The Rajasthan of literary memory usually calls up images of brave heroes, loyal vassals, gallant horses, unbreakable vows and fearlessly determined women. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many writers in Bengal, for example, were attracted to the romanticized history of medieval Rajasthan that offered stories of valour and loyalty. But the stories collected and written down by Vijaydan Detha in his Batan ri Phulwari are different; they have been told and retold by people through the ages in the Thar region. In Timeless Tales from Marwar, a short selection from the 14 volumes of Detha’s work, translated by Vishes Kothari, Detha says in an epigraph to one story that a writer’s imagination, craft and experience has limits, but the stories heard from the mouths of men and women have no limits — in storyline or collective thought process, in imagination or experience.

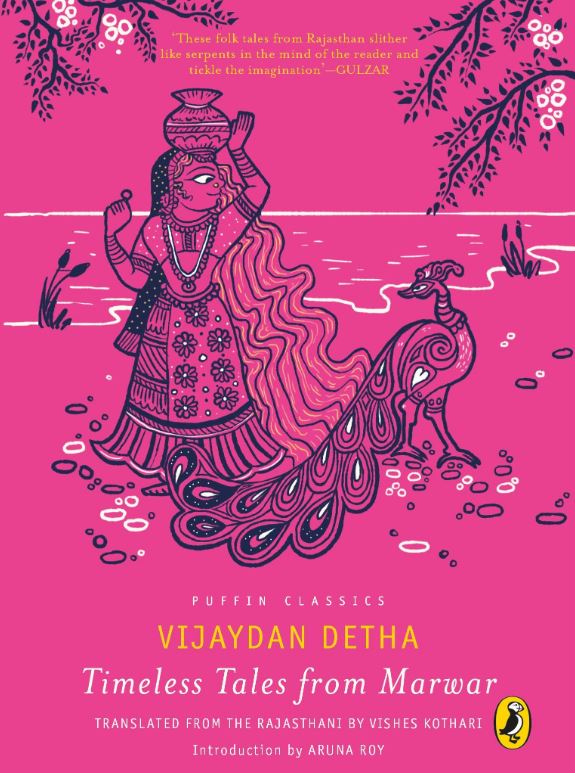

Detha is not just sensitive to the folktales full of handsome rajkanwars and demanding beauties, cruel stepmothers, wicked witches, cunning ghosts and talking animals, and of riddles, catechisms and metamorphoses, but also to the people who thought them up and kept retelling them. So while the epigraph to “Jaraav Masi’s tales” describes how Detha used to invite women to tell him stories, some others describe the person who told him the story, the teller’s region and caste. So it is not just the tales themselves, marked by Detha’s gift of storytelling, that are full of everyday people — kumbhars and seervis, the seth and the baniya — but their context too is brought alive by the design of the book. Barbers and their wives weave in and out of the text, just as they once wove in and out of homes, traditionally the repository of marvellous tales. The peacock, too, is ubiquitous, an image of colour among golden sands. So reading the book is like sitting through a storytelling session that Detha describes in another epigraph.

Folktales often seem familiar, however fantastical their world. “Eternal hope” and “The gulgula tree” both faintly recall the story of Hansel and Gretel, but they are strikingly different. In the first, hope keeps two starving infants alive when abandoned by a cruel stepmother; they drop dead when they realize their hope was misplaced. The second is a gulgula lover’s fantasy, in which a smart young man outwits a witch three times. Cleverness in folktales seldom hesitates to use deceit or violence, as “Jheentiya” also demonstrates, and the hero of “The gulgula tree” has a happy homecoming. Does Abanindranath Tagore’s Kshirer Putul have touches of “Naagan, may your line prosper”? In the form of a story-within-a story, a structure used in some other tales too, “Naagan” represents a sophisticated interweaving of wisdom, kindness, love, betrayal and forgiveness, while “The winds of time” and “The farming of pearls” present selfless goodness, “The Thakar’s ghost” insists that starvation is better than “grain of no toil” and the witty “The learning of toil” proves that true wisdom is to be found in work, not among the king’s favourite learned men. And if “The kelu tree” reminds readers of an inverted “Saat bhai champa” and a violent version of Cinderella — complete with happy ending — perhaps it is a reminder that we are all still linked mysteriously by the sea of stories.

Timeless tales from Marwar by Vijaydan Detha, Penguin, Rs 250 Amazon