THE FINAL FAREWELL: UNDERSTANDING THE LAST RITES AND RITUALS OF INDAN’S MAJOR FAITHS

By Minakshi Dewan

Harper Collins, Rs 499

Death completes life. Almost every faith believes death is predestined. But unprecedented deaths are far too common, inviting a unique grieving process. There’s something standardised in almost every religion — the end-of-life rituals. These are heavily gendered, too. While documenting the same with empathy and sensitivity, Minakshi Dewan argues that such rituals have the potential to provide a way of grieving and healing.

The Final Farewell, however, unpacks much more. In the first few chapters, Dewan covers funeral-related traditions and practices observed among Hindus, Sikhs, Muslims, Christians, and Parsis. Each faith has its own understanding of life after death as well as ritualists and specialists who oversee burials and cremations and strictly outline the dos and don’ts. For example, an “excessive display of grief” is discouraged in the Sikh tradition while professional mourners — rudaalis — are called upon as a norm in many other communities. Furthermore, Dewan does a great job at highlighting vocabularies related to death in each religion as well as contextualising the changes society has witnessed when it comes to bidding the final goodbye. More women, she notes, are seeing their loved ones off till the crematorium and performing rituals usually slated for men. She also notes the growing acceptance of environment-friendly options for burial. But even death is not spared the chasms that blight the world of the living. The space for the burial of Muslims continues to shrink. Dewan writes that the number of Muslim graveyards in Delhi has reduced from 500 in 1970 to less than 100 now. In several parts of the country, Dalit communities are forbidden from burying their dead, forcing them “to cremate or bury their loved ones next to their living quarters.” Dignity in death is, evidently, a selective right.

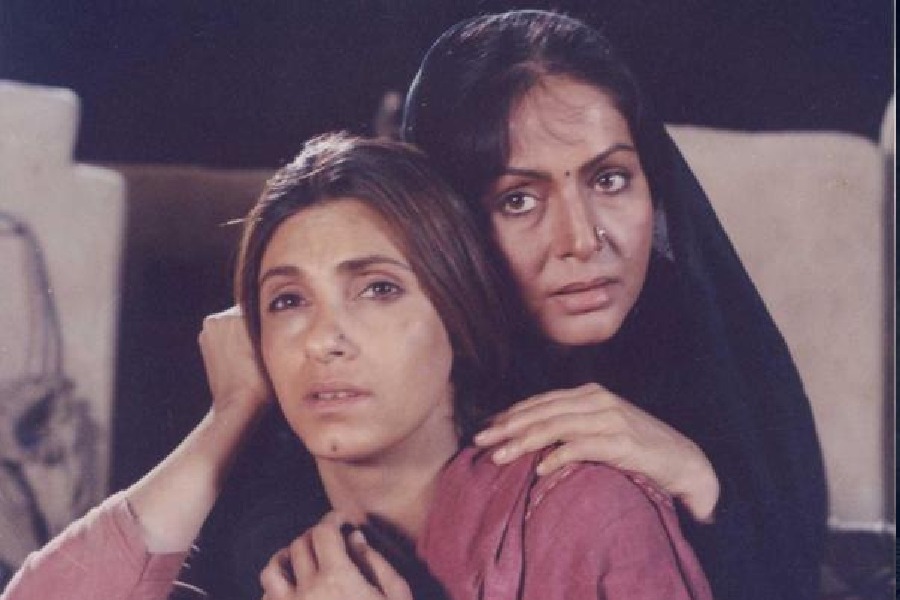

To Dewan’s credit, the book accords substantial attention to the intersections of caste and gender. Covering a range of actors, from ritual technicians and cremation workers to professional death-care service providers and support groups for dealing with loss, she manages to document insightful and courageous stories, including how cinema portrays bereavement and is helping challenge the norms. Besides death-related geographies and histories, Dewan dexterously documents the economic aspects as well. From low-income families being burdened with the performance of grief and offering a feast after the funeral to noting how India’s death-care service industry is burgeoning at $2.5 billion, she demonstrates an eye for a three-sixty-degree scrutiny of the subject at hand. Had it not been the case, the trans people’s defiance of the rigours of caste, gender, and religion even in death, or the fading tradition of funeral performances and the growing interest in these as an art form, would have remained undocumented. Without discounting the brilliantly researched insights, the book could’ve benefited by ridding itself of redundant and oft-repeated sentences. The resultant brevity would have infused new life into this book on death.