Book: Courting Hindustan: The Consuming Passion Of Iconic Women Performers of India

Author: Madhur Gupta

Published by: Rupa

Price: Rs 295

The absence of women artistes in the field of performing arts in India inevitably evokes debates on discrimination, decadence and disappearance. This aporia, present through different phases of history since the ancient past, has been normalised in most mainstream discourses. Madhur Gupta dives into the lives and the works of iconic women performers from antiquity through to the medieval period and into colonial and postcolonial times. Gupta’s account chronicles the dynamic lives of these women performers and situates their struggles and resistance within the cross-currents of their contemporary times.

In the Introduction, Gupta poignantly writes, “folklore, mythology and even history have always favoured male characters and the narratives we read are often not offering any scope to women who might have developed strong inroads by themselves if the focus wasn’t always on idolizing hypermasculine characters.” This observation prods readers to be sensitive to several instances of marginalisation of women performers that appear in the various retellings of our myths and legends. The domain of performing arts in a civilisation like India is shaped by oral cultures and ritualistic practices. The lives of performers, especially women, survive in collective memory as ‘remarkable’ whenever there are moments of deviation from the ‘normal’. These moments of rupture are elaborated and mythicised in a way that the women are either demonised or are restored agency through stories. The entry point of Gupta’s book is laudable in the way it gives access to the lives of women performers through the cracks of such oral stories. The author does not attempt to judge the veracity of these stories but rather presents them from the standpoint of one who glorifies and empathises with the women who chased their passions, fought against the odds, and triumphed in their own ways. The narrative presents the nuances of changing public and private cultures within which the women’s artistic selves were shaped. For instance, it reveals that in antiquity the “best looking women” would acquire the honour of nagarvadhu (town’s consort), that during the medieval period the devadasis and maharis were temple performers proficient in music and dance, that during the Mughal dynasty the tawaifs (courtesans) were masters in the artistry of tameez and tehzeeb, and that the conservative nationalistic discourses strategically marginalised the courtesans from their preserved spiritual domain that they glorified as the ghar (inner/domestic world). These observations point to an intriguing phenomenon: the performing arts and the presence/ absence of women artistes in India are tied to questions of political and cultural contests that shape an alternative understanding of Indian history.

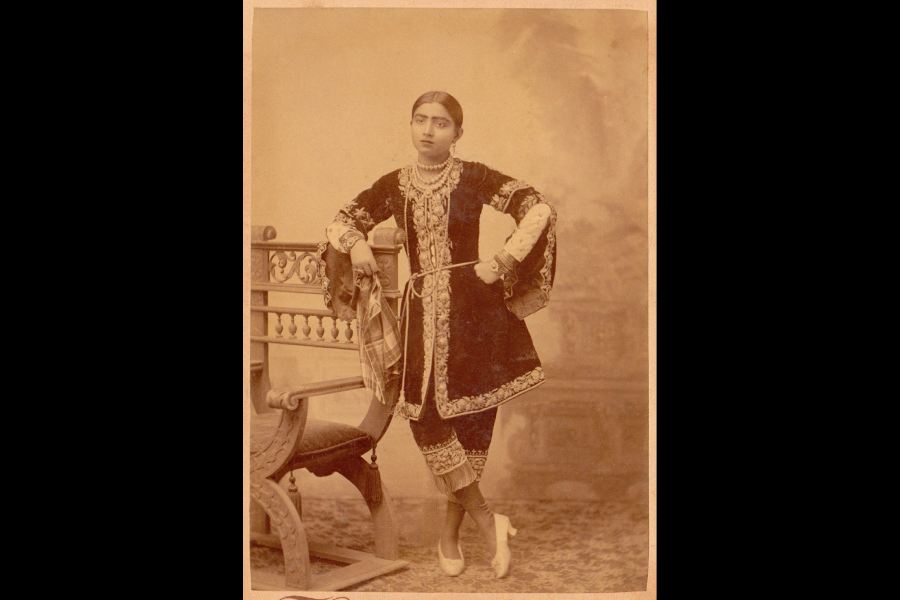

Gupta shares snippets from the lives of dynamic performers, like those of the abandonment of Roopmati, the administrative prowess of Begum Samru, the courage of Begum Hazrat Mahal, the innovative brilliance of Gauhar Jaan, the artistic, devotional strength of Balasaraswati and others. These anecdotes are engaging when read as chronicles of popular and unpopular belief but do not veer into a critical domain that can destabilise normalised versions of social history and unpack its connection to the aesthetics and the politics of performing arts.

In her essay, “The Voices of Bhaktas and Courtesans”, Vidya Rao discusses how notions of laaj, shringar and of the nayika pervade the lives and the works of women performers/courtesans as well as those of the women bhakta poets. The chronicles presented in Courting Hindustan, if read in connection with the theoretical paradigm discussed by Vidya Rao, have the potential to open up a deeper understanding of the gendered history of women performers in India.