A big fan of ancient history, Devi Yesodharan believes storytelling to be a bridge. Just like her protagonists Nita and Rouhi, who hold on to that bridge, in her latest book, The Outsiders, the readers also connect with the migrant factor that she brings with her new narrative. Yesodharan, who was longlisted for the JCB Prize for Literature and the Tata Lit Live! First Book Award, talks about revisiting Dubai with the book, blurring boundaries and more.

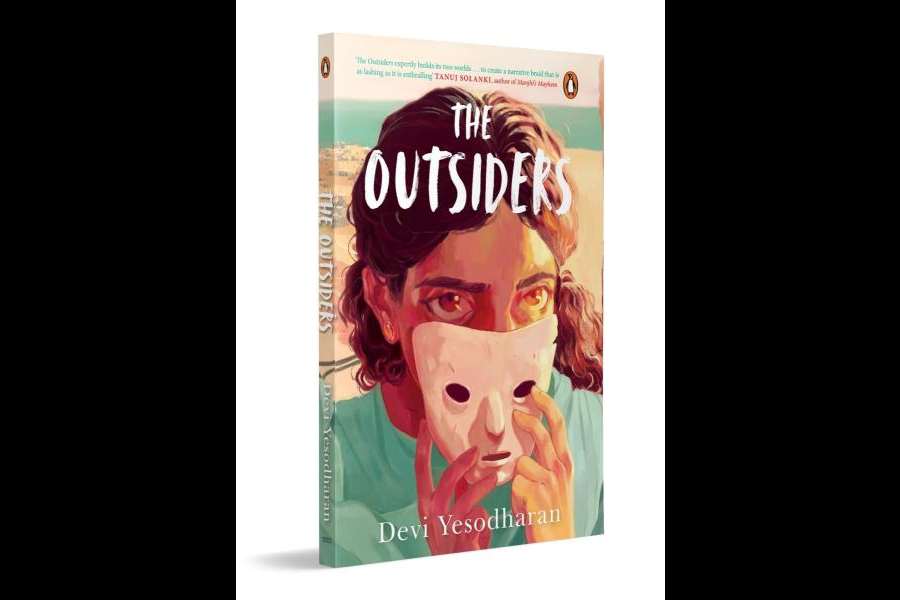

Author Devi Yasodharan

The Outsiders is your second book and follows The Empire. While the plots are different, the migrant factor in both is a meeting point for the book. What led to The Outsiders?

The Empire was based during the reign of Rajendra Chola. This time around, I wanted to write something from my experience as a migrant. Dubai in the 1990s, where I grew up, was many things — strange, utterly new, filled with people from all over hoping to make a fortune. I wanted to capture its specificity and weirdness from the migrant’s perspective.

The city was not an entirely comfortable place for a brown kid from Kerala, who found the heat unbearable, struggled with Arabic classes, and who was moved from school to school and had to make new friends every time. I felt that after all these years of living elsewhere, I would be able to make sense of it now.

I believe your stay in the Middle East helped shape the setting of the novel. How was it revisiting the place and are the characters of Saba and Rouhi inspired by anyone in particular?

I experienced the Middle East as a child and teenager. My childhood was also heavily restricted, and I was rarely allowed to go anywhere unaccompanied. So, in the afternoons there was not much to do in those days besides hang out with your friends and watch TV. I gave the cabin fever I had to Rouhi and Saba. Channel 33, which they watch, was where I got my daily hit of cartoons and TV shows: Fantastic Four, Star Trek.

Saba is a lot like a Lebanese friend I had in my third grade, who used to share her strawberry ice pops with me because I wasn’t allowed to have them. The two round circles Saba gets on her cheeks when she is excited: that’s from her. Rouhi is very much like a certain kind of Arab woman, fashionable yet conservative, with a lot of ambition that has nowhere to go due to circumstances and her early choices.

The two protagonists, Rouhi and Nita, shed their employee and employer status and connect at a level. Tell us about that.

Storytelling is a bridge, and that’s how Nita closes the distance between her employer and herself. That rather formal employer-employee relationship is made even tougher by their different backgrounds and economic class. But those differences turn out to be superficial. Rouhi is lonely and isolated in her oversized house, so that makes a friendship between her and Nita more likely. They have more in common than you expect: they are both longing for connection, they both have thwarted ambitions and they find each other in less than ideal circumstances.

You also tell a story inside a story. It gave us glimpses of The Empire. Tell us about that.

I am a big fan of ancient history. We live in a time which feels very unique: we think we are living in a great technological age but there were many times in history people felt that way. In this particular time period of the third century, new innovations in shipbuilding allowed people to cross vast distances in a fairly short time, it would have all felt very cutting edge. Sea trade was booming, and people were seeing treasures in their markets from far-off places. So it was a lot of fun to set a story in this period and experience all the newness and strangeness of it through a young hopeful protagonist.

The ‘insider’ and ‘outsider’ aspects in a foreign land have been explicitly written by you. What was your experience of growing up in Dubai like?

Dubai is now a booming city and a tourism megalopolis, but in the 1990s it was still taking shape, a half-completed vision. Like many first-generation migrants, my parents were cautious and kept to people like them, not socialising much beyond the Indian community. It’s also, once you move past the expats, a conservative city. Emiratis are family-oriented, and the immigrants and the locals move in different circles.

So my experience was very much on the outside looking in. Much of what I learned about Dubai then and later was through later visits and from the writing about the city, some very good books have been written by outsiders.

What are you working on next and how different will it be from The Empire and The Outsiders?

You know, I start books with great gusto. Then by the middle, I find myself hopelessly stuck with edits, rewrites, and research. I write myself into dead ends and have to find my way back. So every book takes more time than I think it would. The next book has a very young narrator. I’m finding that perspective hard. Wisdom usually comes late to everyone, but you so badly want your narrator to be wiser and luckier than the story allows them to be.