Book: The War Magician

Author: David Fisher

Publisher: Weidenfeld & Nicolson

Price: Rs 599

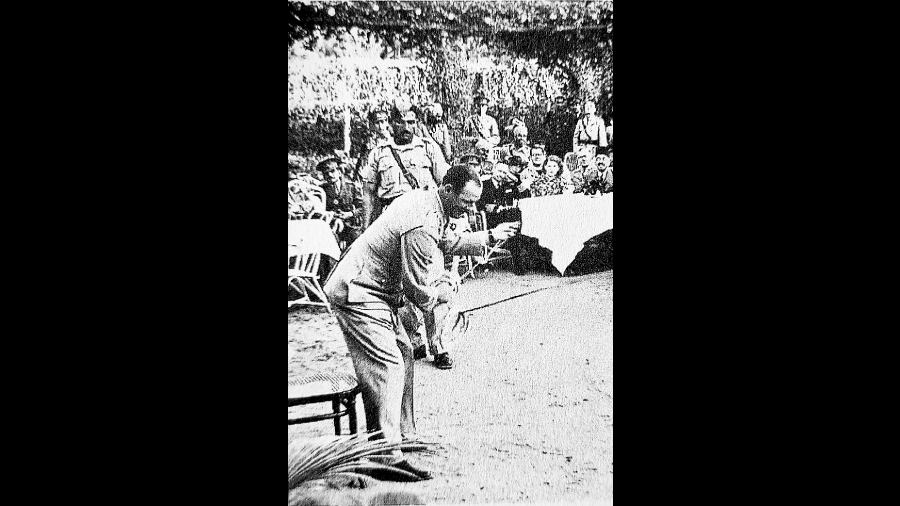

April, 1940. Adolf Hitler’s blitzkrieg was gobbling up Scandanavia at lightning speed. Meanwhile, the embers of the conflict had kindled a bonfire of British patriotism. There were long queues in front of enlistment offices all over England. One man, dressed in a suite, “a fresh flower [on] his lapel… joined the queue at the Reserve Officers’ Enlistment Centre at Hobart House.” The other volunteers chose conventional weaponry. But not Jasper Maskelyne (picture) — the man in the suit. He wanted to deploy magic to stop the rumbling Nazi war machine.

What unfolds thereafter is David Fisher’s faithful chronicling of the astounding feats of Maskelyne and his ‘Magic Gang’. The list of conjuring is impressive: Maskelyne made, among other things, the port at Alexandria disappear; the Suez canal went missing too — to evade the enemy; then there were the dummy tanks — yet another result of Maskelyne’s magic wand — that were in operation in North Africa against Rommel. Equally compelling are Fisher’s accounts of Maskelyne’s achievements for the MI9: he made tiny tools for escape and evasion that would have done Houdini proud.

Fisher does not let the reader remain perpetually seduced by Maskelyne’s tricks or his infinite moral energy — the drums of war echo constantly in the background. Neither does Fisher ignore Maskelyne’s inner struggles: the fact that he was a speck, albeit a luminous speck, in the gargantuan universe that was the Coalition army, “bruised his ego. After living in the centre spot for so long, he found it difficult to accept a place in the audience.”

The differences in attitudes between the adversaries towards illusion also make for a thoughtful exploration. Occultism was central to Nazi thought and imagination, while the Allies looked at magic as a utilitarian principle.

The War Magician is unevenly paced; so its spell weakens on occasions. But Fisher’s book does point to the need for World War II’s historiography to be more accommodating of those — men and magicians — who occupy its margins.