Conflict wreaks destruction; but it also engenders tales of resistance. Is the world ready to listen to them though? Narratives rooted in a specific language, context and culture inaccessible to a wider, international audience come with their own challenges. Take Syria, for instance. Even though this month marks 10 years of a civil war that refuses to end, very little of the Syrians’ day-to-day experience has made it out of the country’s borders. The linguistic barriers are a limitation. Translators are doing their bit to bridge the gap. As Alice Guthrie, a translator, puts it, the aim is “to keep translating as broad an array of Syrian voices as possible and getting people to read them”.

Interestingly, the graphic novel has opened up a new horizon to capture fragments of Syrian life. This is perhaps because image has an advantage over text. A translated text, no matter how true to the original story, always runs the risk of ‘cultural loss’ — some aspects, whether of setting or of plot, have to be left out owing to the stark differences between cultures. But art, powered by the universal seduction of the visual element, has helped the graphic novel transcend many of the constraints that more traditional forms of literature are confronted with.

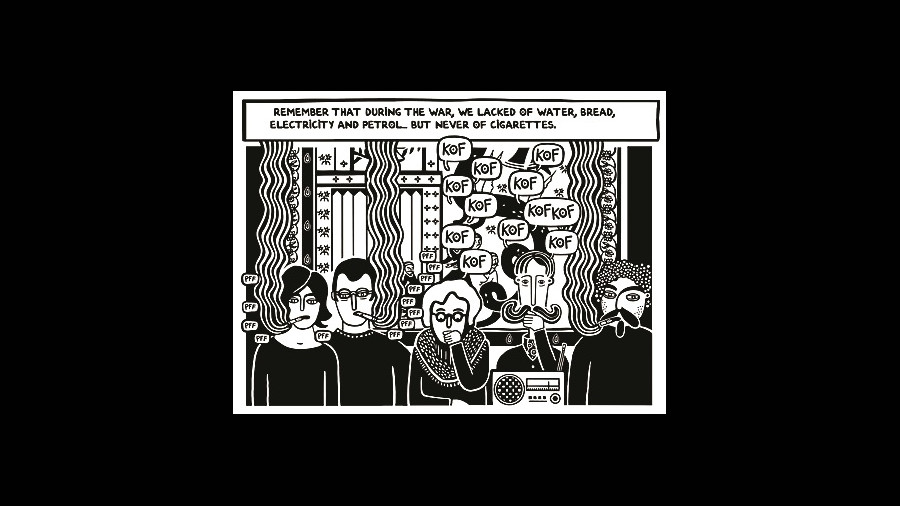

Consider Freedom Hospital by Hamid Sulaiman, a Syrian artist forced to flee his country, the dense, black-and-white panels of which convey the grimness of war-torn Syria sans verbal description. Zeina Abirached employs a similar colour scheme, although with a very different illustration technique, in I Remember Beirut (picture) to chronicle ordinary life in a war zone. The Egyptian artist, Migo, pits the striking orange of life vests against blue for much of the narrative in Eternal Refuge, switching to black-and-white to depict the past or instances of pain.

That the role of the graphic novel as a powerful narrative device has garnered widespread interest is evident not only from the rise in its popularity but also from the range of artists it is engaging. The South Korean artist, Kyungeun Park, has collaborated with a French journalist to tell the story of a young Syrian refugee, because Park “wanted to understand” the developments of the Syrian war.

The genre does more than evoke empathy. The graphic novel is a mirror for images that remain unseen. The illustrator, Molly Crabapple, points out that the authorities “[don’t] want people to see certain things and so there’s no photos that exist, but with art we can take people’s memories and we can make visuals from those.” Guy Delisle’s Pyongyang explores this scope for reportage that the medium offers by corroborating the high-handedness of the authoritarian regime.

The graphic novel is breaking boundaries: it found its way into the British Parliament in a debate on policy-making for refugees. Hopefully, the voices of resistance etched with image and text will only grow stronger.