Book: A country called childhood: A Memoir

Author: Deepti Naval

Publisher: Aleph

Price: Rs. 999

“My childhood was full of stories,” writes Deepti Naval in her latest book, A Country Called Childhood.

Stories of her as a ‘little’ girl growing up in Amritsar in the 1950s and 1960s, stories of her mother, Himadri, who was born in Burma and spent much of her early years there before moving to Lahore where she developed her passion for art at the legendary Sanyal Studio, stories of her father, Uday Chandra, who acquired a Master’s degree in English Literature from the famed Government College in Lahore, stories of her elder sister, Smiti — the siblings were, in Punjabi-style, known as Bobby-Dolly — stories of her friends, cousins, teachers. Stories that shaped her future. Stories that are as much hers as they are of a nascent nation that was trying to find its feet after the trauma of Partition. Hopes were high, aspirations boundless, means limited, at least for many.

Naval’s memories are of a child who was oblivious to the imaginary boundaries of religion or nationality as she writes with warmth about her family home, Chandraavali, in Amritsar, which was within touching distance of the Khairuddin Masjid, a mosque built in 1876. She recounts — as told to her by her father — the role of the mosque as a symbol of harmony. On April 9, 1919, she writes, a jaloos (protest parade) was taken out in Amritsar’s Hall Bazaar at which the British fired and around 20 people were killed. The victims were all brought to the mosque to be bathed in the pond, irrespective of their faith — Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus. Their funeral processions started from the mosque, together, and on April 13, to protest against the killings, a gathering was organised at Jallianwala Bagh. The horror that followed changed the course of Indian history. By a quirk of fate, Deepti’s first film role in Bombay would be in a 1977 movie called Jallian Wala Bagh.

But this is not a book about films, although Naval weaves movies into the narrative, a hint of the vocation she would take up later in life. Like the time she missed seeing Tumsa Nahin Dekha, or how she loved Raj Kapoor’s Jis Desh Mein Ganga Behti Hai, Sangam and Mera Naam Joker. Or the posters she collected of Meena Kumari. And her ‘craze’ for Sadhana.

Naval’s book is a love tribute to her parents — Mama and Piti as she called them. Mama painted, Piti loved the arts and literature — it was Uday Chandra who decided to do away with the family surname, Sharma, as he wanted something new, so Naval (new) they became. For Deepti, a sensitive child and teenager, her parents were her world.

The book is also about Amritsar, or Ambershire as she calls it. Naval takes us through the streets and lanes of Amritsar, painting a vivid picture of life during the early, tumultuous years of Independence.

Just into her teens, the realities of war hit home. She was naïve; her innocence, she recalls, made her excited about what was going on along the border not too far from her home.

“We jumped up with excitement! A real war? At the Amritsar border?” she writes, recalling how thrilled she was when news crackled on All India Radio that Pakistan had attacked India in 1965. “Finally, something was happening in our lives! Something important! We were going to become part of history!”

But her father wanted his children to understand the realities of war, even if Naval was just 13 at the time. He drove them to Khem Karan, where, Naval writes, she saw the shattered tanks, smelt the scorched earth and saw the multitude of bodies lying all around.

Naval’s memoirs are candid. She speaks of the troubles her parents’ relationship went through, the bitter fights they had. It was a long marriage, but her parents split when they were in their seventies and after the family had moved to the US where her father had taken up a job.

Naval also speaks of her inner demons — she once ran away from home so she could be in Kashmir, which, from the impressions she had developed seeing the movies, was paradise.

Her first kiss (with a friend) was not something she enjoyed, Naval says she turned as white as a sheet. Naval also talks poignantly about her friend, Neeta Devichand, who was admitted into a mental asylum in Punjab after she tried to take her life.

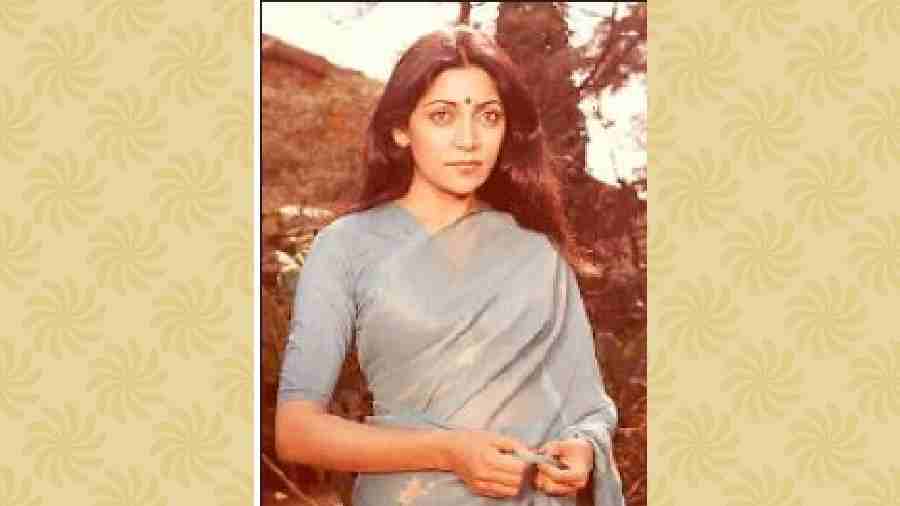

Naval has worn many hats in her distinguished career. An actress who held her own against the likes of Shabana Azmi and Smita Patil, a painter, writer and photographer. Her memoirs offer a glimpse of life in those heady days in the aftermath of Independence, seen through a very different prism. But she stops in 1971, when she was about to step into adulthood. Given her research, eye for detail and lucid prose, one can only hope that Naval will offer a peek into her life and career after that as well. Maybe a living document of Bollywood and beyond, warts and all.