When Somerset Maugham’s The Moon and Sixpence appeared in April, 1919, there was no question of a Moon Day in July, commemorating humankind’s first steps on the moon. The earth’s friendly satellite was then still too deeply a part of people’s dreams and aspirations, too often a part of their wit and folklore to be thought of as a surface to walk on. The Old Woman in the Moon and the Cow that jumped over it were as much a part of moon culture as its presence as a symbol of romantic love and impossible dreams.

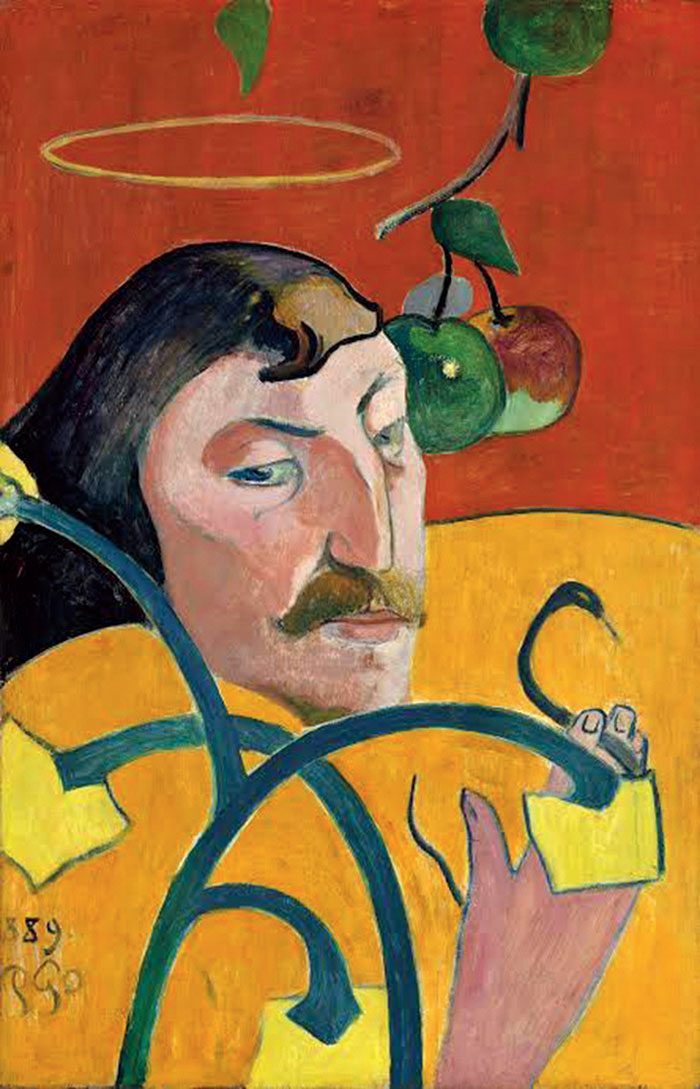

It is characteristic of Maugham’s dry self-deprecation that he should choose a critic’s phrase about his previous novel to name his new one. The main character in Maugham’s Of Human Bondage is supposed to be “so busy yearning for the moon that he never saw the sixpence at his feet”. The author found in this the perfect title for a novel based loosely on the life of Paul Gauguin. Gauguin’s restless search for untried methods of creative expression, his rebellion against accepted norms of ‘seeing’, his impatient refashioning of his own art must have made him, for Maugham, a man with unblinking eyes on the moon, forever spurning the sixpence at his feet.

Charles Strickland in The Moon and Sixpence abandons his family and a stockbroking job to satisfy, untrained, his urge to paint. Indifferent to his own physical needs and brutally selfish towards others, he works at his art — which no one buys — in Paris, Marseille and finally in Tahiti. Strickland’s life and character seem far more dramatic than Gauguin’s, for Maugham strips him of the companionship of peers Gauguin had in the early years, and anything equivalent to the intimate and turbulent relationship he had with Vincent van Gogh. But Strickland does take on the contours of the tortured, undervalued, path-breaking genius that is Gauguin’s enduring image too.

Maugham manages Strickland’s transformation from colourless family man to ‘possessed’ artist by conveying the slightly distanced amazement of the first-person narrator, a writer driven by an irrepressible curiosity about human nature. As Maugham was. The heartless genius is contrasted with the golden-hearted mediocre artist, Dirk — a theme perhaps prompted by Maugham’s complicated response to criticism of his own work. For The Moon and Sixpence, however, the assessment should turn on Maugham’s daring attempt to put an Englishman in the place of a controversial European artist, whose life, including his bringing up in Peru, must have been strikingly different, even in terms of the perception of colours and shapes, than can be imagined in a conventional English childhood.

Yet in Strickland Maugham suggests also the shadows of the dark side of the moon, towards which Chandrayaan 2 is now headed.