Book: CROSSWINDS: NEHRU, ZHOU AND THE ANGLO-AMERICAN COMPETITION OVER CHINA

Author: Vijay Gokhale

Published by: Vintage

Price: Rs 699

Vijay Gokhale, who served as India’s foreign secretary, is one of the country’s foremost experts on China. It is fortunate, for China-watchers and the general public alike, that after his retirement, he has committed himself to writing on various aspects of China and India-China relations. This book is one more excellent product of his commitment.

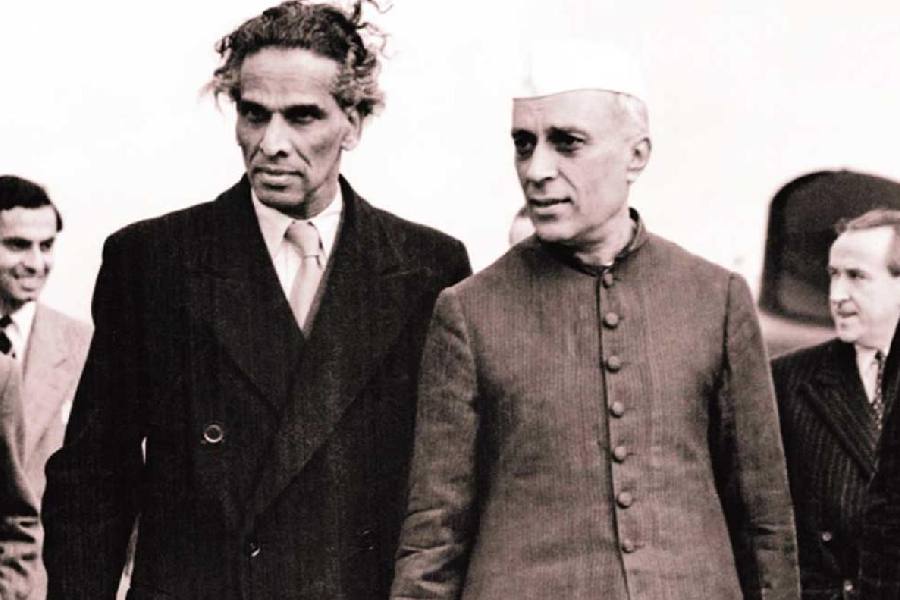

The book breaks new ground by throwing light on how Britain and the United States of America sought to use India to intercede with China and intervene in international events concerning China to secure their often conflicting interests. It also shows that Jawaharlal Nehru did not base his China policy on hard-headed assessments of its approaches and actions towards India. Instead, he focused on an unrealistic quest for Asian unity. Nehru also wanted India to be accepted as a peace-maker in a dangerous world; the British leadership, in particular, played on Nehru’s ambition.

Gokhale pursues Nehru and his principal foreign policy advisor, V.K. Krishna Menon, who repeatedly put his vanities over common sense, through four matters that involved India, China, Britain and the US. These were: one, the international diplomatic recognition of the People’s Republic of China after it had conclusively

defeated the Nationalist government, compelling the latter to retreat to Taiwan; two, India’s role in international diplomacy on developments in Indochina; three and four relate to the two grave crises over the Taiwan Strait, essentially involving the PRC,

the US and the Nationalist Chinese authorities.

Gokhale’s examination of the differing interests of Britain and the US after the Second World War in China and in parts of what is now called the Indo-Pacific region is granular and brilliantly documented. While Britain was focused on regaining its pre-War position, the US was obsessed with stopping the spread of international communism. In this, it considered that the aims of the Soviet Union and China coincided. In all the four issues probed by Gokhale, he shows that Britain wanted to use India as a card to persuade the US towards its position and often dissimulated Indian views with the US. Britain often projected India as crucial to getting ‘Asiatic’ opinion to lean towards the Anglo-American standpoint and also to act as a means to get their messages across to the Chinese side. China, too, played on India’s desire to act as a peace-maker even as it was putting facts on the ground which were completely contrary to India’s position on the Indo-China border.

The US leadership, especially the secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, comes through in Gokhale’s record as being far more sceptical about India’s role as an intermediary with China. It resisted Britain’s push for India in this respect. Nehru had little real respect for US leaders. It would have been useful if Gokhale could have gone into some detail as to how Nehru shared the British elite’s view of the ‘vulgar’ Americans who had gained global ascendency after the Second World War.

In the almost decade-long saga that Gokhale covers, he never loses the readers’ interest because of his excellent writing style. He also gets through the message that while Nehru and Krishna Menon were playing what they considered was the grand diplomatic game on the world stage, there was no attempt at analysing China’s actual outlook towards India and its geopolitical intentions. In defence of the

Indian leadership, it can only be said that it was new to

global diplomacy and inter-State relations and there were no institutional structures within the government or outside to provide it with realistic assessments.

Gokhale’s concluding ‘Epilogue’ is important for present-day policy-makers on China and on foreign policy issues in general. Gokhale argues that India’s “strategic vision” on the conditions prevailing in Asia in the aftermath of the Second World War was spot on. This is correct. But what is more important is his assertion that the vision “with regard to China, was not accompanied with actionable policy that had well-defined goals and

objectives as well as pre-identified resources and capacities to achieve them.” He rightly advocates that policy-making should be institutions-based.

Two last points: Indian policy-makers should note Gokhale’s view that the Taiwan Strait is potentially the world’s most dangerous flashpoint and that India must be wary of Britain’s increasing interest in the Indo-Pacific.