Breath of Gold: Hariprasad Chaurasia by Sathya Saran, Ebury, Rs 599 Amazon

In an interview for Social News, Saran elaborates on what appears to be the current opinion about biographies of classical musicians, while defending her choice of arrangement: “This book is in small segments. It keeps the pace racy and goes against the supposition that a book about a serious classical musician should be sombre and heavy.” The recent trend is to make the text approachable to the lay reader, for better outreach and, possibly, a fun-filled experience. The result is an over-fictionalization of the kind that Saran unconsciously defends: “[M]aybe TV dramas hone our expectations towards dramatic endings,” hinting as much at her own proficiency in writing television serial scripts, as in the current trend of producing a quickly consumable text, a kind of fast food of literary non-fiction. In its effort to be anecdotal, the book plays up incidents like Sharma playing a trick on Chaurasia. However, the section on Annapurna Devi feels most alive, and stands out as a great character sketch of hers plus much better anecdotal material.

Saran’s previous biographies deal with personalities from the world of films or popular music, preferably both. With Chaurasia’s life, she takes on the world of Hindustani classical music, quoting widely from a previous biography, Woodwinds of Change by Surjit Singh, and acknowledging Rajeev Chaurasia’s documentary, Romancing the Bansuri. Yet Chaurasia’s childhood and first marriage are glossed over, and his days of film music composition are highlighted more. The text uneasily conflates the image of an established classical musician who had dabbled in film music, and primarily a film music composer who later took up classical music seriously. The book credibly portrays Chaurasia as a patient, humble person full of humour; but it neither illuminates his musical journey, which readers will expect, nor provides detailed information about his life. Chaurasia’s own interview for Mumbai Mirror is consistent with his depiction in the book — all humility, peace and gratefulness. Although Saran attempts to take serendipity into account, one still feels that the hackneyed image of the struggling artist making it big should not have been the point of this book, however buttressed with celebrity forewords it may be. Overall, it is not a critical biography but a gratuitously fictionalized, sweetened account of the life of an artist.

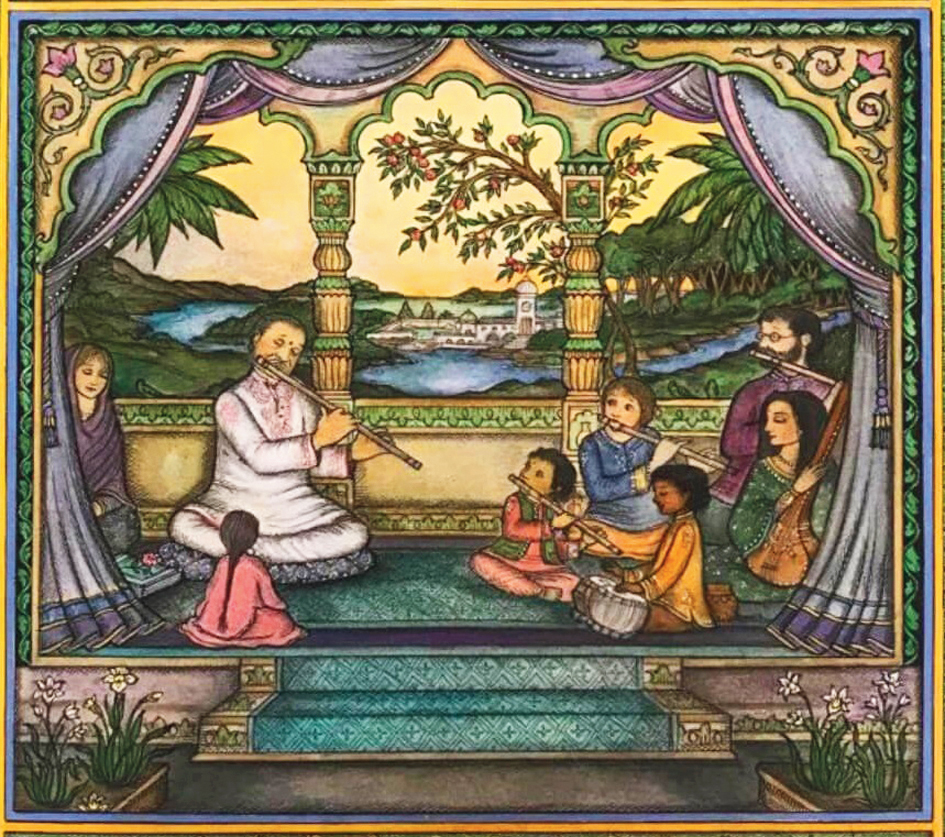

“Wrestler in the morning, student during the daytime and flute player in secret” is how the blurb of Sathya Saran’s Breath of Gold sums up Hariprasad Chaurasia’s pre-professional life. Expected to follow in his wrestler father’s footsteps, Chaurasia had nonetheless long broken secretly away from that life. He married twice, relocated to Bombay, met Shivkumar Sharma, and together they forayed into film music. He retraced his steps to learn from the surbahar maestro, Annapurna Devi, went on to play with George Harrison of The Beatles, founded a gurukul, and taught at the Rotterdam Music Conservatory. Yet an eventful life may not necessarily be dramatic, and that is where Saran’s biographical narrative falls short, constantly hunting for spectacle where there seems to be little or none.

The book is heavy to the eye but sits lightly in the hand in spite of its hardbound bulk. The indifferent jacket has a file photo of Chaurasia playing the flute, taking up exactly as much space as his name, the author’s name, and the title. Inside, non-chronologically ordered text segments and their sudden changes of font are somewhat jarring. Several tiny inaccuracies mar the text. Umrao Jaan was released in 1981, Sharma’s biographer is called Ina Puri, Subhash Ghai could not have heard Chaurasia on a CD, Bengali women wear iron bangles on the left wrist, and so on.