Book: A Private Spy: The letters of John Le Carré

Edited by Tim Cornwel

Publisher: Viking

Price: ₹999

John le Carré, or David Cornwell, wrote under a pseudonym and made a career of secrecy for much of his life as a professional spy. But his personal history furnished material for at least four of his books: The Naïve and Sentimental Lover (1971), A Perfect Spy (1986), Single & Single (1999) and The Pigeon Tunnel (2016). His official biography (2015) was published during his lifetime by Adam Sisman, and his affair with Susan Kennaway, wife of his friend, James Kennaway, is described not only in the latter’s novel, Some Gorgeous Accident (1967), but also in the posthumous The Kennaway Papers (1981). Still, le Carré’s death in 2020 has released what promises to be a steady stream of books dealing with a life paradoxically signposted as ‘private’ or ‘secret’. The present volume, a collection of his letters edited within a narrative framework by le Carré’s son, Tim, does not mention one of le Carré’s numerous lovers, Sue [Suleika] Dawson, whose tell-all book, The Secret Heart: John le Carré: An Intimate Memoir, also appeared in 2022. Meanwhile, Adam Sisman has scheduled a follow-up to the authorised biography, to be released later this year under the title, The Secret Life of John le Carré, revealing ‘a hidden life of secrecy, passion and betrayal.’

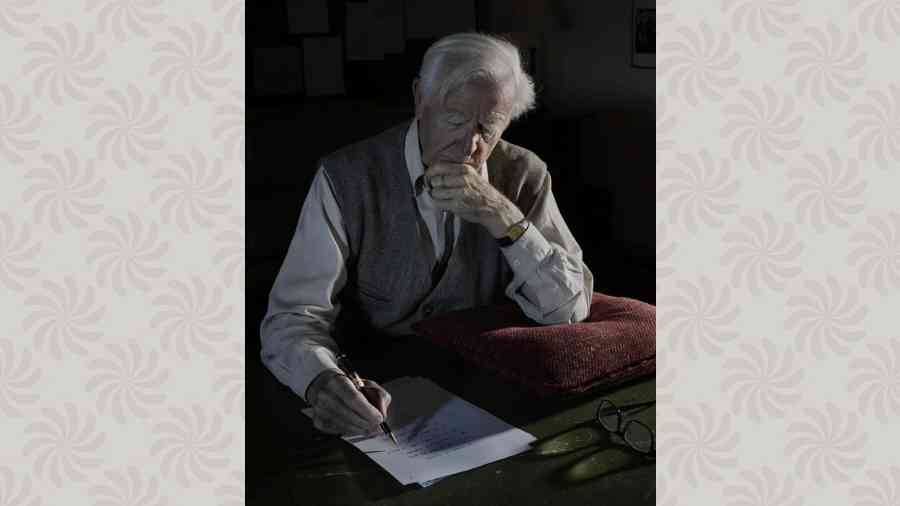

Not much can remain secret, surely, in a life so exhaustively, even forensically, documented. As le Carré himself demonstrated in a form that he made his own, secrecy in the espionage novel is the uneasy twin of surveillance. Writing to his correspondents — family, friends, agents, admirers, lovers — in scrupulous longhand, le Carré knew that his letters would be “treasured, archived, potentially publicised, misused, misquoted or sold.” His correspondence, now destined for the Bodleian Library in Oxford, was archived by his wife, Jane, and his secretaries; his first wife, Ann, kept all his letters over a period of two decades. But much was destroyed; le Carré himself burnt the papers of his father, the conman Ronnie Cornwell, after his death in 1975, thus removing from public examination the details of a father-son relationship that has assumed the proportions of myth. A Private Spy contains only one letter to Ronnie, but many to his stepmother, Jeannie, and his mother, Olive, who abandoned him when he was five, walking out on an abusive husband. Le Carré also burned the letters he wrote to his first American publisher, John Geoghegan; those sent to his agent, Rainer Heumann, and his close friends, John Miller and Yvette Pierpaoli, were destroyed by their heirs.

Still, there is enough material here to absorb the reader, beautifully curated by Tim Cornwell, who died suddenly in 2022, and interspersed with rare archival photographs. The letters give substance, warmth, brilliance and intimacy to a remarkable life: le Carré’s schooldays at Sherborne School, leaving at the age of sixteen to spend a year in Bern; his lifelong love-affair with German culture (reflected in his fictional spy, George Smiley) and his induction into the British intelligence services; the undergraduate years at Oxford and becoming a schoolmaster at Eton, of which he wrote, “I don’t think I’ve ever met so much arrogance … the boys are collectively quite frightful.” In 1958, le Carré formally joined MI5; two years later, he was posted at the British embassy in Bonn as an agent of MI6. The Spy who Came in from the Cold, published in 1963, changed le Carré’s life and Cold War fiction forever. In May 1966, le Carré wrote an open letter to the Moscow Literary Gazette, stating that “there is no victory and no virtue in the Cold War, only a condition of human illness and a political misery.”

Even after the end of the Cold War, le Carré remained convinced of human illness and political misery in the largest sense. Timothy Cornwell has chosen to group most of the letters around the publication of his father’s major novels, thus building a chronology that relates the life closely to the work. This progression enables us to see the issues that continue to preoccupy le Carré as man and writer: individual goodness and love as ineffectual against greed, hypocrisy, fascism, capitalism, and the moral hollowness of politicians. Late in life, he bitterly reviles the folly of Brexit and the “far-right Trumpists” governing Britain. “Putin is appointing himself Ruler for Life, so we look like having a pretty awful decade,” he writes on February 8, 2020, lamenting the absence of resistance: “where do we sign up?” This question, of course, remained unanswered. Even as he approaches death — “a very private matter” — the letters reveal an intensely private man with intensely public concerns, a life divided between friends, family, lovers on the one hand, and writing, craft, and the world’s ills, on the other.