Book: Lesser Lives: Stories of Domestic Servants in India

Editor: Nitin Sinha and Prabhat Kumar

Publisher: Pan Macmillan

Price: Rs 399

This thematic foray into the world of Hindi literature by two cultural historians brings together English translations of ten short stories originally written in Hindi. There is one short story representing Urdu: “Blouse” by Saadat Hasan Manto. The remaining stories come from well-established names in the field of letters in Hindi: Premchand, Jainendra Kumar, Mahadevi Varma, and Upendra Nath ‘Ashk’. The stories by relatively younger writers (compared to the Premchand era), namely, Amarkant and Shekhar Joshi, are thematically more proximate to our times and depict, quite subtly, the Janus-faced sensibilities of the emergent middle classes in the Hindi heartland.

While the editorial introduction pontificates on the rationale of the selection and brings out the semantic (and socio-political) nuances of the term ‘domestics’, one is left wondering at the inclusion of two stories each by three writers — Premchand, Rambriksha Benipuri and Mahadevi Varma. After all, the universe of Hindi literature is expansive enough to present one with the choice of making one’s selection more representative. One story per writer would have certainly avoided the current impression of editorial lassitude. Moreover, it would have offered the presumably non-Hindi reader a much more informed taste of the richness and the diversity of the Hindi literary sphere. Besides, the story “Ratnaprabha” by Jainendra Kumar does not fit the bill given the explicitly stated subtitle of the collection. This story turns out to be more about the solitude of the rich female protagonist of a joint Hindu household than about the young male servants depicted there. Also, Shekhar Joshi’s “Dajyu” is more about the general mish-mashing of class and ethnicity in an urban setting than about a domestic servant as such. No doubt, they are good stories by themselves but their inclusion here appears a bit laboured. There are some stories which are exemplars, both thematically and creatively. Rambriksha Benipuri’s “He Was a Thief” is a case in point. Mahadevi Varma’s stories are full of compassion. Premchand is at his ironical best in “Maidservant” while Amarkant’s “Bahadur” is captivating.

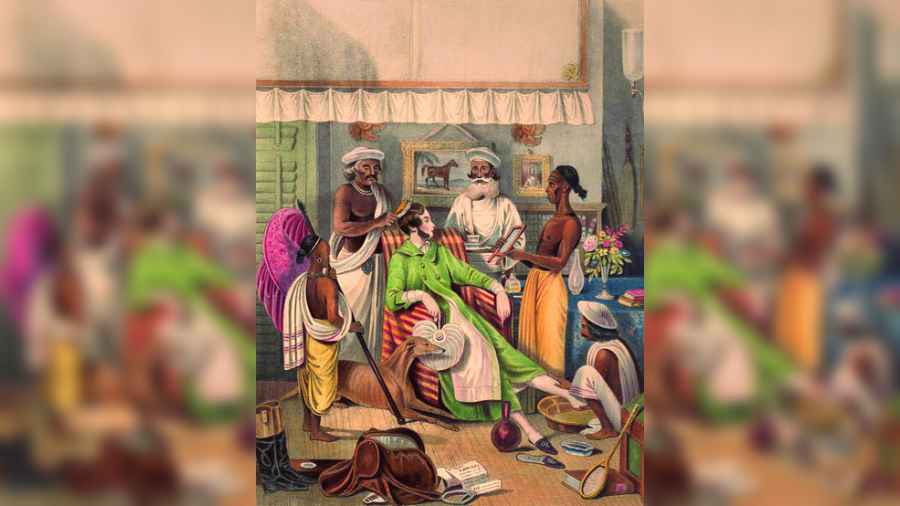

The stories presented in the book help us explore “a range of male, female and child-servant characters and their relationships with their employers in a variety of social settings: rural, zamindari, urban, middle-class, Hindu and Muslim households”. However, they are more revealing of the differing temporal sensibilities and the changing literary craft than of a unified narrative on the plight of the domestic servant whose lesser lives anchor this editorial venture. But then, these are larger questions that cannot be put at the door of the present editors. Broadly speaking, students of social sciences and history need to guard themselves against any unreflective and instrumental use of literary oeuvres even when their intentions are benign and politically correct. Literature does not lend itself easily to the regnant protocols of social scientific and historical analyses. The latter needs to carefully build bridges with literary criticism. Somehow, the global efflorescence of cultural studies has made us less cautious about the intellectual pay-offs of an empirically fine-grained and methodologically calibrated disciplinary dialogue.

This book needs to be welcomed not for what it has actually achieved between its covers but for the initiation of a healthy trend of translating Hindi originals into English for a wider audience. Somehow, unlike other Indian languages, translation of literary works from Hindi to English has picked up momentum only recently. This book indirectly adds to this significant endeavour, and, someone like me with Hindi as her/his first language will vouch for the high quality of its translations.