Shortly after, on a trip to China for his company’s annual star awards on a rented private chartered plane, when Shanghvi was explaining to friend Sailesh Desai why he thought eggs are not non-vegetarian, his then India CEO Abhay Gandhi walked up to the magazine stands and started to flip through the pages. Desai called him from behind, asking, ‘Is there anything worth reading?’ Gandhi turned around holding up two magazines—Business Today and Outlook Business, both of which had the same face on their covers—Shanghvi’s.

This newly aroused curiosity about him spilled over to social media with questions on Quora like ‘Why is Dilip Shanghvi not much talked about as compared to Mukesh Ambani even though he’s the richest person in India?’ and ‘Why is India’s richest person (Dilip Shanghvi) so simple when compared to some of India’s richest men?’ His profiles on web multiplied by the day, and a Twitter handle that was not his surfaced and continued to tweet opinions on his name for well over two years.

A friend Piyush Doshi, who had once messaged him saying he was not happy to see him at No. 2 on India’s rich list, because he hoped to see him at No. 1, finally punched a congratulatory text. The boy Jai Shah who had seen him lift buckets of water from a common tube well for bath in the Paddapukur building in Calcutta, gasped with excitement as he compared the ‘extravagant opulence of Ambanis with the austere living of Dilip Uncle’. A wife of a friend who had not a long time back seen him fix the dent of their Maruti 800 turned emotional at the mention of his name.

‘No stars in his party, no guards by his side, no twenty-seven floors in the prime of Mumbai, no private jets parked on the roof, his is a lifestyle so simple that it can shame people with one-hundredth of his net worth,’ Jaya Butta, wife of friend Ashok Butta, says.

****

‘His is an unbelievable story I hope to tell my grandsons one day,’ said Milan Sinha, who had first seen Shanghvi waiting hours outside a doctor’s clinic in Bihar and then quietly walking off, because he had no money to pay for the taxi.

For many who have been part of his journey, Shanghvi’s spectacular rise to that height is the closest they could imagine to their own rise. They feel the pride of one amongst them having made it to the top. They feel they own a part of him, even though some of them struggle to remember the last time they had spoken with him.

And how did the man who did it take it? Reluctant, very reluctant to lose his anonymity and be recognized as India’s richest self-made billionaire. To those who called to congratulate, he used logic to cite how the indices had got their maths wrong.

He particularly misses experiences like sneaking into small south Indian tiffin shops like Ram Ashreya in Matunga on Sunday mornings to relish his idli-sambhar. A friend recalled someone walking up to him in the modest restaurant one day to tell him, ‘Hey, you look so much like Dilip Shanghvi! If I hadn’t spotted you in this crappy place, I would have surely mistaken you for him.’

Shanghvi has stopped going for his Sunday tiffins now, but his friends still pack his favourite south Indian dishes for him, and drop it at his place after their get-togethers. ‘I am not comfortable at all with this tag of “the richest Indian” and all the attention that follows for the reason,’ Shanghvi, for whom this label is more a distraction than a badge, said.

Benny Klener, his then global head of manufacturing, who had joined Sun from Teva, recalled an instance where Shanghvi offered him a lift. He stepped in to appreciate the fancy make of his customized limousine—a silver-grey Audi. But still new to Sun chief’s ways, he was surprised to hear his tone, almost apologetic, about using his luxury sedan.

‘For me a car is a car. It’s meant to serve the purpose of taking you from the source to the destination. But a few things in life you start doing because others strongly expect you to. To a business dinner party, you cannot wear slippers, even if at the end of a busy day they are the most comfortable wear. You have to wear formal shoes not to show up as an oddball and draw unnecessary stares. To me, this car is like those formal shoes, which you use not to be singled out for showing off your austerity.’ And then Shanghvi’s car moved on, because for him success has never been a destination.

Celebrated rich lists had already pronounced him the world’s wealthiest pharma entrepreneur, Asia’s only non-realty tycoon in the top ten wealthiest men, richest self-made Indian, but none of it had the earth-shattering effects to them, as the pronouncement made by Forbes and Bloomberg in March 2015.

Shanghvi with his net worth pegged at $21 billion had dethroned Mukesh Ambani to become the richest Indian. Albeit short-lived, not to last beyond months it was a moment of axial tilt for India in many ways — and not the least because the Ambanis, who had been a synonym of wealth and power in the collective memory of this country, had never been toppled from that much-envied seat since the wealth indices started applying to this part of the world.

It was in a sense the symbolic culmination of a process that began in 1991, when Finance Minister Manmohan Singh, while announcing ‘liberalization measures’ had predicted that they would unleash ‘animal spirits’ in businessmen. In a welcome change, India’s richest man hadn’t inherited his riches; hadn’t earned his fortune through cronyish connections or government concessions—common in sectors like energy, infrastructure or even telecom; hadn’t multiplied wealth by some gamble in finance or real estate. Shanghvi had earned his wealth not even by building a conglomerate, but by dint of focusing just on one sector—pharmaceuticals.

American academic Caroline Freund bracketed him in a select list of ‘Schumpeterian’ entrepreneurs, who were building and managing big companies that fought for their lives in the global markets, ‘a healthy consequence of structural transformation and rapid development’ of the (country’s) economy.

Manmohan Singh would cheer that description. Yet, you don’t have to be a businessman in India to know that cronyism is far from dead. But Shanghvi’s climb to the zenith of the wealth ladder stood for a hope, that meritocracy still has a chance. As the news spread like wildfire, Indians beyond the finance world, doctors, and the pharmaceuticals industry woke up to a surname—Shanghvi, and the man who so prized and preserved his oblivion became a subject of national curiosity.

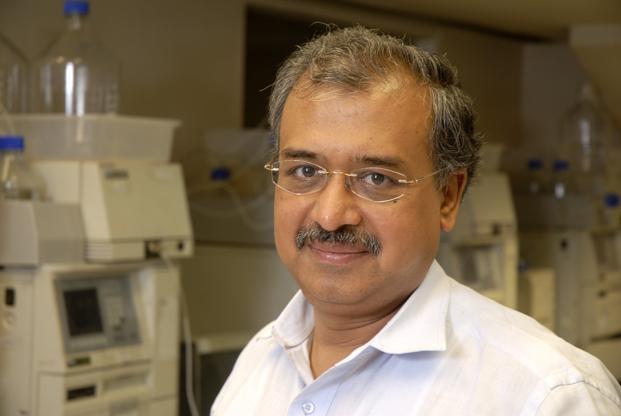

Pink papers realized that despite knowing him, they knew very little of his personal story to satisfy that curiosity. In that state of ill-preparedness, editors struggled to find a league to put Shanghvi in. Newsrooms debated whether he seemed closer to the league of Narayana Murthy and Azim Premji, but rejected it on the ground that he had shown far little commitment to philanthropy. They were in consensus that he surely didn’t belong to the league of the Ambanis or Adanis, and was far removed from the Tatas and Birlas. Without exception, all financial magazines and newspapers scrambled for an appointment with him and with or without managing one, put him on cover and page ones.

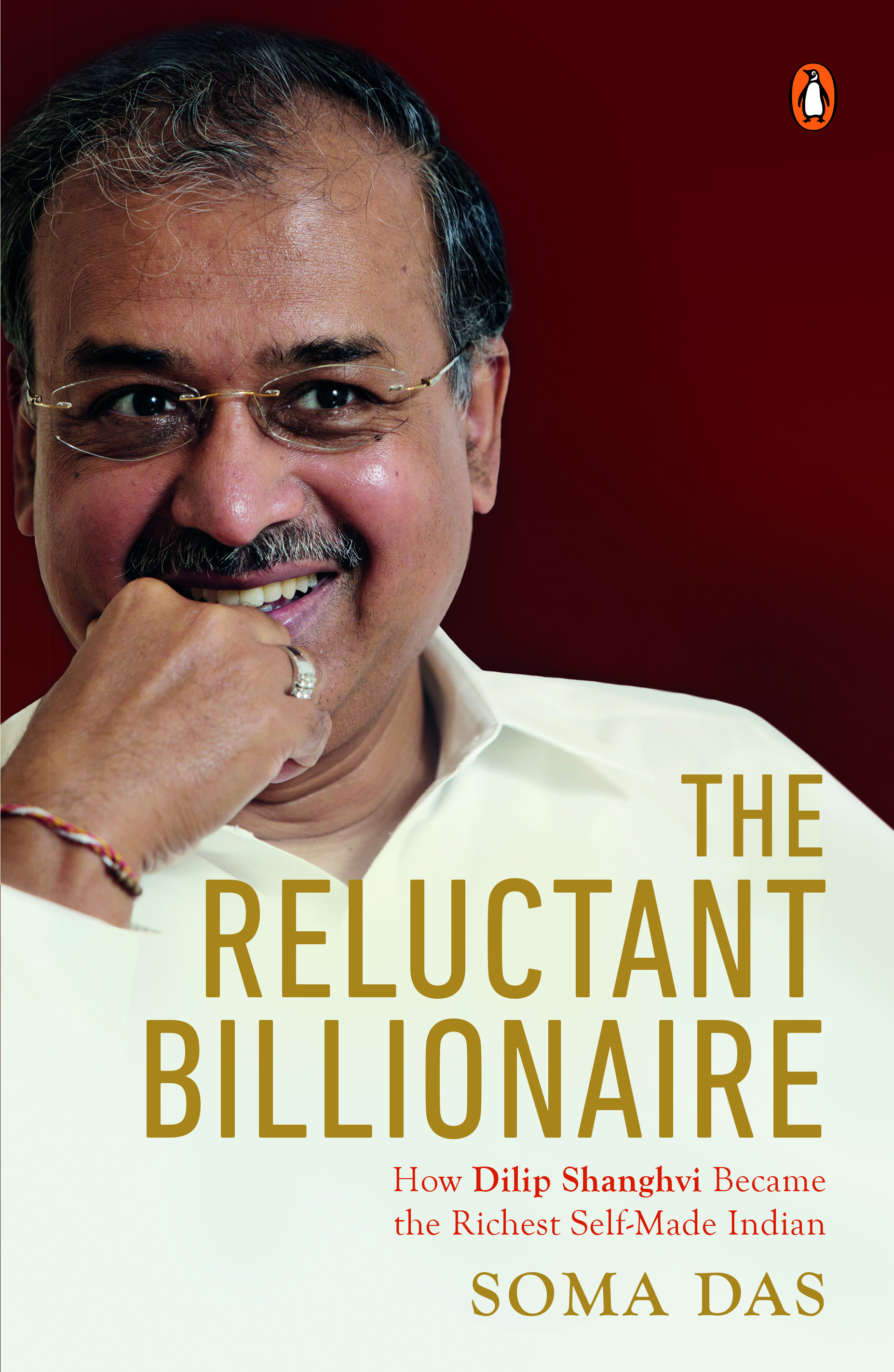

The Reluctant Billionaire: How Dilip Shanghvi Became the Richest Self-Made Indian by Soma Das. Excerpted with permission from Penguin Random House India

Book cover: The Reluctant Billionaire: How Dilip Shanghvi Became the Richest Self-Made Indian by Soma Das Penguin Random House India