In 1954, the American psychiatrist, Fredric Wertham, emerged as a mighty adversary to the comic book industry with the publication of Seduction of the Innocent. As strange as it may seem today to fans of Superman or Batman, Wertham held comics to be responsible for corrupting young minds by creating an “atmosphere of cruelty and deceit”. Post-war America was obsessed with the problem of juvenile delinquency; so much so that the crusade against comic books was spearheaded by a subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Committee. Soon, publishers found themselves vilified as censorship laws pushed for the ‘triumph of good over evil’.

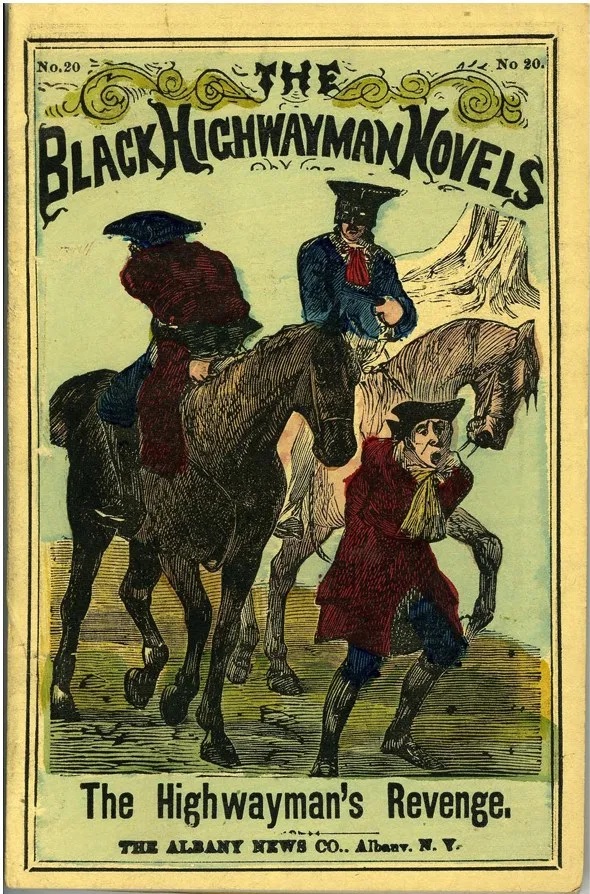

This was, however, not the first time that literature aimed at young minds had sparked such a debate. Across the pond, in the 19th century, a publishing phenomenon known as ‘penny dreadful’ — penny blood — had fascinated schoolboys, most of whom came from working-class families and had been taught to read at State-funded schools. Penny dreadfuls were cheap, sensational and often lurid, telling stories of nefarious highwaymen: Gentleman Jack being an example.

Significantly, the Victorian obsession with the impact of the macabre on children intensified with the rise in juvenile crime. Juries linked the murder of a woman in East London by her two young sons to cheap literature; the verdict on the death of a 12-year-old in Brighton was declared to be “suicide during temporary insanity, induced by reading trashy novels”. Decades later, two homicides in Canada were attributed to comics.

Whether exposure to violent media can be held responsible for aggression in children remains a contentious issue. But that has not stopped the minders of morality from banning books. Dime novels depicting violence and gore are not the only kinds of literature to attract such ire. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was banned for much of the 20th century, prompting C.S. Lewis to pen a defence of fantasy stories in 1952.

Censorship continues to plague modern literature. Consequently, the list of what is considered ‘appropriate’ for children has only shrunk. When And Tango Makes Three, a book about two male penguins raising a baby, is banned, it sends out a clear message of a perverse morality at play: the target here is not explicit violence but an alternative family structure.

Comic books may no longer attract censorship the way they did before, but children’s literature is a conservative domain. Why else would libraries shun stories like Wonder, The Seventh Wish or George, that touch upon the complexities of young lives yet rarely find representation on the shelves of mainstream literature? The suppression of literary ideas that go against the prevalent tide of morality is, ironically, a manifestation of a violence that is latent.