If Bhikhaiji (Cama) was the best-known Parsi revolutionary of the twentieth century, Kobad Ghandy is probably her closest 21st century counterpart. The police identified him as a politburo member of the banned Communist Party of India (Maoist); he has had around 20 criminal cases filed against him in different parts of India. His 2009 arrest in Delhi, while being treated for cancer, made headlines all over the country. As if to underline the connection, Kobad was arrested in the Bhikaji Cama complex in Delhi, named after Bhikhaiji whom the British had, of course, branded as a notorious seditionist. Kobad is accused by the authorities of being an extremist, a man who helped foment Maoist guerrilla action against the Indian State.

There are similarities between Bhikhaiji and Kobad, even if one supported a Far-Right Hindutva icon in Savarkar and the other was a Far-Left idealogue. Kobad himself acknowledged their connection. “Patriotism was the guiding force for both of us,” he acknowledged to me, “and we have much in common. Only the times and conditions were different. Marxism was and is only a tool.” As with Bhikhaiji, Kobad came from a wealthy Parsi family. But unlike her family, his backed him to the hilt. The only member of his immediate family still alive today is his sister, Mahrouk Vevaina, who has loyally stood by him and assisted him during his 10-year-long imprisonment, even though she is not a believer of his ideology. He has also had the solid support of his cousins and the Parsi community, including lawyer Fali Nariman and the Parsi journal Parsiana.

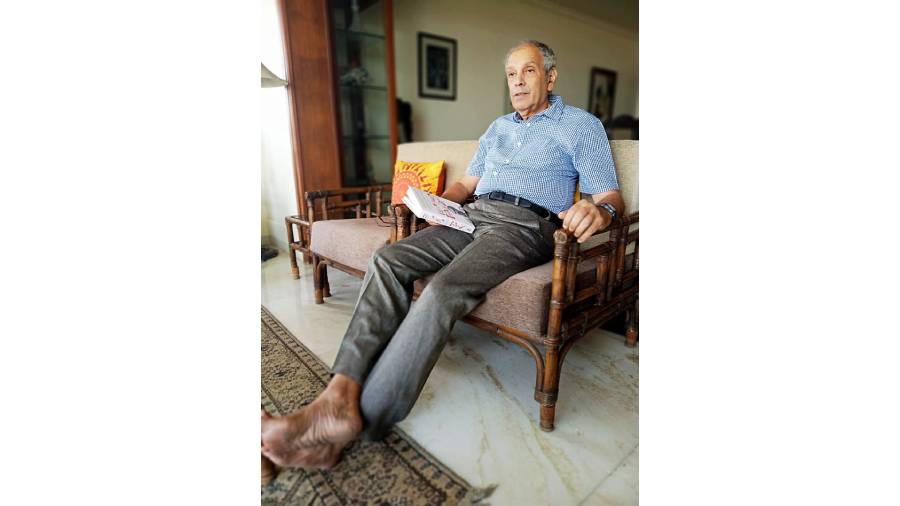

Now past 70, this tall, frail white-haired man, suffering from a multitude of ailments — prostate problems, a bad knee, slipped disc, arthritis, cervical spondylosis, irritable bowel syndrome, dysentery and fading eyesight — has been shuttled from one jail to another across the country. Though he has not been found guilty in a single case, it took him a decade to finally secure bail, with the authorities deliberately dragging their feet. Kobad was not treated as a political prisoner but housed with common criminals and there was no sympathy for his numerous significant health problems.

A man of deep conviction, discipline and dedication, Kobad explained in a letter to his Doon School friend, Gautam Vohra, that he sought comfort in little things in jail. In maintaining some human contact with his fellow prisoners, in befriending a cat or doing a bit of gardening whenever the jail authorities permitted...

When he was arrested, police officials conceded privately that Kobad has never been accused of actual violence. Asked in an interview by a journalist two years before his arrest about the use of guns by his organisation, Kobad remarked, “I can’t tell you about the armed wing, since I don’t deal with that and don’t even know their members.”...

Kobad’s life story is so romantic and idealistic that it has captured the imagination of many — the rich, educated, sophisticated man who has been rotting in prison for over a decade because of his principles. Actor Om Puri admits that his character in the film Chakravyuha in 2012 was modelled on Kobad. Adi Ghandy, Kobad’s father, was a senior executive in the multinational pharmaceutical firm Glaxo. The family lived in a large apartment on Worli Sea Face in wealthy, fashionable south Mumbai. Kobad was sent to Doon School, the country’s leading boarding school and often described as the Indian version of Eton. (He was, in fact, for a time, in class with Sanjay Gandhi.) The family owned a hotel in the hill station of Mahabaleshwar and a bungalow in another hill resort, Panchgani. The family owned an ice-cream manufacturing business Kentucky, which was famous for introducing whole pieces of fruit embedded in the cream, without the use of artificial flavours.

After graduating from St. Xavier’s College in his home city, Kobad went to London to study to be a chartered accountant. It was the 1960s and a period of great ferment among youth throughout the world. His experience in England transformed Kobad’s political outlook. He was deeply perturbed by the racism of the British, and felt that the only ones who took the issue seriously enough were various Marxist groups. He read reams of revolutionary literature and came into contact with sympathisers of the radical Left. Kobad returned to Mumbai without his accountancy degree and explained to his father that he wanted to understand his own country better. He started working in the slums of Mumbai where he met his soulmate Anuradha Shanbag. She too came from a well-to-do family that owned coffee plantations in Coorg. Her father was a lawyer in Mumbai who often handled cases pro bono for the underprivileged. Inspired by and besotted with each other, Kobad and Anuradha married in 1983. Along with some like-minded colleagues, the couple founded the Committee for Protection of Democratic Rights in the early 1970s, and were deeply involved in anti-Emergency activities. Later, the couple moved to Nagpur, where they lived in a Dalit basti. Anuradha was a sociology professor at a Nagpur college, while Kobad worked for a while as a journalist at the Hitavada newspaper. Still, their living quarters were as basic as those of their neighbours. Kobad did all the housework, while his wife went to teach. They took up the causes of tribal rights, women’s issues and Dalit empowerment. Anuradha’s brother Sunil Shanbag, a well-known theatre personality, recalls, “They were never narrow-minded ideologues, they were non-judgemental and interacted freely with people from all sections of society.”

Kobad was gentle and affectionate and never discussed revolutionary work with them. Jyoti Punwani, a journalist and close friend of Anuradha, calls them the “most unlikely revolutionaries”. She says, “They liked to have fun and were always enthusiastic. But he was deeply committed to changing the system.”

In the mid-1990s, the couple left Nagpur and decided to work full-time with tribal communities in the jungles of central India. This is when they came into contact with Maoists and had per force to go underground for fear of arrest. Now they seemed to be constantly on the run, with even their families unaware of their whereabouts. They never let the physical and mental hardships weigh them down though, despite often spending months apart. In a moving letter from prison, in 2010, Kobad recalls his wife’s “simplicity, straightforwardness and child-like innocence. Our times together were our most cherished moments”. The jungles took a heavy toll on their health. Anuradha suffered from frequent bouts of malaria and sclerosis, an auto-immune disease. In 2008, she died of cerebral malaria after developing a burning fever that could not be treated properly because she was in hiding. Kobad too had bouts of amoebic dysentery.

Though he obtained bail in all 20 of the cases filed against him in 2019, after a full decade in prison, the ailing Kobad’s ordeal is far from over. He has to make routine appearances in courts all over the country until either the charges against him are dismissed or he is convicted. His parents have died and so has his brother. But when Kobad’s parents were alive, they were proud of their son and of the causes he fought so valiantly for.

His father, indeed, gave up his corporate lifestyle, trading his fancy Mumbai flat for a simple home in Panchgani. He appreciated his son’s interpretation of the Zoroastrian prayer, that truth is the most important thing in life and truth means contributing towards the happiness of all.

Extracted with permission from The Tatas, Freddy Mercury & Other Bawas: An Intimate History of the Parsis, published by Westland Books