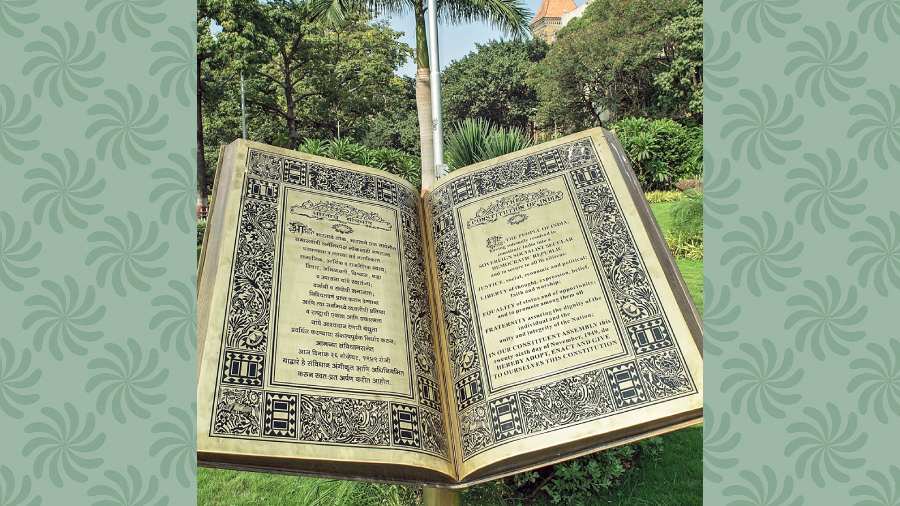

Book: Liberty After Freedom: A History Of Article 21, Due Process And The Constitution Of India

Author: Rohan J. Alva

Publisher: HarperCollins India

Price: Rs 599

Of the different vantage points from which one can examine the relationship between law and language, the historian’s perspective has special significance. Words in laws have immediate power over the conditions of our lives. The immediacy of this power means that individuals have more at stake in the meanings of such terms. This is why some legal scholars and judges insist that the original understanding behind a legal term should serve as an anchor against motivated attempts to distort a law’s effect. If laws are changed by amendment, how can they be modified through semantic trickery in court? A historian of law is in a special position to interrogate these concerns.

Rohan J. Alva’s Liberty After Freedom enquires into the fascinating history of one such instance of changed meaning: the fate of “due process” in Article 21 of the Constitution. Students of constitutional law are familiar with the peculiar problem that the provision has raised since 1950. The provision states that “No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.” So far as legal rules go, the stakes cannot get higher than Article 21. And, yet, the provision seems to allow for life and liberty to be taken as long as a law authorizes it. As it happens, the Constituent Assembly almost put in place a much stronger protection that would have prevented life and liberty from being restricted without “due process of law”, a term that supposedly requires fair procedures and strong justifications from government measures. The Constituent Assembly considered “due process” and rejected it in favour of the feeble phrasing that Article 21 currently has.

So, if the framers explicitly chose not to have a “due process” clause, shouldn’t we respect that choice? This is the question Alva grapples with. His central argument is that concern for the framers’ intentions should not restrict us from adopting “due process” because their intentions were unclear and inconsistent. To support his claim, he takes us on a journey through the many rounds of drafting that Article 21 went through before it took its current form, marking out the different individuals and events that played a role in what is arguably the Constitution’s gravest flaw. Alva’s presentation of the proceedings of the Assembly allows us a rare glimpse into the full arc of a single provision’s evolution. Key parts of his argument include his portrayal of the unexplained disappearance of the phrase, “due process”, during the drafting, inconsistencies in the explanations provided by the Drafting Committee, the Committee’s deviations from the Assembly’s decisions, and infirmities in the framing of provisions related to arrest, detention, and property. Alva’s investigation reveals the limits of speculating on the motivations of the drafters and the understanding of the members of the Assembly regarding the implications of the drafting choices they voted on.

Regardless of how one feels about the vagaries of a concept like “due process”, the book provides a compelling argument against obsessing over the original intent of the Constitution’s framers, urging us instead to imagine novel ways in which to limit government excesses while maintaining judicial accountability.