Book: Planning Democracy: How a professor, an institute and an idea shaped India

Author: Nikhil Menon

Publication: Viking

Price: Rs 799

There is no shortage of scholarly literature on planning in India and its role in building an independent nation state with a unique set of features. Planning blended the Western idea of parliamentary democracy with the Soviet Union’s experiment with economic interventions by the State. The experiment of nation-building in India was, therefore, complex and fraught with difficult challenges. Nikhil Menon’s book is a new addition to this body of literature. It is important when viewed in the context of the dominant contemporary political discourse, which views the history of planning as a foolish mistake undertaken by Jawaharlal Nehru at best and an evil design at worst.

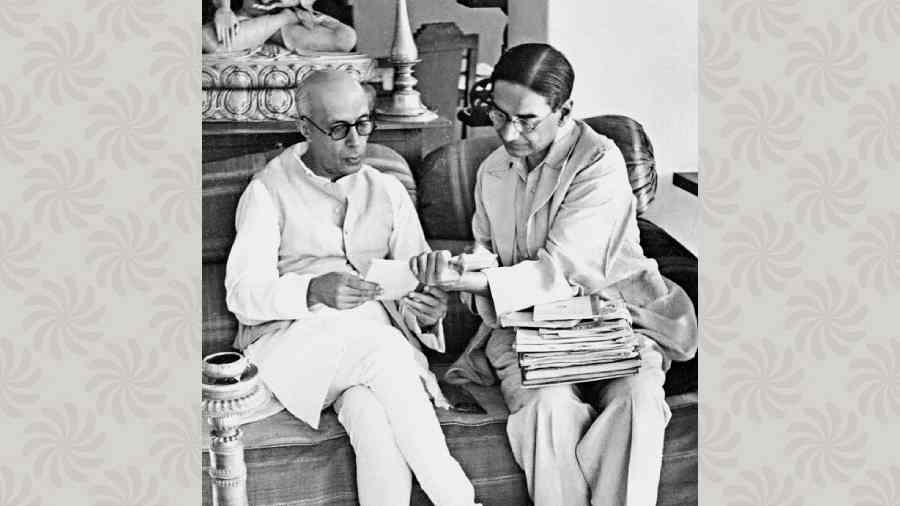

Menon attempts to view the history of economic planning in India in the context of the nation’s socio-political changes and the detailed story of its rise and fall. The book tells the story of two main characters who came from two different places: Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of India, and Professor Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, the founder of the Indian Statistical Institute and a world-renowned statistician. They did share a few things in common: the idea of a secular, pluralist India and the urgent need to initiate rapid economic development in a newly-independent colony. Even though, according to Menon, there seems to be a paucity of official documents for the period when planning was being conceived, he has been able to put together a detailed narrative of the events of the 1950s, especially the emergence of the Planning Commission of India and the putting together of a statistical infrastructure for reliable socio-economic data. Even after planning fell from political grace, the data-collection machinery was intact for many decades, one that was globally admired. Reliable data, as Menon points out, can be politically uncomfortable. During the past half-a-dozen years, India has, somewhat abruptly, become a nation with unreliable data. The Planning Commission has been shut down by the current prime minister as not (never?) being of any use.

The decade of the 1950s could be dubbed the Nehru-Mahalanobis era, with the world’s best economists involved in debates and arguments about the experiment in India. There were intellectual admirers as well as dissenting critics. The experiment caught the imagination of the world. Both Nehru and Mahalanobis were towering personalities who had tremendous influence in politics and in academia, respectively. Despite all these, economic planning did not succeed to the extent it was expected to. Some enduring questions emerged with which the nation still continues to grapple. Menon points out that these issues were important then and remain important today — the scientific-secular language of planning with a mission to create an educated and informed citizenry versus the need of using Hindu symbols for mass mobilisation and electoral advantage; the necessity for large industries with the latest technologies versus the need to look after poor farmers and create adequate employment opportunities for a growing and young population; the tension between the public sector and private enterprise.

The shift from planning to markets was not necessarily an ideological tussle or the ultimate victory of capitalism. Rather, it was a story of the requirement of planning as a tool that helped the government know more about the resources of the nation and the diversity of its people. It also helped private capital garner new-found strength and confidence bolstered by the creation of State-built infrastructure. Planning played a role in nation-building in the sense that it was used to reach out to people with a message of hope, of modernity, and of participation in national affairs. Whether it succeeded or not is a debatable question. Nevertheless, as Menon ably records, the vision to use planning was constructed on a very large framework of ideas. Any denial of the grand scale of development would not only be inaccurate but it would also be a prevarication of records and evidence — data for short.

This is exactly what is viewed with a great deal of suspicion currently. Menon tells us that the change from faith to rejection is complete, even though the fundamental problems remain. Bollywood could make a mega-budget script out of this text. There would be two heroes and one invisible villain.

As the title suggests, planning was not merely an instrument for building material prosperity; it was also about creating a new democracy in India. Planning constituted a very serious attempt at building the foundations of the idea of a secular, pluralist and prosperous India, an idea that is currently under severe attack. Menon’s book is well worth the reading to help distinguish fact from fiction given the current discourse on the idea of India.