These are fraught times. Interestingly, the Constitution has become a powerful emblem of protest. Perceived as the ultimate saviour, “We, the people of India” have embraced it in a remarkable show of political acuity and vowed not to accept the abrogation of its core guiding spirit.

It also appears quite the perfect setting for a gripping flashback on the lead-up to azaadi in 1947 and the tumultuous, eventful decades thereafter.

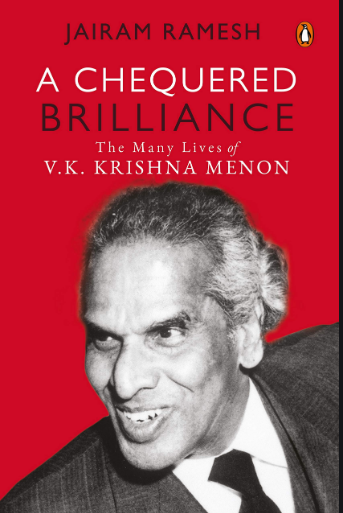

V.K. Krishna Menon, the protagonist in Jairam Ramesh’s latest meticulously researched offering to biography buffs and cognoscenti of various stripes, was undeniably one of the icons who made the idea of India come alive, on the national and international screens. Walt Whitman’s famous line, “I am large, I contain multitudes”, suits him. As Lord Mountbatten presciently remarked in 1956, “You will certainly have a great place in history when it comes to be finally written.”

Given this enviable branding, it is only to be expected that there will always remain a magnetic pull to delve deeper and mine more extensively his fascinating, compellingly inspirational life and times, in spite of tomes already being available in the public domain. What we now have from Ramesh are 700-plus pages of fine print and photographs, which reportedly took only 15 months to put together, end to end.

The stylistic curating of the book is its primary differentiator, in what may arguably be described as a fairly jam-packed Krishna Menon genre. It is positioned as more of an epistolary novel, in the words of the legend himself and those of his contemporaries, as he evolved, as he achieved, as he stumbled, with the author being consciously non-judgmental, playing the empathetic sutradhar’s part with finesse, resisting the temptation of indulging in ‘psychohistory’. The other noteworthy differentiator relates to his donning a savvy aggregator’s mantle, pointing to substantial new source materials which have become available fairly recently in archives in different countries, including India, the United States of America, the United Kingdom, Canada, Sweden, Russia, France, China and Australia. He has mined but minimal amounts. They await the fancy and time of avid researchers, crafted in Ramesh’s indefatigable mould.

What is provided to the reader is a block chain of intricate facts, cutting through the clutter of folklore, both positive and negative. Overarching it all is the ardent hope that the man who is now remembered only for the debacle of 1962 or for his histrionics at the United Nations will come through as one among the most formidably intellectual men of his generation, with stellar achievements, straddling a mind-boggling canvas.

The hope has, by and large, not been belied and the book does ample justice to one of our most compelling, consequential and controversial political figures, referred to at various times as Rasputin, Mephistopheles, Lucifer, Svengali, Evil Genius, The World’s Most Hated Diplomat, Sombre Porcupine, The Formula Man, along with many delightful epithets.

The eloquently sensitive portrayal of Krishna Menon is that of a super-charged, brilliant ascetic, living on nothing but tea and buns. Although tormented by debilitating physical and psychological challenges, he did not let them get the better of him. For almost two decades in the 1930s and 40s, he was singularly responsible for creating and sustaining a climate of opinion in favour of Indian Independence in politically significant sections of British society. He initiated the idea of a Constituent Assembly with his mentor at the London School of Economics, Harold Laski, even sending in a draft Constitution, and went on to play a key role in the transfer-of-power negotiations, in close concert with Lord Mountbatten and Jawaharlal Nehru, as their valued sounding board, in the months leading up to the dismantling of imperial power. Having ensured that India continued in the Commonwealth, between 1947 and 1950, he was a high commissioner with impact in London, in spite of being stung hard by the audit-generated Jeep scandal, which refused to go away for a protracted nine-year period. The unforgettably forceful interventions on Kashmir at the UN are, till today, recalled with tremendous admiration. At the height of the Cold War, Krishna Menon helped unravel many complex problems, cutting across continents, and fittingly received unreserved global acclaim from the highest echelons.

A Chequered Brilliance: The Many Lives of V.K. Krishna Menon By Jairam Ramesh, Penguin, Rs 999 Amazon

So far so good. Of course, the reader is called upon to have humongous patience and rare agility while going through the quotable quotes from heaps of reports, despatches, intelligence briefs, books and, most importantly, mails, ranging deliriously from the knowledgeable and preachy to the maudlin and suicidal. Having successfully navigated through it all, with one’s processing powers intact, the ultimate value-add lies in the refined detailing and consequential insight-accretion. Although the book is somewhat heavy and apparently disjointed at places, with the narrator and the narration colliding and jostling for attention and it has a few jarring typos, these do not make the cut to justify any exasperated cribs. They should, in fairness, be put down to the familiar problem of plenty, especially in the info-world.

However, where there appears a misstep, certainly unintended, it is in achieving a convincing rebalancing in the endless blame-game centring around the India-China conflict spanning 1959-62. As far as public memory goes, this was indisputably one of the darkest phases of the country’s contemporary history. The author wanted very much to have Krishna Menon acknowledged and accepted as a towering leader whose legacy did not deserve to be permanently disfigured by this searing indictment.

This misstep may have happened because of the rigid chronology-format compulsion which has framed and — in a sense — bound down the book. References to the dramatis personae of this conflict keep surfacing in various chapters in Part V of the book at different time points, admittedly in different contexts, without really illuminating its mangled discourse. The inherited antipathy may well continue to cast its dark shadow, putting paid to the strenuous efforts of the author.

During the 17 years that he was prime minister, the only person with whom Nehru shared uninhibited intellectual camaraderie was Krishna Menon. His induction into the Union cabinet as defence minister had everything to do with this much-misunderstood bond. Unfortunately, here he performed the worst and was forced to exit. Nehru could not keep him back in spite of his stolid support.

The China imbroglio continues to be a drag, the fingers having written and moved on.