Book: The Vagabond Princess: The Great Adventures of Gulbadan

Author: Ruby Lal

Published by: Juggernaut

Price: Rs 699

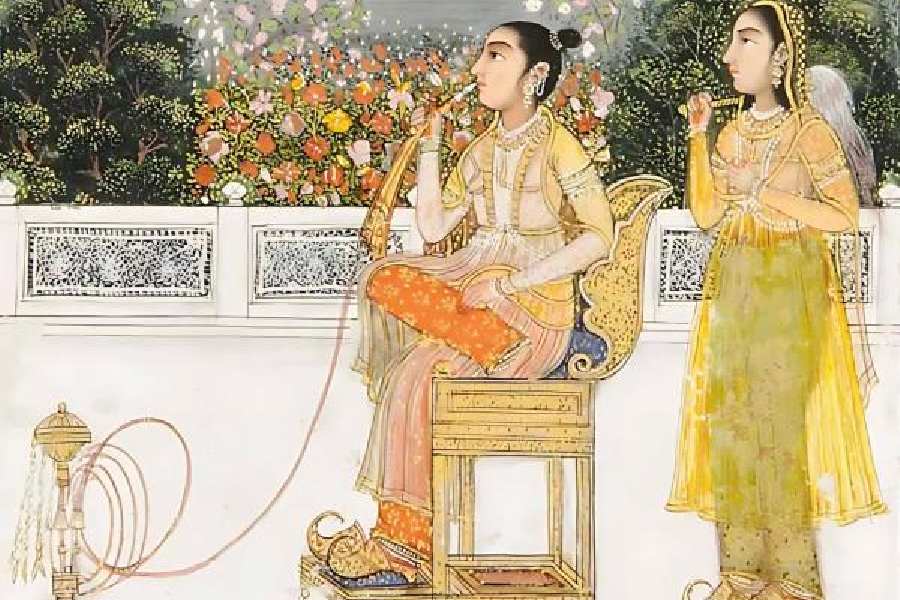

Ruby Lal’s meticulous reconstruction of the life of Gulbadan Begum (1523-1603), the daughter of Humayun and the author of the first ‘unofficial history’ of his reign, is more than a scholarly accomplishment. It’s a passionate feminist reclamation of the life of a remarkable Mughal princess who was condemned to remain in the footnotes of official and academic histories. Even when Gulbadan Begam’s Ahval-i-Humayun Badshah was translated by Annette Beveridge in 1902, her image continued to be that of a clichéd Mughal matriarch who remained confined within the Mughal harem and wrote a “little history” of her father’s reign. Lal’s project was triggered not only by Beveridge’s cavalier treatment of Gulbadan’s history but also by the several missing pages from her book that held possibilities of knowing other, intriguing aspects of Gulbadan’s life and letters.

Lal’s archival pursuit led her to read the original manuscript of Gulbadan’s historical work, now in the reserves of the British Library. Her intimate reading of Gulbadan’s manuscript generated new insights into Gulbadan’s historical sensibilities, her prose style and, above all, the descriptive richness of its narrative. But Lal, like Beveridge before her, was stumped by the book’s missing pages. She knew Gulbadan had undertaken an audacious pilgrimage to Mecca years before she wrote her book, but there was nothing in the manuscript that spoke of it, or even if it did, those pages had mysteriously disappeared. Long years of research on Gulbadan that began even before Lal wrote her biography of the Mughal empress, Nur Jehan, yielded a critical episode in Gulbadan’s life that radically recast her image from a stoic matriarch to an intrepid adventurer who defied convention to first, undertake a pilgrimage to Mecca and, then, break away from the official entourage to embark on a deeply personal quest of faith, wisdom and identity.

It is then the two ‘disappearing acts’ in the life of Gulbadan Begum, that of her sudden decampment from the royal entourage in Mecca and her forced return to Agra four years later and the equally bewildering ‘disappearance’ of those pages from her manuscript that may have described that episode, that frame Lal’s reconstruction of her life.

Lal tries to connect two defining episodes of Gulbadan’s life, her writing of a history of her father’s reign and her journey to Mecca, by placing these not only in the immediate context of the life and the times of the Mughals in India under Babur, Humayun and Akbar but also within a much wider cultural history of Islam in West Asia.

She also places Gulbadan within a genealogy of Muslim women of valour, spirituality and scholarship. Gulbadan may have been a Mughal princess, but her inner world had transcended the boundaries of court and empire. Her scholarly pursuits and her spiritual wanderings were not just reflections of the mobile life she lived as a child or the close relationships she enjoyed with pious matriarchs in her family but were also products of her imaginative kinship with Arab princesses, mystics and philanthropists like El Qutlugh, Zubaida and Fatima, the youngest daughter of the Prophet, from whom she learnt a “theologically grounded empathic conception of Islam.”

The book’s first half reconstructs Gulbadan’s childhood in Kabul, her peripatetic life in tents and caravans, and the protective circle of male and female guardians who nurtured her. It then draws upon her historical account to offer an intimate peek into the royal household in all its ethnographic detail of courtly life, people, places, domestic life, of royal manners and quirks, and of her own father. The second half of the book sees her confined within the women’s quarters of Fatehpur Sikri in Agra under the watchful eye of her nephew, Akbar. It is this half of the book that takes readers into Gulbadan’s pilgrimage to Mecca and to her inexplicable ‘disappearance’ soon after.

Ruby Lal crafts her biography of Gulbadan as a work taking shape in those archival traces that began to connect in unexpected ways. The Vagabond Princess thus emerges as a book that lays bare the tenuous processes of its own making. It invites historians and readers into a serendipitous archival quest and offers new ways of writing history in a self-reflexive mode. There is perhaps no better way of reclaiming the lives of women from the disregard of the historical record.