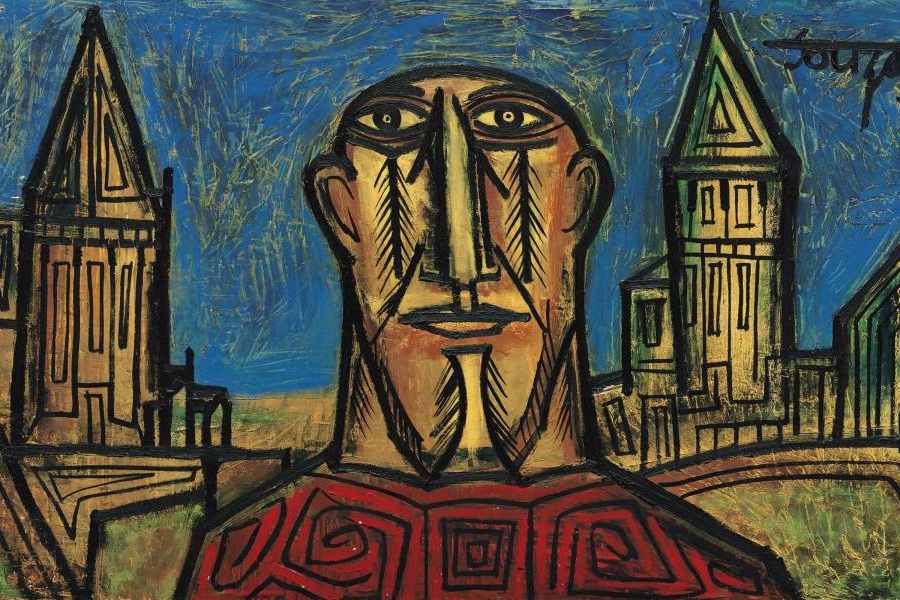

Book: F.N. SOUZA : THE ARCHETYPAL ARTIST

Author: Janeita Singh

Published by: Niyogi

Price: Rs 4500

F.N. Souza, the enfant terrible of modern Indian art, can be a divisive figure. The bold distortions of the human visage and frank exposures of the body, especially the female body, in his works can arouse strong reactions in viewers — from reverence and epiphany to revulsion and proscription. Over the course of his six-decade career, Souza experimented with a number of genres and styles, but his strong figurative practice, his line drawings, and the series of ‘black paintings’ produced in London during the mid-Nineties are instantly recognisable. What unites the various genres of his oeuvre, though, is a visceral, evocative sensuality that can be as violent as it is sexual.

It is this last aspect that is the predominant focus — at times, disproportionately so — of Janeita Singh’s book of 21 essays on Souza. Singh tries to establish Souza as a feminist artist whose explicit imagery of female sexuality made women “autonomous beings free to make their own choices regarding their identity and... privilege sexual... knowhow over sexual ignorance and exploitation...” Contrary to societies where people are obligated to one another, Souza conjures up a post-anarchist world where individuals are obligated only to themselves.

Singh’s erudition and research, both with respect to Souza and art history, are wide and deep. She seamlessly brings together fascinating threads of philosophical, religious and artistic practices in her essays to flesh out her argument and trace the unique amalgamation of inspirations that make Souza’s art stand out. Some of the diverse influences that shaped his art include South Indian bronzes, the temple sculptures of Khajuraho, as well as European modernism, especially Picasso’s art and personality. Yet, for Souza, art was “not beautiful. It [was] as ugly as a reptile.” He disturbed conventional norms of propriety and troubled social comfort by discarding the cultural canon of perfection — at Khajuraho, for instance — that tempers the shock value of the erotic expressed through art. What could have been instructive here is a parallel exploration of Souza’s well-documented homophobia, something that goes against the idea of people being “autonomous beings free to make their own choices”, in spite of working with sexually-fluid creative colleagues like Francis Bacon.

The most interesting essays are the ones that explore Souza’s world through a Jungian lens and include discussions on yogic philosophies like sankhya and tantra and the relatively-obscure philosophy of Redmondism, which had a profound impact on Souza. According to Redmondism, nature was constituted by universal elements and forces whose combinations manifested in all things and their activities. This psycho-philosophical perspective throws new light on the uneasy world of Souza’s art.

But Singh is so enamoured with her subject that she misses the bleak figure that Souza cut in the last years of his life: a man disoriented by his lack of commercial success, largely estranged from the art establishment by his own caustic tongue and effrontery. Souza, Singh writes, is a “misunderstood artist” who was “perceived as an extremely rude person, given to tempers erupting from a spirit too full of himself” owing to his “differentiated and seminal thinking”. This may be an oversimplification. Artistic genius is seldom uncomplicated and bitter realities cannot be overlooked, especially when Singh claims that her essays “are a critical study of Souza’s life and art [reviewer’s italics]”. Such is her immersion in Souza that she even writes a chapter “in Souza’s voice” — it is difficult to tell whether she lends her voice to Souza or appropriates his — where her captivation with the artist makes ‘his’ recollection of his growing up years seem somewhat self-important.

Her proximity to her subject, her veneration of Souza and the resultant narrative tone detracts from the important scholarly strands that the book brings together.