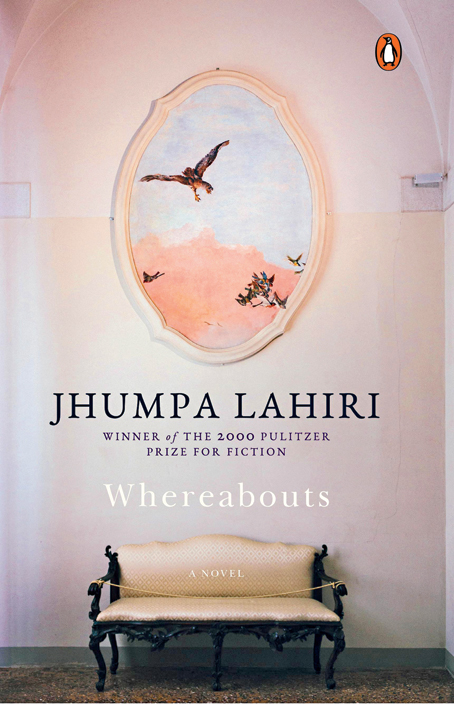

In the short story In Spring from Jhumpa Lahiri’s latest collection titled Whereabouts (Penguin; Rs 499), the narrator muses “I dislike waking up and feeling pushed inevitably forward” resonating deep with a nihilistic mind that feels similarly about life. There are 46 sections of varying lengths, never more than five pages strung together under a peach and beige cover that has an empty and inviting couch on it, which is a departure from the cover of the original book Dove mi trovo which the author herself translated to English from Italian.

The narrator’s despondent vignettes of her life reveal little of her material world. We know she is an academic and teacher of age 46 who lives alone in Italy, grappling with the comfort and malaise of an isolated existence. She does have friends she occasionally spends her time with but her only companion are the thoughts in her head.

The Indian American identity that Lahiri has struggled with and portrayed repeatedly in all her works –– The Namesake, Lowlands, Interpreter of Maladies and Unaccustomed Earth –– is missing from this collection. However, the author’s struggles with her understanding of self continue in this allegorical text where the narrator charts out a map of herself through the places her mind and body occupy. Each story is thus named after the pausing points of this map –– On the Sidewalk, At The Trattoria, In The Bookstore, At My House, or simply, In My Head (of which there are three). In At My House, the narrator catches up with her old friend visiting town with her pompous husband and well-mannered child in tow. We don’t know what they look like but we know how the husband’s presence makes the narrator’s skin crawl. So much so that the feeling of distaste remains in her mouth long after their departure, much like the thin, almost invisible line made by a ballpoint pen on her couch by the friend’s child. She reveals the unhappiness that defined her childhood in In My Head, one that continues to plague her mind –– the discord between her and her mother, and her inability to explain the ‘small pleasures of solitude’ to her. However, In The Waiting Room acknowledges her fear of the future as she sees herself in another, where 20 years from then, ‘I wouldn’t have someone sitting beside me either’, she thinks.

Lahiri’s style remains simple and there is grace in her prose but oftentimes, it is that very elegance that takes away from the text that demands a slight reaction of passion. For being her first book in Italian, she hasn’t added any extra flair of cinematic or emotional nuance to her translation to a language she is more proficient with. In the story In The Bookstore, the narrator talks about her ex-boyfriend who had built a relationship very similar to theirs, with another woman at the same time. What could have been a more tumultuous a ride, leaves much to be craved. The two women’s confrontation many moons back comes to the narrator’s mind on encountering the ex at the bookstore. As the two women, exhausted from haunting revelations, decide to get a meal together, we realise we will never find out how the encounter in the present ended. The narrator has moved on to her solitude by then and we are left feeling slightly vacuous. Caught in the light and shade of the beach in In The Shade, she misses the ‘pleasant shade a companion might provide’. Her movements between appreciation and disregard for solitude births a slight ache in our hearts but we are compelled to soon forget it.

There are seasons, and places and time that mark her journey. We call it a journey because in her struggle for a place to belong, she has ended up packing her bags again and catching a train. “Because when all is said and don setting doesn’t matter: the space, the walls, the light” she writes in Nowhere. And yet it is those very things that make this thin collection of 157 pages a sublime and revelatory read.