Some matches are made in heaven; some others in publishing houses. Pairing up an author with the right illustrator can conjure up a magic that breathes life into books where words fall short. The partnership between Roald Dahl, the author arguably known best for his children’s books, and Quentin Blake, the illustrator — spanning nearly 15 years — is one such alliance, which began with Dahl’s eighth children’s novel, The Enormous Crocodile. Although Dahl was relatively new to the trade — Blake had already worked on over a hundred books — his new illustrator was rather excited about this project. It was the intellectual compatibility between the two that seems to have struck Blake: “... Roald and I met very much. In a sense, what he wrote was like what I drew in the degree of exaggeration and comedy in it. But it was a bit fiercer.”

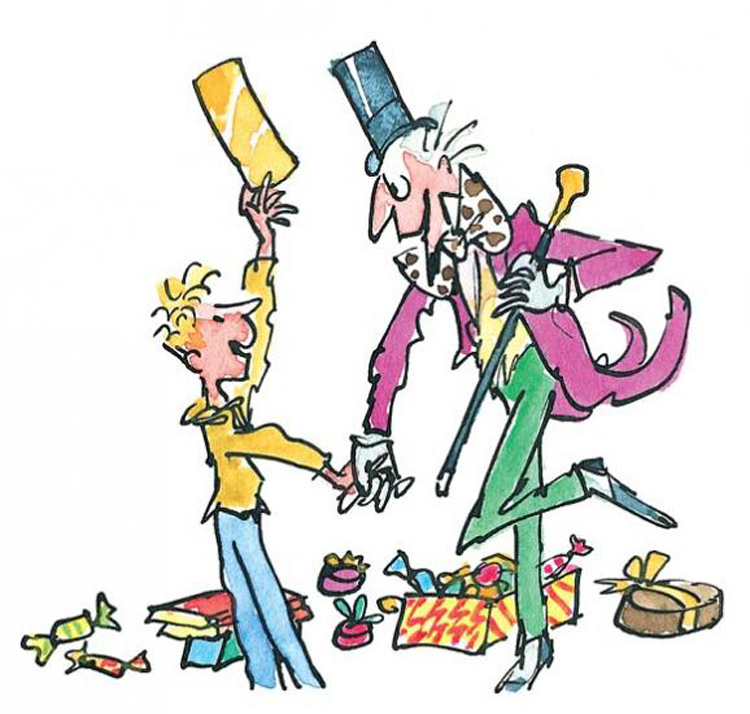

This is hardly surprising for Dahl did not completely hold back the morbidity of his short stories and adult novels from his children’s books. Whether it is The Twits, where a vicious married couple pull all kinds of deadly tricks on each other, or the retelling of Cinderella, in which the prince lops off the heads of the stepsisters, most of Dahl’s stories are pretty dark. But do Blake’s scarecrow-like figures with sharp edges and a sinister look tone down the menace in the tales or enhance it? Perhaps theirs was the right concoction; Blake’s drawings complement Dahl’s imagination in a way that is rare. This could be the reason why these illustrations stick with readers — many others have illustrated the same books — in spite of the well-received film versions of Matilda and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The point of the illustrations in the book, then, is not just to guide the young reader along the text or present a visual manifestation of the actions taking place on the page. The drawings leave space for imagination, enticing the mind to work out the unsaid and the unrepresented — the figures, after all, are made up of mere scratches and outlines, at a safe distance from reality.

Books now compete with films in terms of storytelling — a rivalry that is somewhat bizarre given the impact and potency of the new medium. Unlike the moving image, an illustration must capture the essence of a chunk of the text within a single frame. But this is where the expertise of the illustrator, often unrecognized by the lay reader, comes in. The characters in Disney’s version of A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh are based on the drawings by E.H. Shepard. The challenge was perhaps more demanding for Jonny Duddle, who, true to the textual description, retained the tall and lean Ron Weasley even after the Harry Potter films had been released, instead of modelling him on Rupert Grint, who famously played Ron on screen.

Authors and illustrators share varied relationships. J.R.R. Tolkien and the illustrator, Pauline Baynes, became friends since their first collaboration — he remarked that she “reduced [his] text to a commentary on her drawings”. But John Tenniel, who immortalized Lewis Carroll’s Alice, gave the author a tough time, at one instance convincing him to drop an entire chapter. The bond between Dahl and Blake must have run deeper. That is why 27 years after Dahl’s death — he passed away this month in 1990 — Blake illustrated The Minpins, thus leaving his name on the entire oeuvre of Dahl’s children’s literature.