In a world bursting with stories, what would prompt you to write a book? And how would you know which story is yours to tell? While we might be looking for answers, Niladri Chatterjee, professor, department of English, University of Kalyani, had the answer ready. Citing Toni Morrison as the answer to what he sought to achieve through his debut novel The Scholar, he said, “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.”

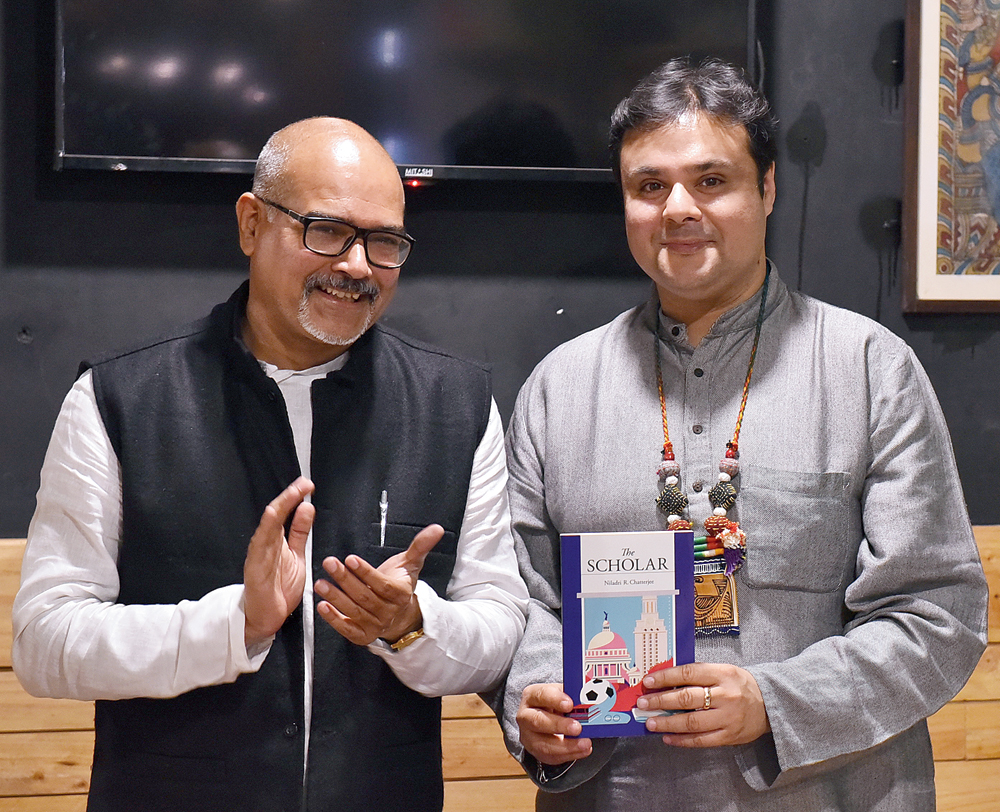

Amidst book lovers and literature enthusiasts, the book launch session of The Scholar by Niladri Chatterjee at Deshaj cafe propped up a captivating discussion on the book, brushing through aspects such as blending historical fiction with queer literature, the state of queer publication in India, the visceral role of literature in bringing two people together, re-imagining the history of a city, unbolting the sense of the term ‘scholar’ from its canonical connotation and more. The session was moderated by multi-disciplinary artiste Sujoy Prasad Chatterjee.

“When we read history, we only consume what is written in the history books without really thinking of what else was happening at that time. We don’t talk about queer publication in Indian history. This book is also my love letter to the city because Calcutta was a city that I took for granted. It was only in registering the history of the streets through the architecture some years ago, that it became a re-imagining of a past not documented in history,” said Niladri at the start of the session. Unpacking the title of the book, he widened the interpretation of the term ‘scholar’ to all those people who, like his characters in the book, live quiet anonymous lives but buy and read books for the sheer love of reading and getting transported into the lives that they would never live.

He went on to talk about how the character of Ronald Strathern was a ‘fanciful recreation’ of the British writer Christopher Isherwood and the character Sarika was drawn from Jane Austen as they shared similar worldviews of ‘matchmaking being the reason to live’. Back in the 20th century, literature served as the cipher for recognising the queer and sparking love between them. “The equivalent of Grinder in the 1900s was a particular book of poetry, Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman,” he quipped, over which queer men could connect and fall in love. The discussion steered on to the writing process of the book and the concept of research, which was more of an emotional exercise for him, transcending professional bearings. “The research was the most incredibly fun thing to do because I had to constantly look for information such as how much would a typewriter cost in 1924, how much a packet of cigarettes would cost, rate of exchange of rupee to pound, all of that as they were in 1925. The Internet was a useful map of Calcutta from 1924, where I could find all the street names mentioned. The research made the time come alive for me much more than a history book would have done,” he said. On a revelatory note, we got to know that the book was also a bibliography of sorts, having “meticulously documented all the books found on the shelves of these characters, for people to know that those works of literatures exist.”

We caught up with Niladri for a quick chat after his session. Excerpts...

How would you describe the premise of The Scholar?

It has two parallel narratives — one set in ’90s America and the other in ’20s Calcutta. It’s basically about how these two trajectories that seem to be running parallel ultimately meet. It’s also about how research, which is largely seen as a professional act, can also be seen as an emotional act, but what this book does is that it puts up the idea that research can be a journey of self-discovery, and that is what the three characters in this book do too.

What do you have to say about the state of queer literature in India?

I think it is getting better. I think that the Supreme Court verdict of September 6, 2018, has been very important psychologically, so there are a lot more queer narratives that are coming out now. But I think that they have been coming out since the 1990s but people do not know about them. I would certainly want to talk about somebody called Firdaus Kanga who published this wonderful novel called Trying To Grow, which came out in the 1990s but nobody took notice of it. There has been a lot of queer literature that has been produced, which needs to be highlighted by the mainstream media as these works are otherwise overshadowed in a way by what is being churned out by the big publishers.

Speaking of the publishing game in the context of queer publishing, how is it changing?

Well, the publishing game is changing. The publishers have become much, much more adventurous. They understand that there is a readership; a public that only wants to read interesting stories, not only heteronormative stories. The publishers are now aware that there is a market for queer narratives. A lot of queer authors can now put out their narratives as there will be publishers willing to publish their work.

A memory from the book that you cherish would be?

Oh gosh! I mean there are so many! I think it is the point where Ronald Strathern, the character from the 1920s, is walking down Cornwallis street. I think that, for me, does several things. Because I am a passionate lover of the city, I think it is my love letter to Calcutta. And, you’ve got a British person who is regarded as a colonial person but he genuinely loves the city. That’s what I would take away from the novel.

What was the genesis of the novel?

Oh, it’s a literary genesis as I came to know that in 1924, there was a Hindi writer called Pandey Bechan Sharma who was publishing stories about homosexual men in a Hindi magazine Matwala in Calcutta. This was happening in 1924! So that set me thinking as to what would it have been like to have a queer person in the 1920s, going to a bookshop, picking up these Hindi magazines and reading these short stories. So, then I began to imagine what 1920s Calcutta would have been. That was the germ of the book for me.

Literary fiction is largely considered to be weighty, one of the many elements being the big words interspersed in its language. Does The Scholar, which has been written by a scholar and a professor himself, perpetuate this perception or break away from it?

You know, I was determined to keep the language simple, so that people should be able to read it on the Metro. That was the whole idea. I wanted it to be commute reading and not heavy stuff as I felt I was targeting especially the millennial readers because I wanted them to enjoy getting lost in a time that they have no idea about, and to get lost in it through very simple English. It is written so that you can read it in a very crowded Metro train and still be able to follow the story.