Book: NOTES ON AN EXECUTION: A NOVEL

Author: Danya Kukafka

Publication: Orion

Price: ₹699

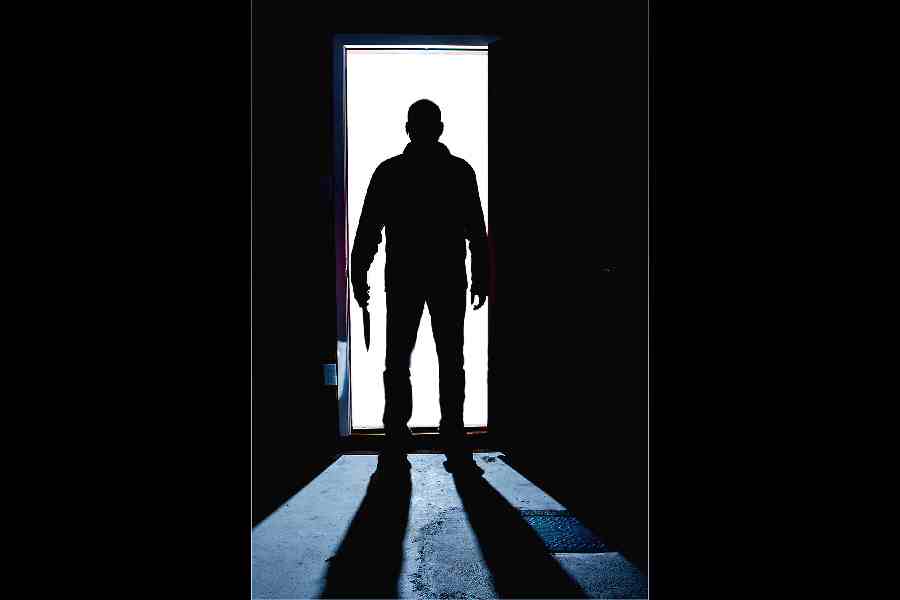

When we meet “The Girly Killer”, Ansel Packer, he is on death row and is 12 hours away from execution. There is a grinning, psychopathic elephant in the room — on the ceiling to be specific — formed with a pattern of water stains, who seems to know what he is thinking. His favourite hidden place in his cell has an atypical graffiti scrawled on it by one of the cell’s previous occupants. “We Are All Rabid,” it says.

But Ansel does not seem rabid, even though he thinks it is contextually “hilarious” and true. He seems almost fully functional and stable. Mixing paint, painting a picture, cooking a scheme, and writing his “Theory”, which he maintains is not a manifesto since manifestos are “for crazy people” and he is not one. “Manifestos are incoherent, scrawled hastily before pointless acts of terror.” No, his theory is more of an exploration of “the most inherent human truth. No one is all bad. No one is all good. We live as equals in the murky grey between.” This ‘inherent truth’ is what Danya Kukafka explores in the story, which is more of a ‘whydunnit’ than a whodunit. In this fashion, it reminds one of Keigo Higashino-style books where the questions of how the murders are solved keep the readers hooked.

But more than the suspense, it’s the steady tick of the clock that adds to the tension. As Ansel’s stopwatch winds down, we come to know how his “actions would become a chain marching purposefully into the present.” Part of those links that form this ‘chain’ are the women who continue the narrative through another timeline — Ansel’s mother, Lavender, the detective, Saffron Singh, or Saffy who was hurt by him in childhood, and Hazel Fisk, Ansel’s wife’s twin sister.

Kukafka has given Ansel a background that reads like a textbook psychological profile of every fictitious or real-life serial killer — early history of abuse and abandonment, childhood instances of killing animals, a strange kind of animal magnetism over women and even instances of impotency. And, yet, he is also deliberately cast as an awkward, ridiculous figure. He is handsome but “with oversized glasses” and pants that “were slightly too short at the ankle, a few wiry leg hairs curled beneath the cuffs.” His “Theory”, which he believes will redeem him from his crimes, has little academic or philosophical merit.

Instead of the larger-than-life image afforded to serial killers in pop culture, those three women whose lives are affected by Ansel, who overcome loss, horrific abuse, and trauma, make Notes on an Execution a compelling read. Lavender’s escape from abuse is never used as a way of transferring the sins of the son to the mistakes of the mother. Saffron’s rise to a detective despite her race and gender and her sheer doggedness bordering on obsession when it comes to catching the killer and even Hazel’s recovery from a debilitating loss make the women the heroes.

“I am awake in the place where women die.” This quote by the artist, Jenny Holzer, is in the beginning of the book. Just like her, these three waking, thriving women subvert the common narrative where the serial killer becomes the fancy of zeitgeist.