Adil Jusswalla, who published Land’s End at 22 to critical acclaim while a student in England, has been in search of “home” for 60 years. His closest concept of home has been finding comfort with his fluidity in and familiarity with the English language. Excerpts from t2oS’ interview with the poet.

The first time I read your poetry was as a doctoral student at the University of Toronto. It was Diwali and I was missing home. I was reading Land’s End and it was a sledgehammer that hit me when I realised you had written this at 22, and you were out of the country and perhaps out of ‘home’. Could you recollect for us the spark that lit this first collection? Would you say you are still without the comfort of home, although you might be comfortable in the ‘space’ you live in?

The ‘spark’ as you call it for the poems in Land’s End was ignited by my sense of being an outsider in Britain, with no British past to look back to but with a language it gave me to use as I wished, to tackle, to master, to sing with... Hence no nostalgia, but a sense of loss — the loss of India, as the poet Zulifikar Ghose put it. I think that shows in my poems A Letter to Bombay and The Song.

Land’s End (1962), Missing Person (1976), Trying to Say Goodbye (2011) and Shorelines (2020) explore this idea of homelessness even though you might have many homes in the world. How would you define ‘home’ to the younger generation who are coming into an endangered world full of greed, ownership, and the lust for power?

I still don’t have a clear idea of ‘home’ or what its comforts mean, though I’m grateful to my parents and my brother Firdausi for helping me get the space I currently inhabit. Few in Mumbai have such a spacious view of sky and sea as I do. But I continue to live with the feeling that all of us, anyone, all over the world live in shelters, not homes that are permanent. And many live lives that have no shelter at all.

Your long-time friend, partner and wife Veronik seems to have been one of the centres of your world. Another was your brother Firdausi. How do you cope with the loss of a partner who was so exceptionally compassionate and creative like Veronik?

My latest work, a chapbook called Earth, deals a bit with the importance of Veronik in my life. But there’s a much bigger manuscript in the making which deals with much more of our lives and their losses. As for other members of the family, I find it increasingly important to resurrect their importance, once lost, to my life.

Your time at Cathedral School in Bombay, then St Xavier’s and Oxford, incidents that come to mind that you now think were very important in shaping your life and work…. Always wanted to ask you if studying architecture helped you in the structure of your poetry.

I had good teachers at Cathedral School, Mumbai, and much later, I enjoyed teaching at St Xavier’s College, Mumbai. I felt out of place at Oxford, more interested in whatever I found of nature in and around the city than my studies. I hope that comes through in my poems Drake and White Peacocks, two of my Oxford-based poems in Land’s End.

As a critic of your own work, how would you describe your trajectory through your many volumes of poetry?

I’m a poor judge of my own work and though it has got somewhere with awards, fellowship at the International Writing Program in Iowa City, some good reviews, etc., for which I am grateful, I don’t know who reads me or who finds it useful to read me with care. Of course there are responders like you who let me feel that I have been read with care, but they are exceptions. Should writers expect more, more than an attentive audience of one? I don’t know. Also, I see myself more as a poem-maker, a craftsman, rather than a poet. And what I take to be my muses — rarely mythological figures, mostly lighthouses, figures in paintings, stones of the earth that attract me — agree. They have yet to call me poet.

When asked in an interview by Peter Nazareth in 1978 about the peril of being incomprehensible, you had said: “Well, I think the situation of the poet in India is such that being misunderstood is part of his function.” Could you explain whether you consciously work towards a complexity which might make you sound incomprehensible as a poet, or is it just the Jussawalla way of using language and symbols?

No, I don’t consciously write to be incomprehensible. But my references and allusions are often literary and/or historical, and if readers don’t know where they come from, how could they ‘comprehend’ my work more fully than what their knowledge allows them to? Even in the supposedly post-Modernist world of Anglophone literature, isn’t this a Modernist situation, akin to what the Modernists went through much earlier?

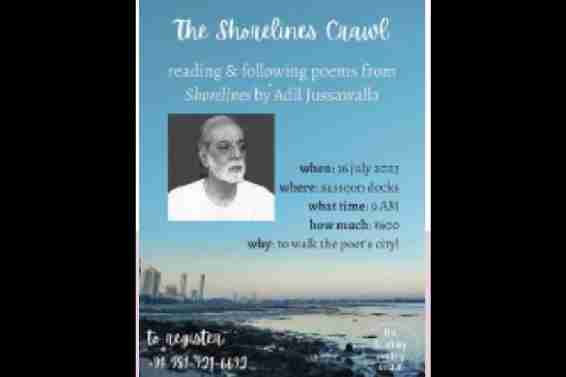

THROUGH ANOTHER LENS

The poster for The Shorelines Crawl

Explains the creative talent Saranya Subramanian, “I founded The Bombay Poetry Crawl in order to preserve, promote, and explore the works of 20th century Bombay poets. One of the walks under this series is The Shorelines Crawl, which is a walkthrough of Bombay’s dockyards, while reading Adil Jussawalla’s poetry. “Adil Jussawalla turns the city on its head, and makes us look at urban landscape through the lens of water, the sea, and the multiplicities of histories and mythologies that have shaped our lives on land. These poems carry multiple stories, temporalities and narratives of Bombay, which both take us out of the city, and urge us to look for things beyond the obvious. “The entire experience was deeply visceral, with the many smells, sights and sounds of Sassoon Docks heightening our crawl, and Jussawalla’s poetry asking us to find instances of humanity, gentleness and kindness in ravaged cities.”

Poet Adil Jussawalla wearing a scarf made by his late wife Veronik Picture: Firdaus Gandavia

In our landscape of poetry in India, what glimmers of light do you see for a new wave slowly coming in with some force?

Lots of glimmer, lots of light. But in anglophone poetry in India, in the absence of an anglophone literary culture, without a sustained and sustainable infrastructure that involves and connects schools, colleges, universities, publishers, libraries, etc., to hold it together, it may well be that the light and glimmer are no more lasting than those of glow worms and fireflies. That’s my fear.

Poet Dom Moraes adored your work. He wrote about Land’s End that it “seemed (to him and many other poets in England) one of the most brilliant books of poems since the War”. Do you recall that applause? Who were the poets who you go back to when you are in need of succour?

I gave Dom a copy of Land’s End in London and, as you point out, he was impressed. He even tried to find me a publisher for it in England, but wasn’t successful. Also, if the book was greeted with applause in Britain, I didn’t hear it. The poets I go back to are the ones who impressed me in my youth: Eliot, Yeats, Auden, Nissim Ezekiel, and later quite a few European and American poets.

With Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, Arun Kolatkar and Gieve Patel you set up the poets’ publishing cooperative Clearing House. Why?

Around 1975, the four of us had manuscripts but no publishers to send them to. So, we decided to publish ourselves and others in the same situation. We launched ourselves in 1976 and stopped publishing after 1984. Lobo by H.O. Nazareth was the last book we published. Our sales couldn’t match our costs.

The Adil Jussawalla papers, 1944-2019, at the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections at Cornell University has a fascinating collection of your correspondence with Dilip Chitre, P. Lal, Nissim Ezekiel, Salman Rushdie and other luminaries of the literary world. Why Cornell?

Cornell because of the interest and enthusiasm of its librarian Bronwen Bledsoe and the similar interest and enthusiasm of Anjali Nerlekar who teaches at Rutgers. Their commitment overrode any other consideration.