I am yet to read Laura Dassow Walls’s acclaimed 2017 biography of Henry David Thoreau. But from what I have been able to gather, it is kin to Ramachandra Guha’s Gandhi 1914-1948.

Both books are incredible — for our times. For the reason that both those men seem to belong to another time, a different planet.

Thoreau’s essay, Civil Disobedience, I am sure, does not find place in Donald Trump’s bookshelf. He will just not be able to comprehend the author of Walden saying, “Under a government which imprisons any unjustly, the true place for a just man is also a prison.”

Gandhi’s appeal for Hindu-Muslim peace, signed with Jinnah, in the summer of 1947, would likewise not be part of Narendra Modi’s favourite reading. He would just not relate to the appeal’s statement: “We denounce for all time the use of force to achieve political ends”. Turkey’s supremo Recep Erdogan, Philippines’s Rodrigo Duterte and Australia’s Scott Morrison would not either. And Aung San Suu Kyi? Not first State Counsellor of Myanmar, Daw Suu. Mahinda Rajapaksa, standing with chest turned out and stomach tucked in, at power’s doorstep in Colombo, would not have time for it at all.

Gandhi is far too idealistic for them all — Hindu, Muslim, Pentecostal, Roman Catholic, Theravada Buddhist. Altogether too humane.

But this is not just about political leaders, or individuals. It is, as I said, about our times. A growing sentiment is responding to majoritarian intolerance of difference, of variation, accommodation, sanctuary. Also, therefore, of indifference to civil liberty, human rights. And it is turning to the supremacist as hero.

Strength, not justice and power, not veracity, are the new gods.

Gandhi by M F Husain M F Husain

While other books will tell us, for instance, of a typical Gandhi fast by its political or philosophical ‘reason’, its duration, its agonized inching towards termination, Guha will tell us of the fast’s more mundane trigger. For instance, that his 1918 fast for the Ahmedabad mill-workers came after he heard what was literally bazaar gossip to the effect that Gandhi has a car to go about in, eats “sumptuous food” while the striking mill-hands suffer. And it is this that stung him into the fast. Not an unknown factoid this, but an unnoticed one.

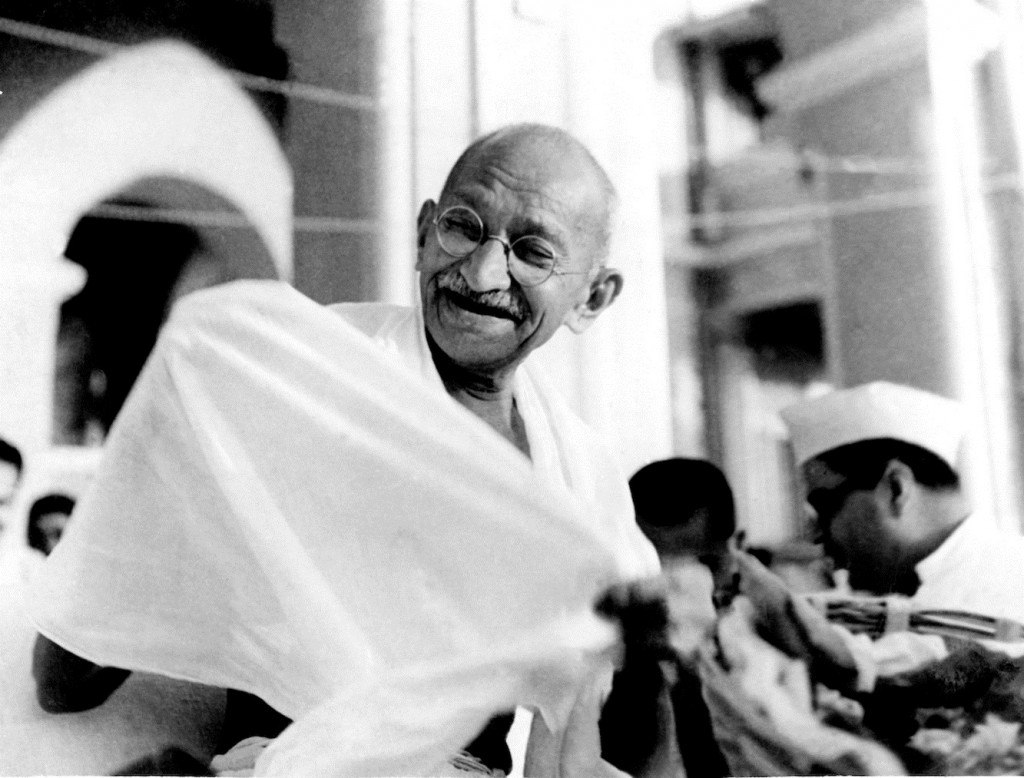

Similarly, great accounts of the Dandi March in 1930, like that vivified in Thomas Weber’s On The Salt March, have re-enacted that iconic event. But Guha’s tracking down “an eyewitness” account converts the known depiction into a moving footage: “It was a quick pace between running and walking… The breathless walk made you see how urgent and downright and final was his call… He did not tarry for the roadside honours… He passed on after a lady had placed a kumkum on his forehead…”

Diaries and letters of policemen, civil servants, governors are Guha’s preferred sources of insight. And persons like Gandhi’s one-time typist, R.P. Parasuram. For Guha, the hero lives in the detail. He has mastered a method, a sociologist’s and anthropologist’s perhaps. It is this: if you see a document or a photograph, capture its central image but thereafter let its margins, its edges, often frayed and crumpled, open to you another story.

And this is hugely rewarding.

Gandhi’s talks with Governor Casey in Calcutta in 1945 are well-documented but not quite so the fact that when Gandhi left the governor’s mansion, 150 of the liveried attendants, Hindu and Muslim, thronged to salaam him (as recorded by Casey).

The assassination and funeral are, now, lore. Pyarelal has taken us through them in The Last Phase and Rajmohan Gandhi has described them with the deeply moving intonations of a Greek tragedy in his biography, Mohandas. From Guha we get not just the burnt crimson of that moment but all the deepening tinctures that drowned with that setting sun. We get the make of the cortège-van, the name of its driver. And a vignette of the assassin in the police station, bleeding from the crowd’s spontaneous mauling of him. The best of narrations can sometimes miss a step. Guha has ‘Abha’ for ‘Manu’ in his description of the grand-niece who was pushed down violently by Godse seconds before he fired from his Beretta. But that does not take away from the magnetic charge of the account.

Guha’s word-sketches of the figures, whether famous or scarcely known, with whom Gandhi lived and worked comprise the book’s strength. Jinnah and Ambedkar come alive, not at a counter-helm but on the same deck as the main passenger. And with them, the great contestations of Hindustan, no less frenzied now than when Gandhi lived.

And with him gone.

Gandhi: The Years That Changed The World — 1914-1948 By Ramachandra Guha, Allen Lane, Rs 999

In times such as these, for a new biography of Gandhi to have appeared at all and then to have received discerning appreciation the world over is extraordinary. In fact, it is incredible.

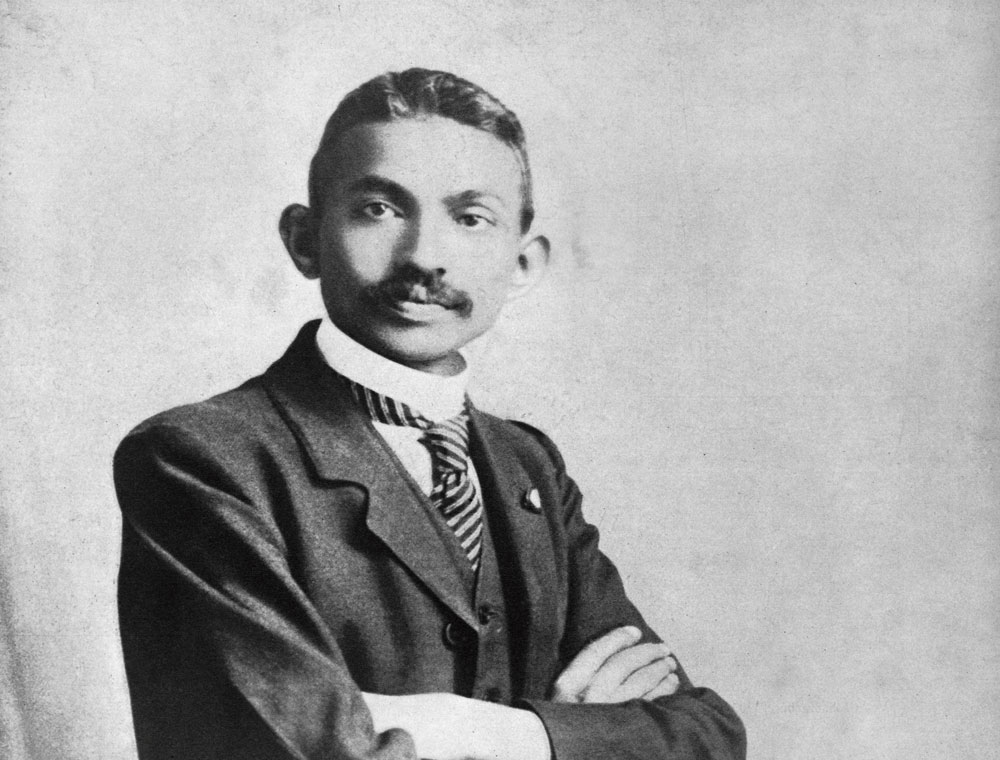

And yet Ramachandra Guha shows in his riveting biography that it is precisely in being out-of-tune, out-of-joint with this 21st century of real and surreal inhumanities, that Gandhi’s un-dimming appeal lies. He continues to do in an afterlife opera what he did all his working life: stun by difference.

Guha captures the paradoxical, enigmatic, contrarian Gandhi in his biography brilliantly. And he does so in his own hallmark biographer’s style. That is, he goes not by the mastheads of Gandhi’s life, not by the ‘Gandhi era’ headlines, but by the sub-masts, the sub-headers and the fine-font small-typeface details on which the big captions stand.