Living Without the Dead: Loss and Redemption in a Jungle Cosmos By Piers Vitebsky, HarperCollins, Rs 799

India’s tribal religions are very little understood: personhood and the spirit world are construed in a radically different mode from how a “modern”, “educated” person thinks and, in many ways, the Sora highlands when Vitebsky first lived there in the 1970s were in a time warp, sheltered from “modernity”, which entered alongside Christianity, and which shamans in many ways rejected.

The strength of Dialogues with the Dead was in showing the complexities involved in what we call shamanic possession, reproducing long dialogues, which are “simultaneously religion, psychotherapy and law”, that people hold with dead relatives and neighbours who speak through the shamans’ mouths. Healing and death rituals both deal with spirits known as sonum. They are associated with a particular place and the spirits of ancestors who died through a particular sonum “eating” them. In many ways, shamanic sessions act as a highly evolved kind of community drama therapy that most “modern” people never experience, since shamanism represents an antithesis to modernity, a genre of human expression that was completely suppressed over the centuries on the grounds that it was demonic possession, punishable by death throughout most of the Christian era.

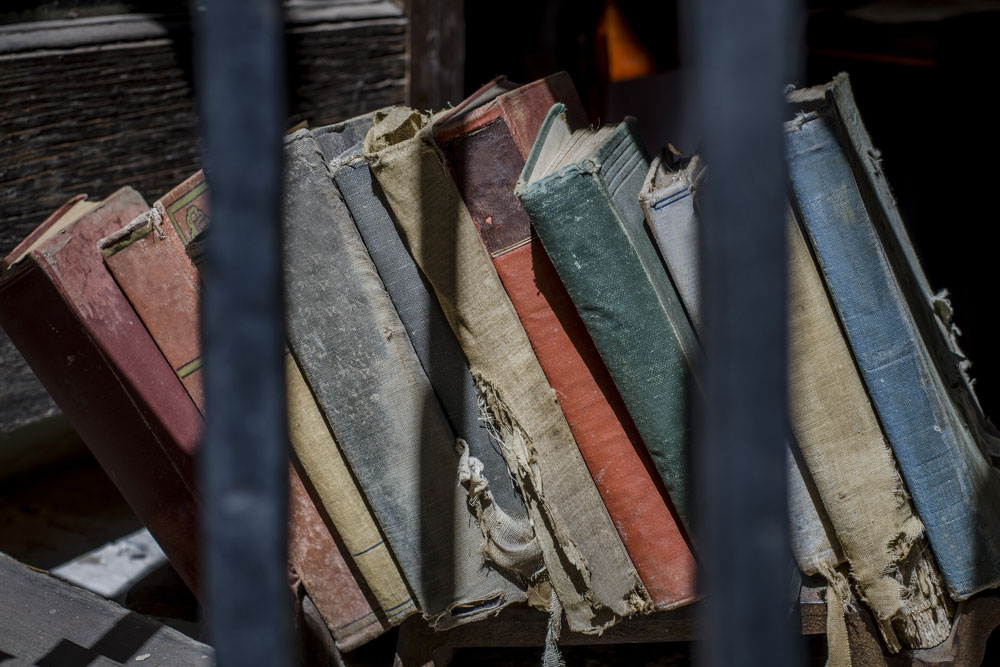

The present volume moves back and forth across the author’s long involvement with the Soras. The rich data emerge out of personal experience along a steep learning curve, with vivid description reinforced by excellent photographs, emphasising the strength of personality and expression associated with shamanic experience. Unlike “conventional” anthropology, the ethnographer here makes no attempt to conceal the relationships through which he learnt — quite the reverse, which makes for great honesty as well as emotional immersion.

The book is deeply tragic, in depicting a dying tradition of immense richness, in myth, music, human expression and imagination. Yet, there is no glossing over the “good old days”. Even before the 1970s there was immense exploitation and consequent indebtedness and deforestation, with Sora headmen sometimes complicit in extreme exploitation of fellow Lanjia ‘slaves’. In fact, the first impact of modernity swept away the archaic feudalism associated with remoteness, and Christianity evidently appeared “liberating” because of this sweeping away. Some shamans also practised sorcery, and sorcery accusations (mainly against men, not women) were (still are?) a blot on social life. Most shamans were women (unlike in some other tribes, such as Gonds), and the turn towards Christianity (as towards orthodox Hinduism) has involved more patriarchy than ever existed before.

As in other shamanic cultures, a shaman’s initiation is extremely demanding and painful. Sora shamans have marriages and children in the underworld as well as above ground, commonly marrying a spirit-child of their main teacher. The spirit-spouses who guide living shamans were conceived as ‘high-caste’ and literate, unlike the shamans themselves. A visit to a section of Soras who practice a Hinduised form of the traditional religion shows shamanism continuing, but in a highly attenuated form, in which spirits speak, but full dialogues between people and their dead relatives are largely missing; and the cult venerates a Sora script, in preference to the spoken language.

Living without the Dead raises many questions about how anthropologists understand social change. Lanjia Sora are one of the communities now categorised as Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups, and it is instructive to compare processes of change among other PVTGs. Among Dongria Konds in Niyamgiri, the modern world has impacted them through activism, media and politics, tourism and CRPF camps hunting Maoists. Among other groups in south Odisha, such as Bonda, Didayi and Gadaba, it has involved even harsher negative stereotyping and demeaning programmes promoting assimilation into the mainstream. Among Paudi Bhuiya in north Odisha and Konda Reddi in Andhra Pradesh, it has involved mindless governmental pressure to “come down from the hills” to resettlement colonies. Similarly with the Baiga, who have been under strong pressure over many years to give up shifting cultivation, yet who have reacted by trying to protect forest areas against depradations by the forest department. Among the Hill Madia Gonds in Abujhmad, change has involved penetration by Maoists since the 1980s and violent counter-insurgency campaigns. Among the Sora, one result of modernisation has been the decline in the wall paintings associated with shamanism, and Vitebsky points to the irony of a shaman’s son being “trained” as an artist as a bowdlerized form of Sora painting gets put up on walls all over Bhubaneswar and Delhi.

Shamanism among India’s tribal peoples is a widespread social reality that is very little understood by anthropologists, since to comprehend what is going on the ethnographer has to know the language extremely well indeed, as well as know how everyone is related to everyone else in a community over many years, including the dead. The only book I know that can compare in this way is Madhu Ramnath’s Woodsmoke and Leafcups: Autobiographical Footnotes to the Anthropology of the Durwa (2015). Shamanic realities are the opposite end of the spectrum to academic writings. “Family constellations” is one therapeutic area where the extraordinary ways in which dead people dominate our behaviour emerges, with similar possibilities for collective healing. This is a deeply fascinating book on many levels that demands attention from the reader, and an ability to change how we think about the spirit world and meanings of modernity.

The ways in which India’s tribal cultures have changed are extraordinarily hard to encapsulate. This “nonstandard ethnography” portrays the vast extent of change among one iconic tribal group in south Odisha, the Lanjia Sora. The extent of change can be measured in three outstanding ethnographies: Elwin’s The Religion of an Indian Tribe (1955) described a world of (mostly female) shamans, elaborately terraced fields up steep, forested mountainsides, where women still wear bark-fibre cloth. Piers Vitebsky’s Dialogues with the Dead (1983) penetrated the shamanic experience much more deeply — one of the best ever books on tribal religion in India. The present volume, Living Without the Dead: Loss and Redemption in a Jungle Cosmos by the same anthropologist revisiting his field during a span of 40 years, surveys the old material in the light of this people’s overwhelming rejection of their shamanic past and acceptance of Christianity. The result is gripping and mind-bending.