Book: From Dasarajna to Kurukshetra: making of a historical tradition

Author: Kanad Sinha

Publisher: Oxford

Price: Rs1,795

Kanad Sinha’s Dasarajna to Kurukshetra is an ambitious and scholarly exposition on the making of an ancient Indian historical tradition. It focuses on the epic, the Mahabharata, subjecting it to a very close reading alongside the rich commentaries that mark recent and older scholarship on the text. Sinha does not ascribe to the epic the status of history but is attentive to its enormous potential in indexing change and transformation and in creating archetypal heroes whose ideational significance persisted over time and space. It is not an easy read; it synthesizes rich and dense scholarship on the subject of the epic and its reworking and, in the process, comes up with a very magisterial treatment of the text and its context.

Whether ancient Indians had history or historical consciousness of the kind we associate typically with European Enlightenment precepts is not a new debate or concern among historians and scholars. Recent scholarship has drawn our attention to the historical mindedness of Indian society and even argued that the existence of diverse genres with multiple literary and performative functions were part of the subcontinent’s rich historical tradition and its distinctive mode of recalling, remembering and commemorating. While Sinha does not actively engage with this scholarship on what was history in the ancient past, he comes up with a meticulous attempt to contextualize the epic and analyse its continual reworking so as to align it to a society, which was in the throes of continual transition.

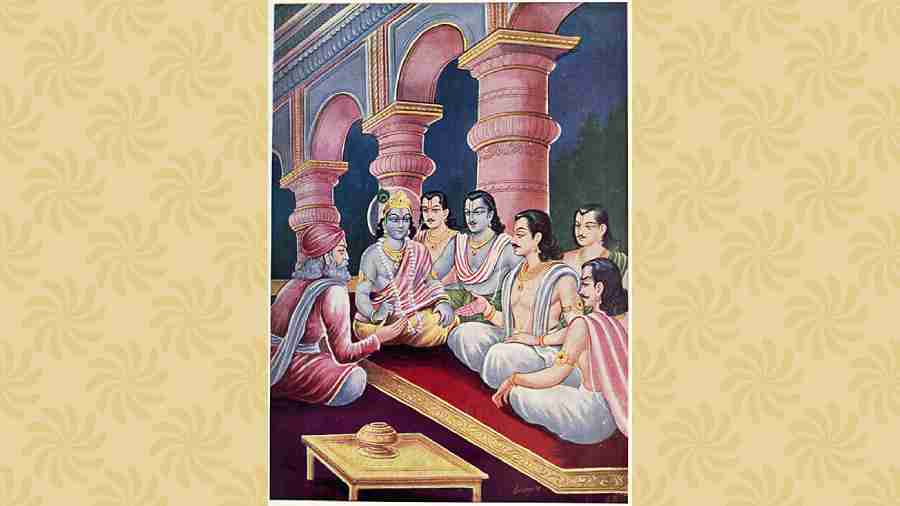

The Mahabharata originated as an itihasa of the later Vedic Kuru clan. Sinha reads the epic taking recourse to existing scholarship to comment on the socio-political landscape of later Vedic India when the varna system was being institutionalized and there were voices of dissent against rites and rituals. What is especially compelling is the way archetypal heroes and villains were being constructed — the villainous Duryodhana, a tragic anti-hero who was a good kshatriya and demanded his birthright and whose moment of death was accompanied by a cosmic display of winds and meteors. There was, on the other hand, Karna, a typical Indo-European hero who, like Achilles, had power but lacked status. According to Sinha, he was perhaps a transitional hero straddling two eras. With Krishna or Vasudeva Krishna, the reading gets even more complex as the author locates him in the epic. A figure who apparently had no link with the kingdoms of Kuru-Panchala, he appears on several occasions and, yet, is difficult to anchor. Sinha sums up the views of scholars about the enigma that Krishna was in relation to the epic and suggests that it is not his intention to establish the historicity of Krishna but to analyse the various sources, which are useful in studying the character of Vasudeva Krishna. The interpretation is replete with details and does not make for easy reading but definitely establishes the multi-layered nature of the epic that can be located in the later-Vedic period.

The book carries the signs of expertise and scholarship. However, it is not easily accessible and it requires careful navigation to identify the broad formulations that the author chooses to make. These include the ways in which the epic was brahmanized at the cost of other elements. All bardic traditions were compiled and standardized and brahmanized and the Mahabharata was no exception. This was not true of the Ramayana which the author argues was not an itihasa, not even a Purana but a kavya. What remains unclear in Sinha’s account is the nature of protocols one associates with itihasa and whether these could be examined and scrutinized outside the reading of the characters of the text. The concluding section of the book offers a useful synthesis of the arguments about the later Vedic context of the epic, how political and social convulsions were reflected in the epic that stood out as the itihasa of the age. This is not to say that the figures were real or the events happened exactly the way we read them but to affirm that the text gives us a key to the genealogical crisis among tribes, succession struggles that stood as proxy for competing ideas. The same text was transformed again and again until it was rendered a scriptural value that endures even today