Does solace have a place where war is the norm? Are victims of violence allowed to rehabilitate and reintegrate? What is the price one must pay for peace?

The conditions of war zones and post-conflict societies may have their insidious inflections, but they are united by a central paradox — the daily negotiation between hope and fear.

Meha Dixit’s book, Piece of War, explores this negotiation in great detail, documenting the author’s experiences while travelling through turbulent societies around the globe. Having completed her PhD in international politics from Jawaharlal Nehru University, Dixit has been a professor at Kashmir University, besides working with several international organisations, including Amnesty International and Save the Children.

Filmmaker Sangeeta Datta welcomes Dixit and Dutta Telegraph picture

As guest speaker on An Author’s Afternoon, organised by Prabha Khaitan Foundation in association with Shree Cement Ltd and Taj Bengal, Dixit discussed some of her insights from the writing of her latest book, in conversation with Esha Dutta.

“Everyone has their own prisons, but in militarised societies, these prisons get aggravated,” said Dixit, pointing out that those she met during her travels — from Afghanistan to Ethiopia, from Kashmir to Lebanon — were essentially ordinary people living through extraordinary crises.

“They also listen to music, play instruments or sports, spend time with their families, or socialise, whenever they get the chance,” Dixit said, elucidating that in the process of sympathising with people living in conflict-ridden societies, we must not end up exoticising them.

Meha Dixit (right) in conversation with Esha Dutta Telegraph picture

Shifting her focus to children and women, Dixit analysed how sexual abuse is not just a byproduct but a strategy of war. The use of sex slaves is a common phenomenon, she explained, as a means for sustained subjugation.

While each place had its own pain and suffering involved, Dixit admitted finding it most difficult to navigate through Afghanistan.

“I was on my way to Jalalabad (in eastern Afghanistan), when both the Taliban and ISIS had their presence there. I had to travel in a shared vehicle, cover myself entirely, and remain absolutely mute during the four-and-a-half hour journey,” recounted Dixit, adding that she could not disclose her Indian identity for fear of being suspected as a spy.

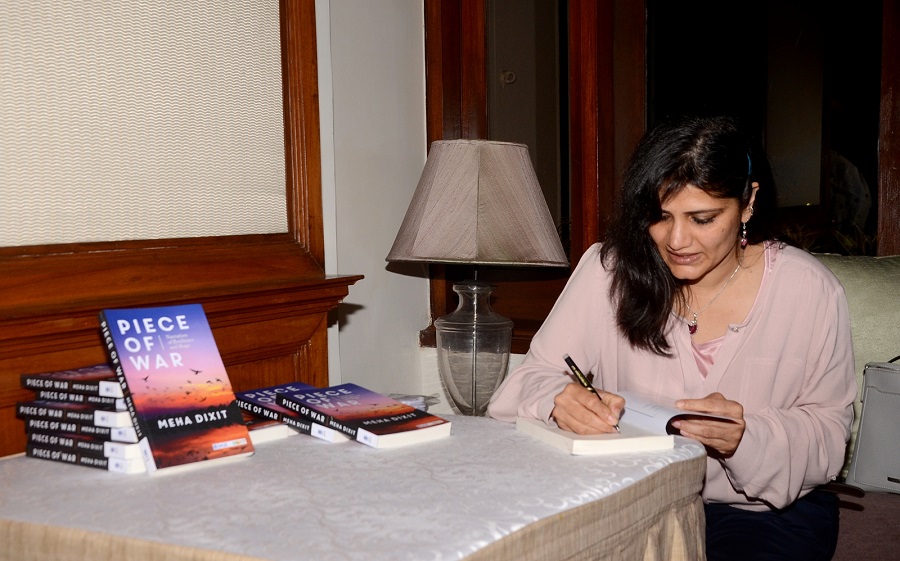

Meha Dixit signs copies of her book for the audience Telegraph picture

Dixit shared with the audience — a handful of them attended in person at Taj Bengal while a larger number tuned in remotely — how the people she has kept in touch with over the years from conflict zones have often come across to her as fatalistic: “Living under such challenging circumstances can lead one to accept that this is how things are meant to be. But that’s not to say that these people lack hope. Sometimes, they can be quite optimistic, radiating hope, and at others, they appear broken… as a result of all the psychological fatigue.”

Dixit proceeded to address questions from the audience, unraveling how romanticisation of war among the youth operates through gender roles, besides the contribution of repeated injustice in seeding terrorism: “Often, young people take up arms simply because they are not being heard.”

On a concluding note, Dixit commented on her own sense of belonging after her prolonged travels: “I really don’t have a specific sense of belonging now… I feel like I belong to everywhere I go, because, thankfully, I am able to adapt very easily to different situations.”