Book: A history of water: Being an account of a murder, an epic and two visions of global history

Author: Edward Wilson-Lee

Publisher: William Collins

Price: £25

A monastery murder mystery unsolved for four centuries. A talented jailbird who died a pauper but posthumously became modern Europe’s most celebrated epic poet, and is definitely one of the finest poets of the sea. And a Portuguese court official, diplomat and intellectual who embraced the breadth of the world that maritime exploration was opening up, became the chronicler of the age of Vasco da Gama and Pedro Álvares Cabral, but died a heretic, stripped of wealth and liberty. He was either strangled or burned, at home or in an inn. He exists only in documents in the national archive which he once headed, while Camões is in every good bookshop. Who killed him? Which thread of this Rashomon tale is true, and does it matter?

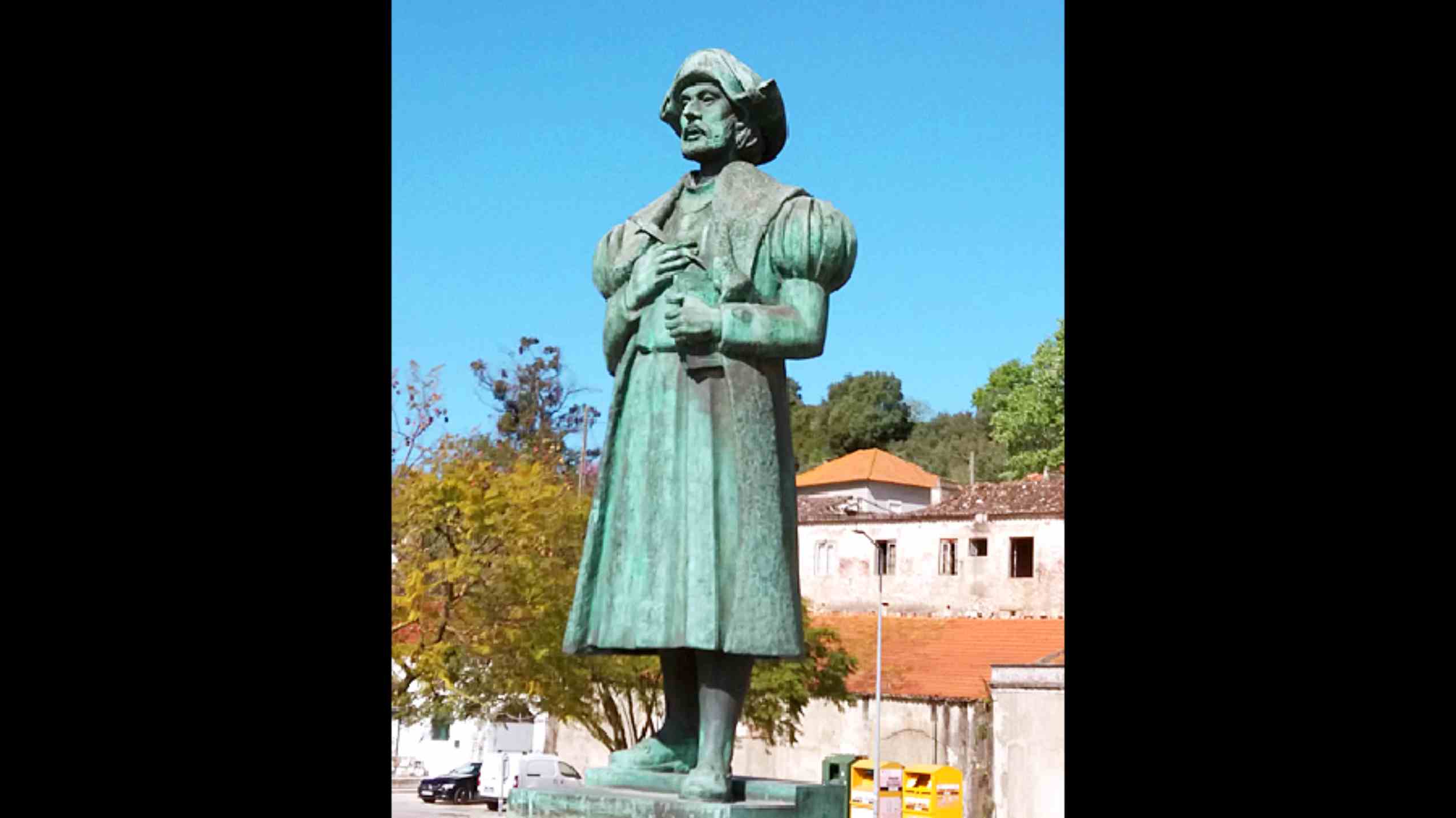

The Cambridge academic, Edward Wilson-Lee, whose interest is the history of the book, teases out the threads — the lives of Luís Vaz de Camões (1524-1580, born the year Vasco da Gama died in Kochi), a vagabond all his life and Portugal’s national poet after The Lusiads were translated, and his contemporary, Damião de Góis (1502-1574), scholar, art collector, protege of Erasmus, guest of Martin Luther, friend of Albrecht Dürer, familiar figure at royal courts and the universities of Leuven and Padua, and keeper of Portugal’s national archive. Camões stole the limelight and achieved world fame, admired by Hermann Melville and Sir Richard Burton. But this book is really about Damião, who was charged with heresy and suffered an unnatural death in obscurity — even the date on his gravestone was wrong, and no one cared.

They reacted differently to the age of exploration, which Portugal spearheaded. Damião was inspired as the borders of knowledge widened, and he produced literature on pre-Christian Lapps and Ethiopian Christianity. The latter was a pan-European fascination — Prester John, the mythical Christian monarch of the East who wrote to the Byzantine emperor in the 12th century, was later surmised to be in Africa, though the origin of the fiction may actually lie in the Asian Nestorian tradition. And the motives for Vasco da Gama’s voyage to Kerala were famously ‘for pepper and Christ’. The latter referred to the kingdom of Prester John, presumed to be in Africa or India.

But Damião was struck not by the myth of exotic lost Christians but the reality that people everywhere are essentially similar. He anticipated the humanism that is the bedrock of the 20th-century system of universal rights. Wilson-Lee suggests that though Portugal maintained a “conspiracy of silence” about its voyages to protect its monopolies, Damião anonymously leaked his writings, and a Latin translation drove Montaigne to the crucial conclusion that humans were not significantly different from animals, though Christianity gives them special status.

The 16th century shook the very foundations of Europe, especially Iberia, which took the lead at sea. The continent’s clerics had laboured through the medieval period to sustain a geocentric and anthropocentric myth of uniqueness and manifest destiny. Even 20 years after the death of Camões, Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake for speculating that the sun is just another star. And yet, every trading ship that returned from the East brought back more evidence that there was nothing special about Portugal or Europe. In fact, by the reckoning of Indians, who have elevated bathing to the level of ritual and sacrament, the Portuguese stank.

Humiliatingly, it was clear that the Portuguese were not pioneers either. The sea lanes they sailed all the way to Japan were made superhighways long before the Christian era by Arabs, Gujaratis, Cholas, Kalingas and the Chinese — Zheng He’s fleets in the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea, the size of floating cities, dwarfed Portuguese shipping.

The Portuguese navigators were just heavily armed traders, not the heroic figures that we learn about in school history texts, even now.

Wilson-Lee attributes the popularity of Camões to a partial erasure of reality, which reassured the Portuguese that their project remained credible. He presented Vasco da Gama as a Homeric hero battling the cruel sea and cunning primitive races. In reality, of course, his telling preserved xenophobic, supremacist, Eurocentric myths by erasing confusing details about the modernity of the East.

Damião, meanwhile, fell victim to that very xenophobia. He faced the Inquisition on charges which included listening to imported polyphonic music, owning the hair-raising art of Hieronymus Bosch, visiting Protestants and studying other cultures like an anthropologist would but not denouncing them as a Catholic should. But was his death an extrajudicial execution conducted by one of the founders of a prominent Christian order, whom Camões perhaps knew as a Lisbon thug in his delinquent youth? At this point, Damião’s national archive fails to be definitive, and the Rashomon effect wins.