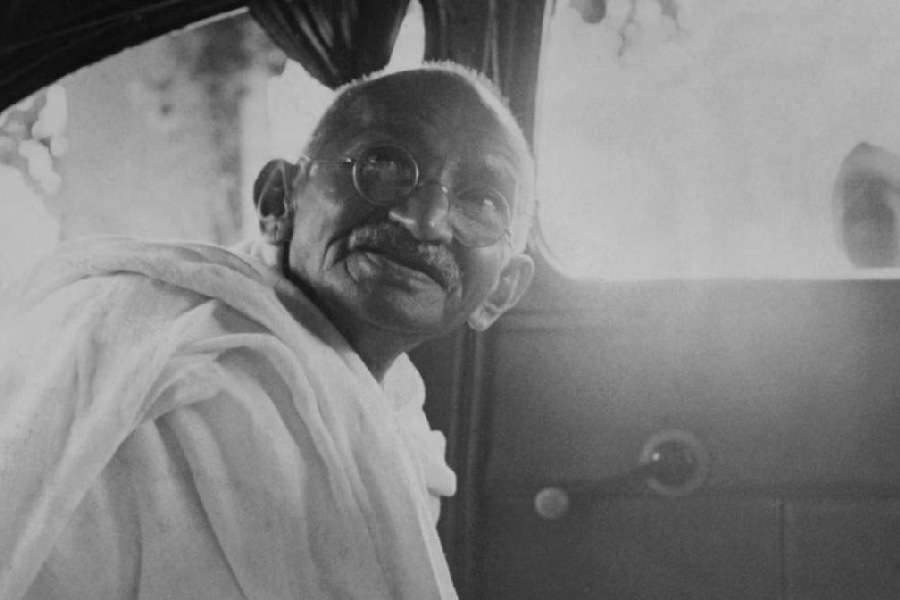

Book: BECOMING GANDHI: LIVING THE MAHATMA'S SIX MORAL TRUTHS IN IMMORAL TIMES

Author: Perry Garfinkel

Published by: Simon & Schuster

Price: Rs 599

Every year, numerous books on Gandhi of indifferent quality are added to our heaving shelves. One is sorry to report that, notwithstanding its ponderous title, Becoming Gandhi has little in it that can lay claim to a reader’s attention.

Having hit “rock bottom” in his personal life, Perry Garfinkel embarked on ‘Becoming Gandhi’. He sets out to achieve this by following — in a manner of speaking — what he calls Gandhi’s six moral truths or principles: truth, non-violence, simplicity, vegetarianism, faith and celibacy.

Since the volume betrays no awareness, one may recall here the origins of Gandhi’s principles. In 1915, when founding the settlement at Sabarmati, Gandhi had drawn up eleven ashram observances (ekadas vrat) that residents had to adhere to: truth, non-violence, celibacy, control of the palate, non-stealing, non-possession of property, physical labour, swadeshi, fearlessness, removal of untouchability, and tolerance.

Garfinkel’s six principles are loosely inspired by Gandhi and are based on an arbitrary selection and interpretation of the original ideas. In any event, merely following austerities, indifferently in this case, does not enable one to become a Gandhi. If that were so, India would be teeming with an insufferable number of great souls. It is the ends to which these principles are deployed — the pursuit of truth and justice — that made Mohandas Gandhi a mahatma. While Gandhi sought the moral elevation of people at large, the observances were primarily meant for inmates at his ashram. Most assuredly they were not designed as an aid to that tedious American genre of self-help hacks.

Throughout the volume, Garfinkel constantly conflates Gandhi’s principles with a jumble of examples drawn from an assortment of newspaper reports, academic studies and references to American popular culture. He thereby manages to reduce profound moral truths into idiosyncratic nostrums.

The volume is strewn with cringeworthy writing, including sentences such as “There will be a lot of inner work”; “Om sweet om, where it was”; and “I think of the brain as a circuit board of some sort, with wires attaching one part to another.” There are improbable parallels drawn between Gandhi’s views and Star Wars screenplays. Why, Garfinkel argues, Gandhi “might even have been cast as Yoda in the Bollywood adaptation.”

There is a word-by-word deconstruction of ‘Be the Change’, even when Garfinkel knows it was something Gandhi did not say. And, apparently, Rishi Sunak is “a testament to Gandhi’s own ‘Be the change’ mantra.” There are many other trite observations, including box insets on “How to Gandhi” at the end of chapters.

At one point in the narrative, the intrepid author tries to get a descendant of Gandhi to identify the spot inside Mani Bhavan “where he receives direct transmission and inspiration” from the Mahatma. Mercifully, the respondent did not allow the encounter to degenerate into a séance.

Garfinkel seems to believe that ignorance of one’s subject is a sine qua non for writing a book. He does not bother to acquaint himself with the elementary facts of Gandhi’s life. With a book deal in place and ready to go, the author did not know that Gujarat “was the state where Gandhi was born.” He fares no better at the end of the journey and believes that Gujarati is a “dialect” — of what language we are not told. Similarly, the unsuspecting reader is wrongly informed that the Mahatma lived at Mani Bhavan in Mumbai between 1917 and 1934 and was “a big fan of Shakespeare”.

Anything out of the author’s realm of limited awareness and experience is seen in poor, uncharitable light. The accommodation along the route to Dandi was “to be kind, rustic” and “didn’t have great bedding.” Garfinkel was further alarmed that the “meals were prepared in someone’s home kitchen and brought to the guests in a common dining room.” Worried about sanitation, he “could not envision Westerners feeling comfortable in this setting.” Incidentally, for all the hype, instead of walking the route, he ended up riding a car most of the way.

Taking his provincialism further afield, the author has an underwhelming experience in London. In 1931, during the Second Round Table conference, Gandhi stayed at Kingsley Hall located in one of the poorest quarters of that metropolis. The room in which Gandhi spent a few months is now maintained as a memorial. For this reviewer, it was a moving experience visiting the site but it left Garfinkel cold and unconvinced: “There was no desk or any other indication that Gandhi had stayed there. It was quite disappointing...”

Rambling, incoherent and replete with half-baked thoughts, Becoming Gandhi is a poor read. It is neither ersatz philosophy nor does it even provide the hackneyed comfort of the ‘Chicken Soup for X’ genre. Since he seeks to follow principles, it is a pity that the author did not recognise the virtue of restraint and not write this book at all.