Lampooning Indira (Gandhi) for “living in a fool’s paradise”, 72-year-old Jayaprakash led a silent procession (through Patna) on April 8 (1974 to protest police excesses… Men and women, their lips taped and hands locked behind their backs, walked from the historic Congress Maidan to Fraser Road, Ashok Rajpath, Govind Mitra Road and Ram Krishna Avenue… Their placards had a uniform text: Hamla chahe jo bhi ho, hath hamara nahin uthega. (Whatever be the provocation, we shall not raise our hands in retaliation.) Prominent writers like Phanishwarnath Renu, Ramvachan Rai, Nagarjun (Vaidyanath Mishra), Ravindra Rajhans and Gopi Vallabh Sahay joined the procession and gave a new voice to the movement. When the procession crossed the city jail, hordes of detained students crammed the balconies, shouting slogans in support.

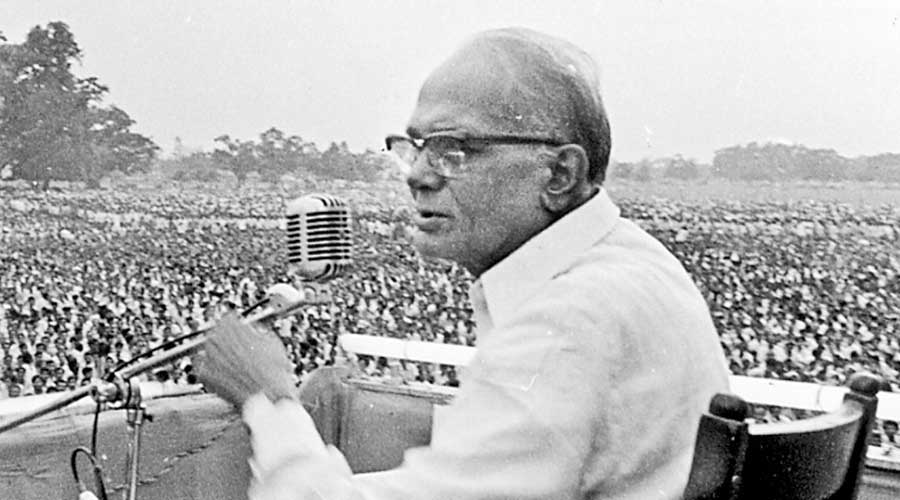

The next day, Jayaprakash addressed a large public meeting in (Patna’s) Gandhi Maidan. “For 27 years, I have watched events unfold, but I can stand on the sidelines no longer. I have vowed not to allow the state of things to continue.”

The sense that a revolution was brewing may have been naïve, but it was palpable. Twenty-six-year-old Lalu Yadav created a resonant moment when he proposed the title of “Loknayak” for Jayaprakash. The maidan reverberated with cries of “Loknayak Zindabad!” and “Inquilab Zindabad!”

A five-week long people’s struggle to bring down the government was launched on April 9. In Gaya, the struggle took an untoward turn on April 12 when the police opened fire on a restive mob. Eight persons lost their lives and several were seriously injured. There were reports of lathicharges on peaceful congregations of agitating students in many other districts. But, by then, the struggle had assumed the texture of a mass movement that was unstoppable. Women and young girls formed human barricades along the national highway. Several lawyers, teachers and other professionals joined relay fasts near the secretariat and other government buildings. Work remained paralysed in most offices.

All this while, Jayaprakash was struggling with medical problems. He finally had surgery for an enlarged prostate on April 23 at the Christian Medical College in Vellore. During his absence, hunger strikes and protest marches continued unabated under the leadership of Sarvodaya leaders like Acharya Ramamurti and Narayan Desai. On April 30, a marathon 12-hour fast was observed all over the state. On May Day, labour unions joined students in huge processions...

On June 5, the procession headed by Jayaprakash began its march from the Gandhi Maidan at 3pm. Behind his open jeep was a truck carrying bundles of papers with five million signatures collected from different districts, in favour of dissolving the assembly. The procession reached the governor’s house at 5pm. Jayaprakash handed over the papers to the governor before a brief detour to the Gandhi National Museum for a little rest. As soon as he was ready to move, protestors began marching back to the Gandhi Maidan. While crossing one of the main streets, they were attacked by the “Indira Brigade”, a rogue group nurtured by a Congress MLA. The government spared no effort in scuttling the event. Several train, bus and steamer services were disrupted. Despite the impediments and the soaring June temperature, a million people gathered at the venue to listen to Jayaprakash. They were not disappointed. His speech, delivered in impeccable Hindi and strong on emotionally engaging rhetoric, was evocative of the heady revolutionary days of 1942. As Hannah Arendt wrote, “Even in the darkest times, we have the right to expect some illumination.”...

Jayaprakash spoke like a true revolutionary, sure of himself and his instruments. “Friends, this is a revolution, a total revolution. This is not a movement merely for the dissolution of the assembly. We have to go far, very far… Nobody, Jayaprakash Narayan or anyone else, can stop this movement. It was born because this system of education is rotten and the students don’t see a ray of hope. It was born because the people are being crushed under high prices. There is corruption and bribery everywhere. Unemployment goes on rising, both of the educated and the others. Otherwise a thousand Jayaprakash Narayans and a thousand Chhatra Sangharsh Samitis could not have created a mass movement like this.” At the end of that exceptionally charged day, closeted away from the crowd, in a tired and barely audible voice, Jayaprakash said, “Revolution has come, but now when I have grown old.”

Jayaprakash’s speech had a visceral impact on Indira. Their relationship was going through one of its lowest ebbs, caught in a spiral of outrage, distrust and recrimination. It started with Indira’s address at a public meeting in Bhubaneswar on April 1, where she accused her detractors of living on the largesse of corrupt people. Her provocative remark, clearly alluding to Jayaprakash, was not a silly gaffe that could be ignored. In a statement issued two days later, Jayaprakash accused her of descending to the lowest depths. Realising that she had made a mistake, Indira tried to make amends. She wrote, “Many friends are distressed that there should be any misunderstanding between us. I have had the privilege of your friendship for many years. The mutual regard that existed between my father and you is well known as is my mother’s affection for Prabhavatiji. Even the highest personal regard and affection need not preclude an honest difference in political or philosophical outlook. You have not seen eye to eye with my father, nor now with me. We have criticised each other, but I hope we have done it without personal bitterness or questioning of each other’s motives. I have consistently tried not to be confined by my office, but to reach out for ideas, for understanding and for cooperation in the task of solving problems. I shall continue to value your sympathy.”

Indira’s attempt to bridge the chasm did not succeed. Jayaprakash’s letters to her took on a brusque, hostile tone. The form of address also changed from Indu to a formal Indiraji. His public address of June 5 further distanced them. In response, Indira wrote, “You are angry that people from the prime minister and Shri (Umashankar) Dikshit downwards ‘have the arrogance to give lessons in democracy to Jayaprakash Narayan’. Would you not agree that democracy gives us the right to think and talk about it, as it does to anybody else, irrespective of position or background? May I also, in all humility, put to you that it is possible that others, who may not be your followers, are equally concerned about the country, about the people’s welfare, and about the need to cleanse public life of weakness and corruption. Are you sure that all the people who today follow you and support your movement are different in their background and intentions from the people, who, according to you, have found shelter behind government?” Jayaprakash chose to ignore the letter.

Reproduced with permission from The Dream of Revolution: A Biography of Jayaprakash Narayan by Dr Bimal Prasad and Sujata Prasad; Published by Penguin Random House