Book: SHAKESPEARE'S SISTERS: FOUR WOMEN WHO WROTE THE RENAISSANCE

Author: Ramie Targoff

Published by: Riverrun

Price: Rs 899

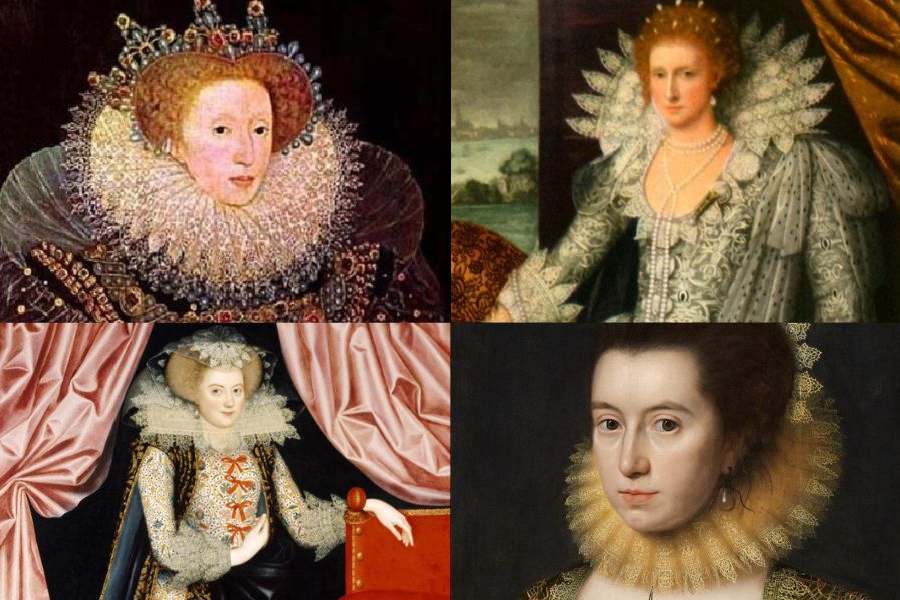

Meticulously researched and carefully written, Ramie Targoff’s Shakespeare’s Sisters illumines the lives of four extraordinary historical women — Mary Sidney (1561-1621), Aemilia Lanyer (1569-1645), Elizabeth Cary (1585-1639), and Anne Clifford (1590-1676) — who, because of their literary prowess, are claimed as Shakespeare’s sisters. Spread over fourteen chapters, the book demonstrates the creative and radical energies of these women expressed in poetry, dramas, memoirs, religious treatises, political histories, translations, diaries, petitions and so on. Targoff provides a wealth of information on the creation and the reception of these works. However, such writings, the book avers, were either meant for coterie consumption or for providing compensation for personal losses and failures or for petitioning authorities. The presence of female literature did not affirm women’s professional success. Whether Targoff’s title is valid or not thus deserves rethinking, especially since the book offers itself as a manifesto against Virginia Woolf’s pessimistic observations regarding Judith Shakespeare, Woolf’s imaginative sister of the great man.

Born into different degrees of privilege and pedigree in Renaissance England, the biographies of these four women underscore the complex courtly culture in which men, not women, prospered through their proximity to rulers based on birth, alliance or ambition. Women mattered in the marriage market on account of their social and material status, and not because of their educational abilities. Marriages were contracted; which is why the aristocratic but cash-strapped Mary Sidney was married off to a man thirty-eight years her senior, whilst Aemilia Lanyer, an outsider, could gain entry into court only after she became a mistress of a prominent lord. Her subsequent marriage to a nobody scripted her loss of status. Elizabeth Cary was born in a wealthy bourgeois family and it was her husband who gained from the marriage as he was “a cash-poor gentleman from a distinguished family.” Finally, while Anne Clifford did “become one of the greatest landowners in the kingdom,” her marriage to the profligate Richard Sackville, her first husband, produced, to quote her, “gay harbors of anguish.”

So, in what manner did these women ‘write’ the Renaissance? Importantly, while Mary Sidney was recognised as a coterie poet and as the sister of the famous Philip Sidney, neither she nor Cary published in their own names — Sidney used her titular claim and Cary used only her initials. For that matter, despite her vast treasure troves and textual archives, Clifford never published her writings. And while Lanyer’s first book of poems boldly proclaimed her name, her publication didn’t enhance her fame or glory. The ‘discovery’ of these writers is owed to subsequent history, to influential descendants like Vita Sackville-West, Virginia Woolf’s lover, who published Anne Clifford’s diaries, to scholars like A.L. Rowse who misrecognised Aemilia Lanyer as the famous ‘Dark Lady’ of Shakespeare’s sonnets, or to unknown Catholic writers of the 19th century who reclaimed Elizabeth Cary as a “heroic religious figure”. Notably, it is recent feminist historiography which has made available accounts of the women writers of early modern England. Targoff’s title and her project, then, should be regarded as contributing to the feminist debate over women’s possible renaissance and not as a definite treatise arising out of her observation that “Woolf’s doomed vision of women writers in Renaissance England was horribly mistaken.”

Given the paucity of information, Shakespeare’s Sisters interprets an array of sources for narrative purposes. But the question remains, what is new about these interpretations? Undoubtedly, though known, Targoff’s explorations of Cary’s rebellions against her husband and the King are rewarding as one learns of the severe hardships she suffered and the risks she took to stand by her Catholic faith. Equally, Targoff’s examination of the female Christian imagination in Cary’s representation of Mariam, the doomed wife of Herod the Great, or in Lanyer’s defence of the unnamed wife of Pontius Pilate, rightly draws on scholarship dealing with women writers’ feminised understanding of religion. However, in her discussion on Anne Clifford, Targoff chooses not to analyse Clifford’s politics, her Royalist beliefs, and feudal practices within a reasoned feminist perspective. Besides, the book’s relation between biography and literature is not always clear as Mary Sidney’s sojourns and possible liaison with her physician in later life do not proffer a new literary appraisal as there is no surviving record of her writings from that period. How women ‘wrote’ the Renaissance remains intriguing.

Almost fifty years ago, while reviewing the poetic canon, the critic, Harold Bloom, outlined his theory of anxiety of influence and argued that new and strong male poets ‘misread’ their powerful predecessors, their Freudian poetic fathers, to claim authorship of their creative endeavours. Why does Shakespeare’s Sisters replicate Bloomian patriarchal anxieties over Woolf’s views about Renaissance women writers? Why must contemporary feminism rehearse Bloom’s ‘map of misreading’ to prove Woolf wrong? Should we not look for more emancipatory and dialogic relations between the past and the present to connect literature, history and gender?