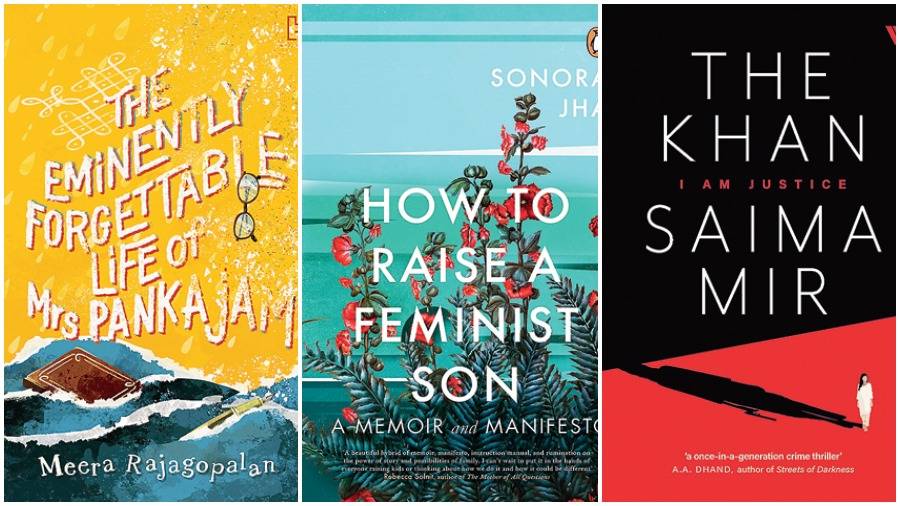

The Eminently Forgettable Life of Mrs. Pankajam by Meera Rajagopalan

That Mrs. Pankajam is forgetting her life slowly in The Eminently Forgettable Life of Mrs. Pankajam (Hachette India; Rs 399), only helped author Meera Rajagopalan to paint a picture of the protagonist in a meandering light much akin to life itself. Mrs. Pankajam is 63 years old and slowly losing her memory. As an exercise, she is advised by her neurologist to maintain a journal, one that we readers are privy to in the name of this book. Witty, sharp and sardonically humorous, our protagonist from Chennai is relatable. She is pragmatic in her approach towards life, dealing with her ailing husband Srini who is recovering from his second heart attack and two daughters Pari and Vishwa. Pari is married with two kids living in the USA, slowly falling apart from her husband Siva. She is careful with her warning when she begins documenting her life in her journal. “I imagine it will mostly comprise the menu of the day and some family gossip”, she writes. While she may not be very far from the truth, what the book offers is a peek into so many spheres of middle-class India, that the end result is a fascinating and quick read that is thoroughly enjoyable.

The novel is centred around Pari and Siva’s separation and her subsequent relationship with a woman. Mrs. Pankajam struggles to come to terms with her middle-aged daughter’s sexuality. She is the kind of person who believes in keeping people in the ambulance occupied with riddles lest they get bored as they drive her husband whose heart has attacked him, to the hospital! Even when she speaks of her daughter’s second marriage to a woman (!), she worries about Vishwa, the daughter who manages to still remain unmarried. The book is peppered with memories of the past and observations from the present that throw a different light on the protagonist. The ending of the book is starkly different from the first half of the book but it manages to tie all loose ends together, answering long-awaited questions one might have picked up along the course of reading it. A light, fun and insightful read, Meera Rajagopalan’s debut novel makes for a perfect summer companion.

How To Raise a Feminist Son: A Memoir and Manifesto by Sonora Jha

One could try to find a more relevant need of the hour than Sonora Jha’s latest book How To Raise a Feminist Son (Penguin India; Rs 399), but would probably end up failing. A single mother to a now-adult son, Jha travelled from Bombay to America succeeding and failing in various ways to raise a son who would share her feminist ideas and way of living. Dipping into her own mistakes and learnings, the professor of journalism at Seattle University writes a book that is, in no way, a simple ‘how-to’. Each chapter comes with actionable points for parents to peer into, which might often raise questions to the inherent patriarchy that is set in the minds of brown parents themselves. She refers to the Black Lives Movement and its repercussion on her mindset, recognising the importance of intersectionality in feminism.

The nuance with which Jha addresses every topic in the book provides a marvellously clear look at the sensitivity she brings and expects her readers to bring to parenting. “Go past your comfort zone and seek to be an ally and friend to LGBTQ families, to families who practise other religions or belong to other castes. Do this with a sensitivity to your own position of privilege or lack of it. Dalit feminist writer Christina Dhanaraj believes that such intimate friendships, early in childhood, are the only way forward. Don’t lay the burden on these families to share their wisdom, but thank them heartily if they do.” Not just sensitivity but also the research that went into the creation of this book demands its mandatory presence in every household. The topics that Jha covers in the book includes the importance of talking to your sons about sex, what to do when your son slips up, protecting him from the mean messaging often found in the media and protecting him from vile men who exist in society. Protecting is not shielding as one might tend to believe and can oftentimes be weathering through. She speaks of literature and art one must surround children with to help them look at the world with a keener eye. Her son Gibran was reading Tagore and Virginia Woolfe and appreciating Charulata at an age when boys discover the negatives of the Internet. The only way to perfect this imperfect world is through teachers and parents and the massive responsibility of both comes through in every line of this book. The author’s personal experiences form the perfect crux on which this book rests and we would suggest you get a copy whether you have a son or not for the world sure needs to understand their own failings when it comes to calling oneself a feminist.

The Khan: I Am Justice by Saima Mir

There is something sinister about a black text block on a book and one way to describe Saima Mir’s The Khan (Westland; Rs 499) would perhaps be ‘sinister’. The crime novel set in Bradford, England, trails the life of Jia Khan, a lawyer in London. A part of her identity she wishes to run away from is being the daughter of Pukhtan, Akbar Khan who has ruled over their community, keeping crimes at bay, by becoming a crime lord himself. Revered by the police, her father’s philosophy in life believed that one needs to commit crime to stop criminals. Disassociating herself from this narrative and her family, Jia keeps her faith in the British legal system and succeeds as a lawyer. However, it is on her father’s sudden death by murder that Jia is expected to pick up the mantle, replacing a powerful man. Not only is she shackled by her life principles but also her gender.

Jia struggles to forgive her father’s way of life to the extent of blaming him for her brother Zan’s death. It is only after taking up his role after his death does she see the side of her father that struggled with right and wrong in an effort to work for the greater good. The crime syndicate that Jia’s father was the lord of, the Jirga, rebels within to this new adjustment of Jia’s presence while little gang wars break out in the community. In the ruthless hierarchy of gender and race, white men stand at the top followed by white women and men of colour. It is only in the third rung do women of colour stand in the world. This thought is perfectly echoed in Mir’s lines “Be twice as good as men and four times as good as white men”. Interesting and convincing, this is a thrill ride that any adventure seeker would enjoy. The crisp language and even clearer ideas makes for a fantastic read.