SHAKESPEARE'S BOOK: THE INTERTWINED LIVES BEHIND THE FIRST FOLIO By Chris Laoutaris,

William Collins, Rs 1, 299

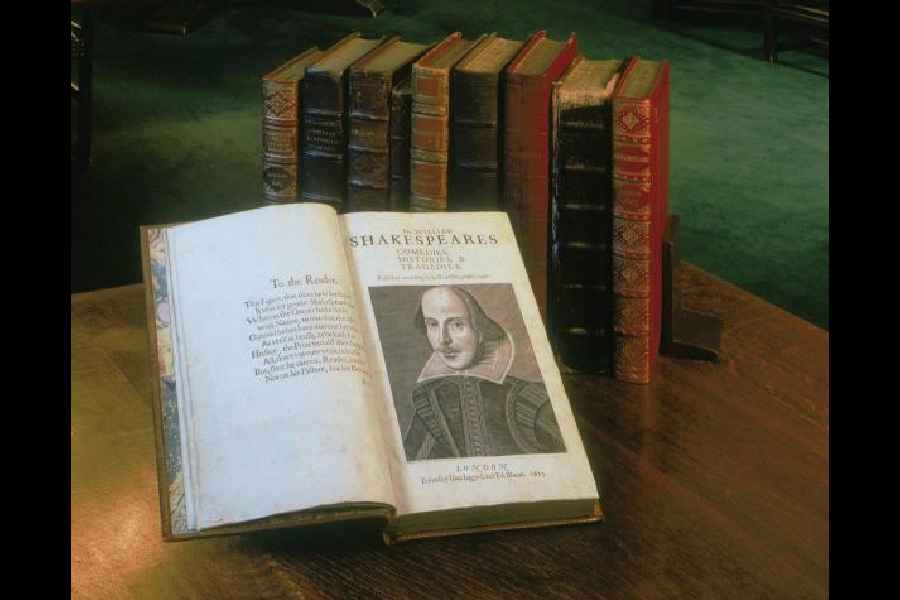

Accustomed as we are to bicentenaries or tercentenaries commemorating an author’s birth or death, we may have failed to note that this year marks the quatercentenary of the book that made Shakespeare a household name. The First Folio of 1623, a collection of thirty-six of Shakespeare’s plays in a single expensive volume (costing £1 if bound), initiated all succeeding celebrations of Shakespeare’s genius. Published by his fellow-actors and colleagues John Heminges and Henry Condell, it was printed, according to the title page, by Isaac Jaggard and Edward Blount at the Jaggards’ print-shop in London’s Barbican. The book was itself an act of commemoration, since Shakespeare had died seven years previously, in 1616. Addressing “the great Variety of Readers,” Heminges and Condell claimed to present Shakespeare’s plays “cur’d, and perfect of all their limbes, and all the rest, absolute in their numbers, as he conceived them,” rectifying the frauds and deformities of “diverse stolne, and surreptitious copies.”

This assertion of textual accuracy was less important than the fact that the Folio offered printed texts of eighteen plays for which no earlier print or manuscript version survives. Prior to its publication, only nineteen plays attributed to Shakespeare had been printed in the smaller ‘quarto’ format. Of these, Pericles, Prince of Tyre, published in 1609 under Shakespeare’s sole name, but possibly co-written with George Wilkins, was not included in the First Folio. Neither are Shakespeare’s poems, such as the Sonnets, printed in 1609 and dedicated to a mysterious ‘Mr W.H.’, or longer narrative poetry like Venus and Adonis (1593) and The Rape of Lucrece (1594). Shakespeare probably collaborated on other plays, such as Edward III (1596) and The Two Noble Kinsmen, first printed in 1634; The Book of Sir Thomas More survives in a manuscript of which three pages may be in Shakespeare’s hand.

Thus the First Folio is unlike modern editions of Shakespeare’s Complete Works, like the celebrated ‘Robben Island Shakespeare,’ acquired by Sonny Venkatarathnam and read by his fellow-inmates, notably Nelson Mandela, in South Africa’s Robben Island prison during their long incarceration. In 1875, Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay commented somewhat extravagantly on Shakespeare’s popularity in nineteenth-century Bengal: “Every home has its Shakespeare; everyone can open and read the original work.” Though the ‘original work’ was by no means a stable textual object, it was the First Folio of 1623, containing only thirty-six of Shakespeare’s thirty-seven ascribed plays, that made Shakespeare cultural property. It was material testimony to the genius of a playwright whose reputation had been sealed in performance, in the oral, visual and auditory complex of the theatre, and who appears to have been neglectful of print. In addition to the plays, the First Folio contained tributes from Shakespeare’s contemporaries (notably Ben Jonson) and an engraved portrait of the dramatist by Martin Droeshout.

Of the 750-odd printed copies of the First Folio, 235 survive in complete or partial form, 82 in the Folger Shakespeare Library. In October 2020, a copy was sold by Christie’s in New York for just under ten million dollars. Quite apart from its historical value, Shakespeare’s First Folio remains a cornerstone of the modern academic disciplines of bibliography and textual criticism, to which we were introduced as undergraduates at Presidency College by the peerless scholarship of Professor Sailendra Kumar Sen. To him we owe our early familiarity with foul papers and fair copies, gatherings and signatures, a ‘folio in sixes’, chain-lines and broken type, ‘casting off copy’, formes and quires, proof corrections and bindings, the ‘Hinman Collator’, the scrivener Ralph Crane and the near-mythical Compositor B, following up W. W. Greg’s 1955 study with Charlton Hinman’s magisterial The Printing and Proof-Reading of the First Folio of Shakespeare (1963). These are still unsurpassed, but the major studies of the First Folio’s ‘making’ and history for our present time are by Emma Smith (2015, 2016).

Chris Laoutaris does not attempt this academic exercise in Shakespeare’s Book. Rather, in an immensely readable account, concentrated into roughly four years, from 1619 to 1623, he unravels the historical events, the persons and lives, that contributed to the making of an iconic text. Particularly admirable is the way in which Laoutaris weaves incidental historical references to the Folio’s movers, makers and patrons — Heminges and Condell, their friend Richard Burbage (who died in 1619), Edward Blount, William and Isaac Jaggard, Leonard Digges, William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, James I and the ‘Spanish Match’ — into a connected historical narrative, with its own sensational ups and downs, its crises and dangers. Many links are stretched beyond credibility, but what results is a fascinating and vibrant portrait of an age and a book, with its producers, its patrons, and above all its readers, to whom Heminges and Condell addressed their famous injunction: “Buy it first.”