Book: THE MONASTERY OF SOLITUDE: A JOURNEY IN SEARCH OF UNITY

Author: Moin Mir

Published by: Roli

Price: Rs 695

Salman Rushdie often writes about s**t. In Midnight’s Children’s final pages, he almost invites an open-air defecator into the novel. Rushdie’s book is an end-times parable about India (“sucked into the annihilating whirlpool of the multitudes”, reads its final line) and the narrator can’t help but find every little detail significant. Oneness and fatalism preside.

Moin Mir’s fascinating study, The Monastery of Solitude, is a work of non-fiction and bears no illusions about the times it stems from (around 2022; then it peeks across millennia), but some belaboured curatorial tendencies — the ones that exhaust Rushdie, tire out Lily Briscoe as she paints in Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse — seem to keep it from luminous greatness evident in each polished, pithy, reflection-encrusted sentence. Until the final pages’ truly masterly wallop that elicits the rare, world-affirming chuckle and nod from the reader, that appears to be a problem.

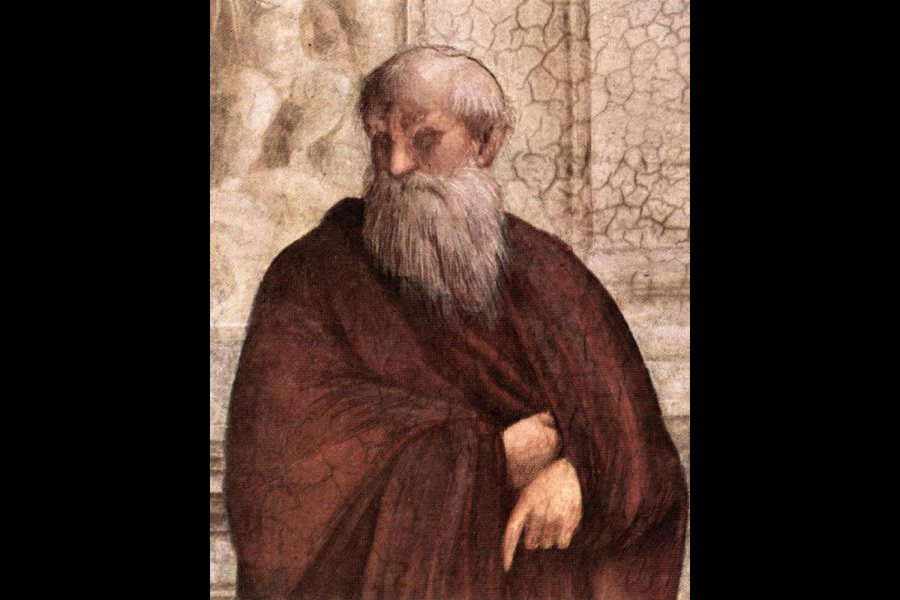

Mir’s ruminative despatches as he backpacks across Rome and Egypt are ornate and rife with ample humanity. His plan? Perfect for a hit BBC show: to retrace the steps of Plotinus, a philosopher from ancient Greece, who was enthralled by the Upanishads and wanted to travel to India to assimilate their lessons in their native glory. Plotinus, however, was thwarted by the course of history, a hunk of spittle in the face of what could have been an immense intellectual fortune. He meets Italian citizens and pals. He also meets people of Indian origin who have found a life in other places. The organising principle of The Monastery of

Solitude is unity. Mir quotes liberally from Plotinus’s Enneads. Caesar walks around. Images galore: the explosion of the original speck during the Big Bang jostles along with the undifferentiated, fine composition of delicious bread, the shimmering

coat of a river. Everything is intertwined, rooted in a singularity. For the longest time, there is no definitive statement besides this. One may accuse it of confusing forced individual perspectives with something grander, widespread. Travel writing is inherently experiential. Why does this one feel the need to make a priori claims towards universality?

A good example of this is him stumbling into the open door of a darkened monastery where he can see an old, supplicant woman crouched away from him. The coils of Mir’s coda ensnare her into his theory of everything. She’s praying: there are various modes of defining this besides Mir’s direction of a union of the self and the divine, per Plotinus, or the Advaita philosophy espoused by the Upanishads. But he chooses what he has to. Another example is him comparing the inner geography of a mud pot with a newly-discovered lumpy cosmic constitution. A beam of light illuminating the Pantheon is, per Mir, a sentinel of unity. It is easy to dismiss these many, many coy admissions of an abiding framework or semblance of theme (‘Lazy!’). But the author has other, higher motivations, and he achieves them with the momentum of a continent that is slowly, so slowly, entrenching itself into a consciousness. It is almost in the tradition of the pastoral novel: Mir never has any unsavoury episodes, and is a connoisseur of fine dining that always comprises some wine and some cheese and illustrious, folksy company. It is an idyll of cobbled streets and arched doorways and alabaster walls and fragrant orchards and generous farmers and wondrous art and plunges into cold waters while the sun throbs like a gong. It is filled with conversations that Mir, unlike Rushdie, is generous to integrate into the narrative.

Mir’s latest owes much to John Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley and Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost. Yet, in its structure, it is reminiscent of In Patagonia and The Songlines, both by Bruce Chatwin. Monastery is a meditative memoir from a writer who’s disappearing in the skin of his hero. By the end of the book, Mir approximates Plotinus, having learnt his lessons by walking in his footsteps. It is a probing, warm, even cheery account whose politics are humanist and uncomplicated, splayed across the anvil of deep, meaningful philosophy and threaded by a dogged pursuit of a singular (pun unintended) goal: an outlook that makes life whole again. The world is a chaotic, entropic mess. Any viewpoint that assembles it into a sensible composition is great and welcome. The book has good prose about war and living and morality and love and poverty and good manners. Mir thus provides his version of an answer and states, in the final line, that it has all the makings of a cult. He’s dead on.