

In the end, when she finally sees how they had colonised her son’s mind and made him into a fake Englishman, where he had lost his sense of religion and who he is, she dedicates the last part of her life in just bringing him back to himself. I was so impressed by that. Not only is this a wonderful and very human woman but nobody has really written her story — not even in non-fiction or history books. I had to do a lot of research to find facts about her.

I was just coming to that — since so little has been documented about her, how did you research her?

I had to go at it sideways. I read up everything I could find on Raja Ranjit Singh and then on Raja Dalip Singh. Of course, lots have been written about them and therein lies the irony — history remembers the men, it chooses to forget the women.

Through books on them, I would find references on her which I would follow to find letters she had written, articles she put out in Punjabi newspapers. She was so loved that she had a whole network of spies who would get her letters of protests which she would get published. There were eyewitness accounts in the Lahore Court; there were accounts by Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s physician for instance, who wrote a lot of things. What was very interesting is that after her son is separated from her, he is given to an English couple, Lord and Lady Login, as guardians and the latter turned out to be a huge diary writer! Her views on Jindan gave a great perspective on how the British thought about her.

When you really start digging, there are lots of mentions of her by the British officials of that time. They created a huge smear campaign against her and it was horrifying. She was so loved that they had to plot ways to denigrate her and make her people feel ashamed of her. They created fake liaisons and affairs in her life and they called her Messalina of Punjab. So sideways, looking at her, I got a sense of her. Lady Logan writes a lot about her after they leave for England because they are convinced that she would negatively influence Dalip Singh who was extremely well-behaved.

You have moved from recreating mythical characters to historical ones. Do you feel there is more poetic license in the former than in the latter?

Yes, there is, although in the Forest of Enchantments and Palace of Illusions, I set some guidelines for myself; very clear boundaries — that I will not stray from the original epic. Valmiki was a very great source for me as was the Bengali Krittibas. If I didn’t find any major difference with the major retellings, I wouldn’t change the main gist of the story.

There, what I wanted to focus on was the character interpretation. Why does Sita or Draupadi do something? Because the texts don’t give us, they just give us the events. I felt that I could really interpret the characters according to my understanding of their true nature and the role they played as well as their worldview.

I was already putting a lot of boundaries on myself and what I was allowed to do. I really wanted everyone to feel that this is not a Sita that Chitra Divakaruni has made, that this is the real Sita who we are supposed to see but who has been buried under patriarchal conventions, in the time between Valmiki and Krittibas and our time.

However, in history, I get more constrained because I couldn’t change any of the main events in Jindan’s life. It would cease to be authentic if I did that. All of the main events are just as I found them, to the best of my knowledge. What I changed are private moments.

All we know is that she comes from a very poor background and her father is the royal kennel keeper for Ranjit Singh and yet he marries her. That is the power of her charisma and beauty. I imagined what would happen when she is in the zenanas and all the other ranis would be jealous of her. There is no information about that, so I felt free to imagine.

So which parts did you love recreating the most?

I loved her childhood and her relationship with her brother Jawahar. That was really important because later she calls Jawahar when she becomes queen. She asks him to come and he gives her a lot of trouble because he is not an easy person and he’s always getting into trouble, doing the things he shouldn’t be doing and yet she loves him so much. So I felt, it was really important to set up this relationship from childhood. Why would she do all that? Why would she have him stay at court even though he was causing problems for her? I really wanted to show that.

The other part which was interesting for me was to show her relationship with the maidservant Mangla. She is a historical character who has been mentioned in historical accounts. Just the kind of loyalty she inspires in Mangla was worth exploring. I enjoyed writing that part.

And I think I really enjoyed writing about the time when after many years, she meets her son again. I enjoyed it but it was very poignant. Tears would come to my eyes as I’d be writing about this mother seeing her son after so many years, and he had changed so much. She was worried about whether they could relate to each other and if they could love each other. As a mother, I really felt that portion.

What is the one lasting emotion that you would want your readers to come out of this book with?

Maybe more than one, I think, which are almost contradictory to each other. I want them to admire her for her courage and intelligence and her determination to not give up even though the British gave her so much grief. Apart from the misery, they took all her money, jewellery, put her from one prison to another. But she never gave up even though her health began to fade.

They kept her in terrible conditions in these fortresses, but she was so indomitable that she never gave up. I want my readers, especially my women readers, to be inspired by that. Here’s a woman living with such difficulty but she believes in herself. She doesn’t give up. She says ‘I will escape from this fortress’ and she does. And she goes all the way to Nepal even though she’s not in good health or has money to take asylum. So I want people to really admire her for her strong will power.

And I want people to love her because she loves the people in her life so much. She loves her husband dearly and is very loyal to him. I want people to see this softer side to her. It is important in our Indian culture because we need to understand that our great mythological heroines, such as Sita and Draupadi, had one side that was loving and giving while the other side was resolute enough to not give up or put up with the nonsense around them. I want people to enjoy both sides of her, to experience how much courage or love it took for her to go and spend her last years when she was not even well, in the land of her enemy. She went just because of the love of her son to whom she wanted to give back his pride in himself and in his culture.

In the current scenario, do you think women are able to claim their agency more? How do you think the reception of it is evolving or is it at all?

This is true for every society, be it the US or India. So much of it depends on where the woman is coming from. Some women are better off in their current situations. They are able to work, be financially independent and these things allow them to have more agency. Sometimes, if they are lucky, they get to be together in a group and the group empowers them. And that’s something I have observed while working for many years in the field of domestic violence with various organisations.

Sometimes, when a woman doesn’t have anything else, she needs an organisation to stand up for her. I think there are more organisations educating women for various situations but there are so many women who are not receiving this education. I think for every woman, no matter what the situation is, if she reaches inside of herself and finds strength, she can improve the situation. She may not be able to solve the problems that she is facing but she can definitely improve the situation and feel better about herself.

Your Mistress of Spices has been made into a film and your other books have been adapted for plays. How do you feel when your book gets adapted to another form of art?

I’m always excited in the early stages when people talk about the ideas and ask me how I visualise the scene and what I want the actress to portray. Early in my life, I came to this conclusion — and even my writer friends told me — that the book is mine but the movie is really someone else’s. It belongs to them — the actors and actresses. I have to loosen my grasp on that. I can’t expect to control it. Once I realised that, I was quite excited to see what happens to Jindan’s character. It would just sparkle on screen. She’s so clever!

Another friend said something similar: If your book is made into a movie, it’s a win-win situation. People might love the film and reach for your book or they might not like the movie as much and then they'll say the book was better!

What would you say is different about this book from all your previous ones?

Let’s just say that I learnt so much while writing it! I had read about the British occupation in so many books but the methodical process of it all baffled me. The insidious way they went about destroying kingdom after kingdom is unfathomable. They had so little respect for India and Indians. I had very little idea of how little respect they had for this wonderful country. And as I read more into it, I grew more determined to write her story where we see the truth of what went on and where people did fight with great courage for their land against the British.

I observed how they failed when they couldn’t come together and I think there is a political lesson there as well. And that lesson says that if we can’t come together, whatever country it is, we are going to destroy ourselves. That’s why the great empire of Ranjit Singh falls, because the moment he passes, people start looking out for themselves. And as a country, I have felt that we can do that — unite ourselves. Everyone in the country needs to find that common vision of something they care for and love about their country. I think that was a great lesson for me, a timeless one at that, very appropriate to our contemporary times.

Is there any book you picked up in the last year that you loved or wished you had written?

When I am deep into a book, I try to not indulge in others because I don’t want to be distracted from my fictional world. But one book that I read and went back to again and again and actually learnt a lot from is Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall. It’s set in King Henry VIII’s time and there are lots of similarities between then and the Punjab I wrote about. I really loved how she portrayed the depth and the complexities of the characters. I thought this is what I want to do! (Laughs)

Have you found inspiration for your next?

I feel like this novel, as I was saying to you, has put me in a historical time frame. So I am thinking of another historical novel and I think that now I am interested in India during Independence. I want to think about the time when India does become independent — what was that like?