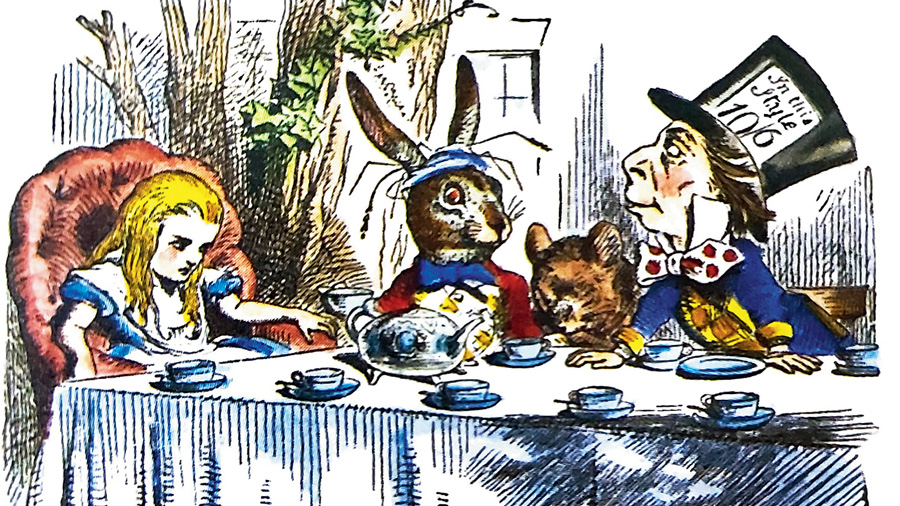

“Why is a raven like a writing desk?” Is this query plain cuckoo or merely proof of an eccentric mind? The answer has divided readers into opposing camps for decades. But is there really a difference between the Mad Hatter, who had come up with this seemingly nonsensical riddle, and say, Bertie Wooster, when he asks, whimsically, “Do trousers matter?” What better time than the Mad Hatter Day — celebrated across the United States of America in early October — to probe the consequences of the blurring of the line between mental illness and oddity when it comes to literary characters?

The problem with trivializing Mad Hatter and considering his inquisitiveness to be ‘eccentric’ is to suggest that he had a choice to act the way he did. “Unconventional and slightly strange” behaviour — the trademark definition of eccentricity — has been listed as an early symptom of diverse mental ailments. But if we were to look at the Mad Hatter’s ‘ailment’ under the lens of modern-day psychoanalysis, it would appear that he was, medically speaking, ill. Calling him eccentric, thus, diminishes the gravity of the problem. The Hatter has not been the only literary character to grab the attention of mental health professionals. The White Rabbit’s obsession with promptness and, consequently, his paranoia with time has been linked to general anxiety disorder. Alice herself is said to exhibit symptoms of paranoid schizophrenia.

When reading Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the reader must reflect on Lewis Carroll’s intention behind the portrayal of characters like the Mad Hatter or the Rabbit. By introducing this playful idea of madness, Carroll chose a striking point of entry into a frenzied discourse at a time when people with mental illness were suddenly becoming visible to not only the public eye but also coming under the glare of the State. The Victorian age coincided with the profusion of mental institutions — lunatic asylums started to gain ground around this time — diagnosis, and legal categorization of lunacy. The madness of Wonderland was an act of resistance; the strain defied many Victorian ideas concerning madness; lunacy, apart from being all-encompassing, seemed to be lit with the light of liberation. The following dialogue between the Mad Hatter and Alice challenges — indeed subverts — some of the fundamental tenets of madness: “Mad Hatter: ‘Have I gone mad?’ Alice: ‘I’m afraid so. You’re entirely bonkers. But I’ll tell you a secret. All the best people are.’”

Have the times changed though? Although Carroll’s creations exhibit decidedly neurological anomalies, even young readers no longer consider them to be deranged. They are mostly looked upon as a group of perplexing, lovable, oddballs.

Now does that mean that 21st-century children too have lost their marbles?