Book: The Commissioner for Lost Causes

Author: Arun Shourie

Publisher: Viking

Price: Rs 999

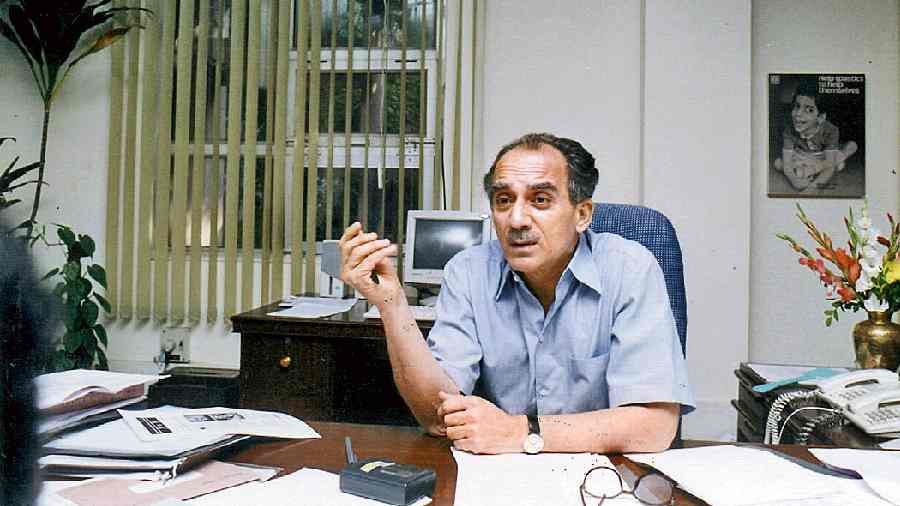

Arun Shourie’s memoir fills a gap in the prolific writing already available on some of India’s most turbulent years, when the Emergency, Bofors, Mandal Commission and Godman Chandraswami dominated political conversations in drawing rooms in South Delhi and South Mumbai, at tea shops across small towns, and on charpoys in rural India. These were years when corruption gnawed away at institutions and political morality had touched its nadir. Shourie is not merely a chronicler of those events. Unlike most authors who have written about that period, he was a participant, an instigator in prose of the equivalent of what are known today as ‘colour revolutions’, which have dethroned regimes in several countries. That is what makes Shourie’s latest book a compulsive read.

The book is 586 pages long, excluding acknowledgements and an index. If only Shourie had allowed his editors to do their job and cut down his text by half, this book would have had many more readers. Posterity would have benefited because Shourie’s experiences hold valuable lessons in nation-building in India where institutions are still fragile.

The best example of Shourie’s verbiage is a chapter on a strike in The Indian Express, where Shourie was editor. Many of today’s readers would think of this strike as nothing more than another industrial dispute notwithstanding Shourie’s efforts to portray it as a calamitous national conspiracy. Shourie devotes 29 long pages to this strike, even though the episode could have been entirely discarded without missing any message from the author.

It used to be said by Shourie’s colleagues in The Indian Express, the primary platform from where this indefatigable editor conducted many of his anti-establishment campaigns, that he starts work on a story by first giving its headline. Then he goes looking for facts to fit the headline and, somehow, motivates colleagues to join him in this search. This allegation is vindicated, unintentionally perhaps, in the chapter, “A conman takes us for a ride.” The lengths to which Shourie — along with the lawyer, Ram Jethmalani — went chasing known crooks, fixers and dubious dealmakers across continents even after it became clear that they had no facts at their command speaks poorly of his ethics in journalism. All of it was done in search of illusory facts to fit the newspaper’s headlines on the Bofors arms deal.

Shourie was immensely successful in many of his campaigns, which unseated chief ministers. He contributed substantially to the changing of at least three prime ministers. There is no doubt that his Magsaysay Award and Padma Bhushan are well-deserved. The flip side of his questionable practices is that a generation of Indian journalists, who followed Shourie, have adopted them and brought shame to journalism. Twisting facts to suit subjective goals gift-wrapped for readers as self-righteous truth-seeking has cost journalism credibility and lowered the ethical standards of the profession. Using sex workers to honeytrap sources and unacceptable impersonations disguised as sting operations are enlarged legacies of Shourie’s methods. When someone of his stature does the bidding of the notorious godman, Chandraswami — he justifies such actions in the book — can younger, aspiring editors and TV anchors be blamed for doing worse?

Once Shourie transformed from editor to politician, he tried to live by its ideals, often out of naivete in his new profession. His reservations — overruled by his poll managers — about the methods used in fighting elections and a loathing for the politics of convenience and preference for winnability — also preferred by his party — make for interesting reading.

Shourie’s last line promises another similar book, the next one dealing with his association with Atal Bihari Vajpayee and the author’s role as a minister in his cabinet. It promises to be a far more interesting volume because that book’s events are still relevant to the country. If only Shourie would practise brevity in his future writing.